Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: A Psychiatric Perspective on Human Development

Theories and Models of Development

Theories and Models of Development

Theories of Development

Theories are important to the study of development

for a number of reasons. They organize and prioritize large amounts of data

regarding infant development, indicating which are the most sa-lient and why.

Often, they also explain the importance of the early years for subsequent

development, indicating how developmen-tal issues are related to broader issues

of the lifespan. Generally, they move beyond mere descriptions of behavior and

attempt to explain why individuals are motivated to behave in certain ways at

certain times. Finally, they may generate meaningful and test-able hypotheses

for empirical research.

On the other hand, theories have inherent

liabilities. A selective focus on one theory may obscure others of equal or

greater value. Theories also inevitably lead to oversimplification of complex

processes and events. They may create biases that af-fect how we interpret

observations and how we make inferences from these observations. The history of

psychology is filled with examples of adherence to a particular point of view,

making it impossible to see disconfirming information. All of these factors

warrant caution about the uncritical use of theories to understand development.

A useful theory is one which is developmental, in-tegrative, contextualist,

constructionist and perspectivist in na-ture, discounting its own absolute

claim to truth and integrating as many relevant approaches as possible. An

integrative devel-opmental theory accounts for the dynamic interactions of

biol-ogy (including neuroanatomy, genetics, neurotransmitters, etc.),

relationships (including parental, sibling, peer and wider social

groups), culture (including cultural norms for

individual and col-lective development), and technology (including medication,

in-formatics, etc.) (Wilber, 2000).

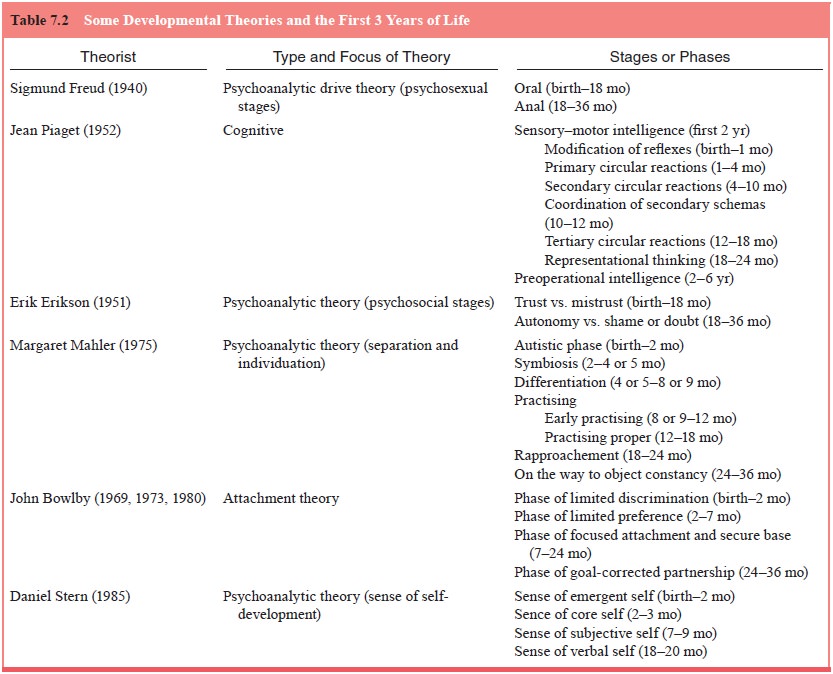

Table 7.2 presents a brief summary of some of the

major theories of development as they pertain to the first 3 years of life.

Although others could have been selected, those presented have been most

influential with regard to clinical practice and research on early development.

As noted in Table 7.2, the theories vary with regard to their particular focus

of development, although most use stages to describe periods of discontinuity.

There has been a scientific preoccupation with

defining the relative contributions of genetic endowment and environmental

experience on the course of human development. While early be-havioralists took

the extreme view that children can be shaped al-most exclusively by their

environments, today evidence supports the view that genes and experience

interact continuously overtime in a transactional manner that leads to the

unique develop-ment of an individual. The study of environmental contributions

has steadily improved through the application of more careful methods of

assessment and an appreciation of the value of exam-ining the many components

of the early experience of children.

