Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With HIV Infection and AIDS

HIV Infection and AIDS: Transmission to Health Care Providers

Transmission

to Health Care Providers

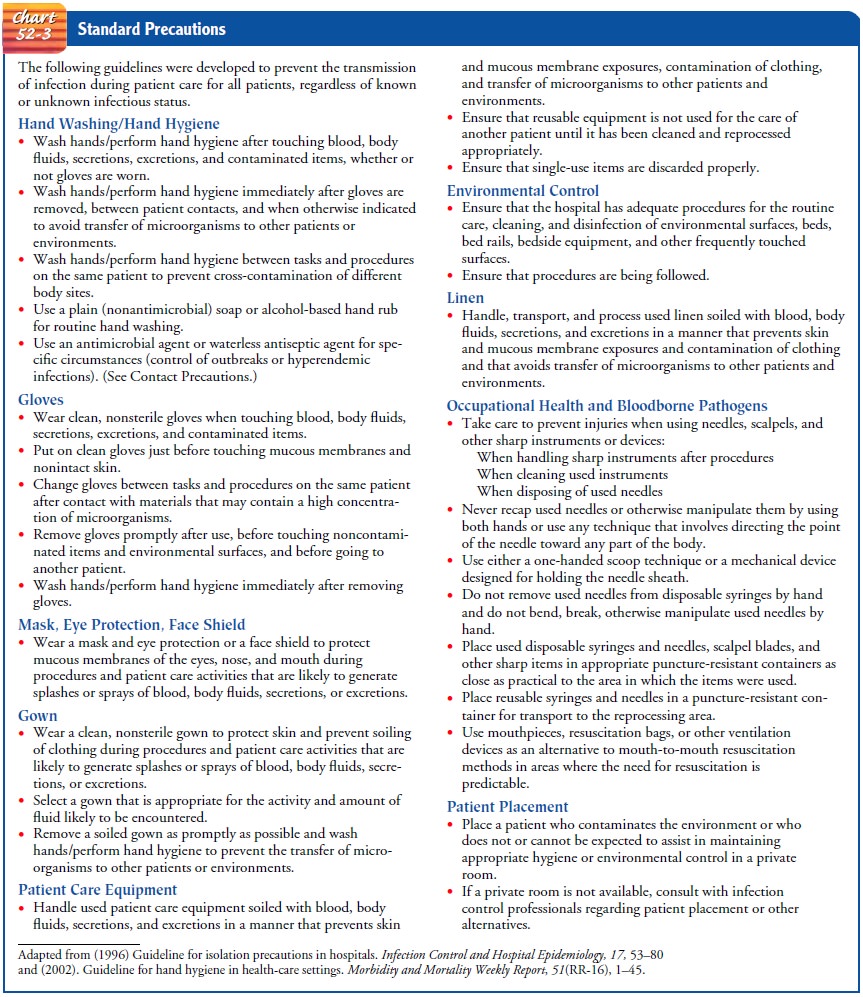

STANDARD PRECAUTIONS

In

1996, efforts were made by the CDC and its Hospital Infec-tion Control

Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) to stan dardize procedures and reduce the

risk for exposure through de-velopment of Standard Precautions. Standard

Precautions in-corporate the major features of Universal Precautions (designed

to reduce the risk of transmission of blood-borne pathogens) and Body Substance

Isolation (designed to reduce the risk of transmission of pathogens from moist

body substances); they are applied to all patients receiving care in hospitals

regardless of their diagnosis or presumed infectious status (Chart 52-3).

Standard Precautions apply to blood; all body fluids, secre-tions, and

excretions, except sweat, regardless of whether they contain visible blood;

nonintact skin; and mucous membranes (Hospital Infection Control Practices

Advisory Committee [HICPAC], 1996).

The primary goal of Standard Precautions is

to prevent the transmission of nosocomial infection. The first tier, referred

to as Standard Precautions, was developed to reduce the risk for all

rec-ognized or unrecognized sources of infections in hospitals. A sec-ond tier

for infection control precautions for specified conditions, called

Transmission-Based Precautions, was designed for use in addition to Standard

Precautions for patients with documented or suspected infections involving

highly transmissible pathogens. The three types of Transmission-Based

Precautions are referred to as Airborne Precautions, Droplet Precautions, and Contact

Precautions. They can be used singularly or in combination, but they are always

to be used in addition to Standard Precautions (HICPAC, 1997).

Large-scale studies of exposed health care

workers continue to be conducted by the CDC and other groups. In November 2000,

the Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act became law, mandat-ing health care

facilities to use devices to protect against sharps injuries (Worthington,

2001).

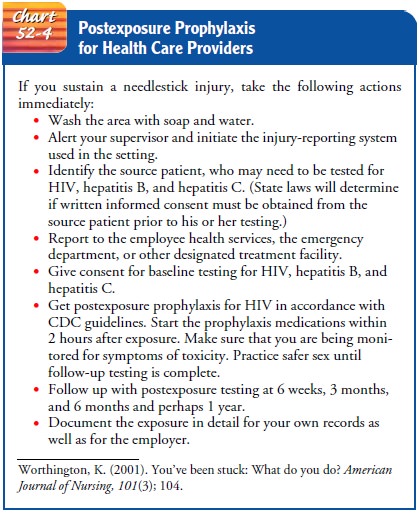

POSTEXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS FOR HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS

Postexposure

prophylaxis in response to exposure of health care personnel to blood or other

body fluids has been proven to reduce the risk for HIV infection (Worthington,

2001). The CDC (1998) recommends that all health care providers who have

sus-tained a significant exposure to HIV be counseled and offered anti-HIV

postexposure prophylaxis, if appropriate. Some clini-cians are considering

using postexposure prophylaxis for patients exposed to HIV from high-risk

sexual behavior or possible con-tact through injection drug use. This use of

postexposure pro-phylaxis is controversial because of concern that it may be

substituted for safer sex practices and safer injection drug use. Postexposure

prophylaxis should not be considered an acceptable method of preventing HIV

infection.

The medications recommended for postexposure

prophylaxis are those used to treat established HIV infection. Ideally,

pro-phylaxis needs to start immediately after exposure; therapy started more

than 72 hours after exposure is thought to offer no benefit.

The recommended course of therapy involves taking the pre-scribed mediations for 4 weeks. Those who choose postexposure prophylaxis must be prepared for the side effects of the medica-tions and must be willing to face the unknown long-term risks, because HIV often becomes resistant to the medications used to treat it. If the person becomes infected despite prophylaxis, viral drug resistance may reduce future treatment options. The cost is also of concern; the cost of a drug regimen ranges from $500 to more than $1,000, plus the costs of testing and counseling. Health insurance generally does not cover the costs of medica-tions, laboratory tests, and counseling (Chart 52-4).

Related Topics