However, the most explosive advances in the

understand-ing of human development have been made as specific gene sequences

have been identified and linked to physical and be-havioral outcomes. In the

past decade, the pace of new gene discovery has increased exponentially as a

consequence of the success of the Human Genome Project. It is now estimated

that human beings have approximately 38 000 to 40 000 genes. Deter-mining the

precise number has been elusive as it has been neces-sary gradually to

understand that human genes are more complex than the genes of simpler

organisms. Specifically, many human genes produce multiple proteins. We are now

learning about the degrees of genomic variability that exist between

individuals, as well as beginning to understand how genes interact with each

other and how they are regulated by the environment. A key fo-cus of new

research is the discovery of how the passage of time and the gradual maturation

of the individual affect the expression of genes that have remained silent but

potentially ominous from the beginning of fetal development. Future studies of

cohorts of infants who are at known genetic risk for a trait or illness maywell

identify environmental factors associated with both the ex-pression and the

suppression of gene expression.

The concept of studying development longitudinally

has its origin in the studies of lives and was well established by Plu-tarch

and popularized by Shakespeare. In many ways, biogra-phers strive to examine

the origins of adult traits through consid-eration of the early experiences of

their particular subject. This tradition was adopted by psychoanalysts who

searched for the origins of psychopathology through the exposition of a

“genetic formulation’’. The choice of the word “genetic’’ to modify a

con-ceptual formulation based on the experience of the individual is somewhat

ironic. The term has largely been abandoned, as these formulations had little

to do with the function of individual genes. Nonetheless, this focus on the

influence of early experi-ence on development may well have been a

foreshadowing of the importance of intense early experience on gene expression.

In all likelihood, the genetic formulations of the future will focus on how

experience regulates gene expression at the molecular level.

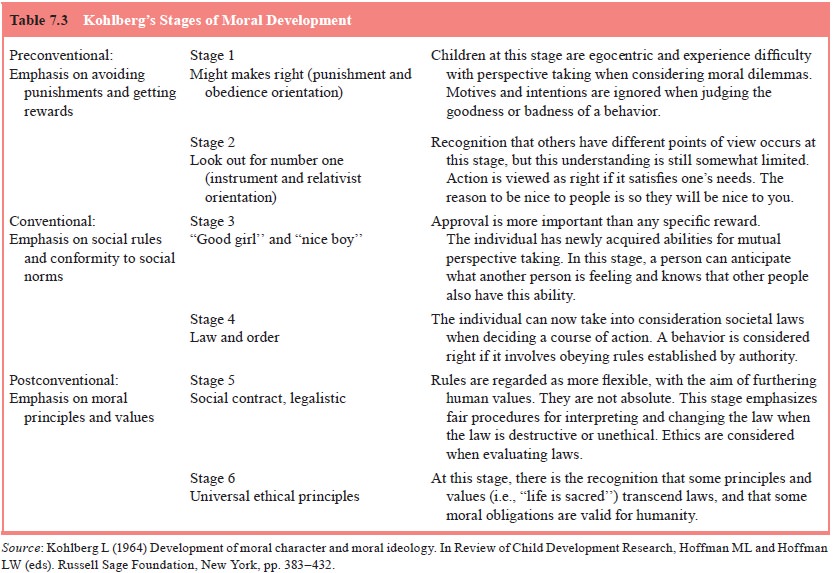

The concept of parallel yet interacting lines of

develop-ment was popularized by Anna Freud (1946) who created a classical

monograph that articulated nine lines of development that were well described

through adolescence. Although some of these conceptual lines have been

abandoned, the overarching principle of a line of development has proven to

have heuristic value. Table 7.3 lists four relevant developmental lines.

Other psychoanalysts have built on her model to

create parallel lines extending into adulthood. Erikson (1963) further

elaborated the evolution of domains of function in the creation of his

epigenetic stage model, as presented in Figure 7.1. His para-digm continues to

have a strong influence on psychiatric theory.

as is wellillustrated by Vaillant’s work who has

extended the Eriksonian model by proposing two additional phases of the adult

life-cycle, career-consolidation vs. self-absorption and keeper of the meaning

vs. rigidity. The former acknowledges the importance of achieving a stable

career identity in addition to the achievement of identity within one’s family

of origin. The latter describes fur-ther Erikson’s concept of generativity

beyond assuming sustained responsibility for building the community and for the

growth, well-being and leadership of others. “Keeper of the meaning’’ and its

virtue, wisdom, involve a nonpartisan and less personal approach to others and

is to be distinguished from the tasks of a generative coach, partisan parent,

or mentor from the tasks of a Supreme Court judge or chair of a historical

society.

Although lines of development are attractive

conceptually, they are a deceptively simplistic representation of the complex

evolution of personality. The concept of “decalage’’ was put for-ward by Piaget

(1952) to refer to a disengagement in the normal evolution of the parallel

development of specific cognitive abili-ties. However, decalage is equally

salient in the conceptualiza-tion of major distortions in emotional or social

development.

Related Topics