Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: A Psychiatric Perspective on Human Development

Cognitive Developmen

Cognitive Developmen

The study of cognitive development provides a

perspective on the evolution of the capacity to think. Increased cognitive

abili-ties are an integral component required for the onset of language.

Changes in thinking ultimately shape the course of emotional, social and moral

development. Recent investigations of the re-lation of brain development to

cognitive development have at-tempted to attribute specific developmental

changes in central nervous system function with the achievement of new

cognitive abilities (Casey et al.,

2000; Anderson, 2001).

However, the acquisition of mental abilities has

been charted as an independent sequence of mental accomplishments. Piaget

es-tablished the field of cognitive development, and his stage theory of the

evolution of cognitive processes has dominated this field (Piaget and Inhelder,

1969). Although specific aspects of his four primary stages have been modified

by subsequent empirical experi-ments as well as by the development of a greater

appreciation of the role of emotions and context in the utilization of

cognitive abilities, his careful observations and brilliant deductions have

provided the framework on which much of our knowledge of cognitive develop-ment

has been built. In contrast, Vygotsky (1978) provided a model of early

cognitive development that placed greater importance on the influence of

culture and language-mediated guidance by adults

Piaget introduced the concept of “schemas’’ which

he defi ned as units of cognition. He further described processes that result

in schema modifi cation, which begin in infancy as a child assimilates new

information and accommodates to novel stimuli. A particularly important

Piagetian concept has been that of a decalage within cognitive development,

which refers to an unevenness in cognitive development. For example, a child

may demonstrate cognitive abilities at the concrete operational stage of development with regard to conservation of

volume and at the same time retain preoperational forms of thinking such as

per-sistent egocentrism. Such an unevenness can also be seen across lines of

development.

Even newborns have the ability to learn through

making associations between different states or experiences. There is evidence

that cognitive “prewiring’’ exists, which allows for the perceptual capacities

of infants that are necessary to seek stimu-lation and interaction with adult

caregivers. A key capacity re-quired for these early cognitions is recognition

of the invariant features of perceptual stimuli coupled with the ability to

translate these invariant features across sensory modalities. Interestingly,

infants can differentiate the human voice from other sounds in-nately without

“learning’’ the complex characteristics of the structure and pitch of speech.

By 2 to 3 weeks of age, cross-modal fluency is

demon-strated by the ability of infants to imitate facial expression. This

requires the recognition of a visual schema of a facial expression to be linked

with a proprioceptive tactile schema of producing a facial expression. By 3

months of age, infants can be classically conditioned, and their interest in

stimuli led Piaget to suggest this was a period dominated by attempts to make

“interesting spectacles last’’ (Piaget and Inhelder, 1969).

By 6 months of age, associations between “means’’

and “ends’’ have been demonstrated. This is followed by object per-manence,

which evolves during the second half of the first year. During the second year,

infants can infer cause after observing an effect as well as anticipate effects

after producing a causal action. A corollary of this new ability is that they

are now able correctly to sequence past events.

By the third year of life, children enter the

preoperational stage. This form of thinking is more similar to adult cognition,

but it incorporates magical explanations and is marked by a tendency to focus

on one perceptual attribute at a time (centra-tion). Idiosyncratic cosmological

theories are common and are usually dominated by transductive reasoning, which

attributes causality based exclusively on temporal or spatial juxtaposition.

Throughout the preschool period, attention span and memory are limited while

pretend play and fanciful thinking are common. Animism is frequently used and

refers to endowing inanimate objects with the qualities of living things. Not

surprisingly, chil-dren having imaginary friends and talking pets characterize

this cognitive period. The preoperational stage is also the time dur-ing which

explosive language development occurs. This develop-ment appears to be made

possible by a genetically determined capacity for language. However, language

development is clearly enhanced by experiential support and parental

communication that is sensitive to the child’s ability to process new words and

grammatical structure.

By age 6 or 7 years, children begin to use

operational think-ing. The child who has attained concrete operational thought has

the ability to conserve both volume and quantity as well as being able to

appreciate the reversibility of events and ideas. A shift from an egocentric

perspective results in a new capacity to appre-ciate the perspective of others.

These new cognitive skills dem-onstrate an ability to engage in logical

dialogue and to develop an appreciation of more complex causal sequences. These

new cognitive abilities are clearly required for a child to benefit from the

grade school curriculum.

Adolescence results in the development of a new

processing capacity that involves the manipulation of ideas and

conceptsFurthermore, the informational fund of knowledge is dramatically

expanded and serves as a referent for verification of new data that are

assimilated. A final major transition is possible with the development of the

ability to reflect on cognition as a process. This is referred to as the

development of a metacognitive capacity. Achievement of this capacity allows

adolescents to understand and empathize with the divergent perspectives of

others to a greater degree than was previously possible. This capacity is

necessary for recursive thinking which involves an awareness that others can

think about the domain of the adolescent’s own thought. These cognitive skills represent

the transition into the final stage of cognitive ability, which is referred to

as the use of formal operations. One capacity characteristic of this stage is

the ability to understand complex combinatorial systems that require a well-developed

sense of reversibilities that include inversion, reciprocity and symmetry. New

levels of problem solving are achieved that include the ability to recognize a

core problem or core isomorph within a more complex new problem. The adult with

formal operational ability can recognize a previously successful solution and

use this knowledge to develop a parallel innovative solution to the complex

problem. It is important to appreciate that many adults remain at the stage of

concrete operations and never develop these more advanced capacities.

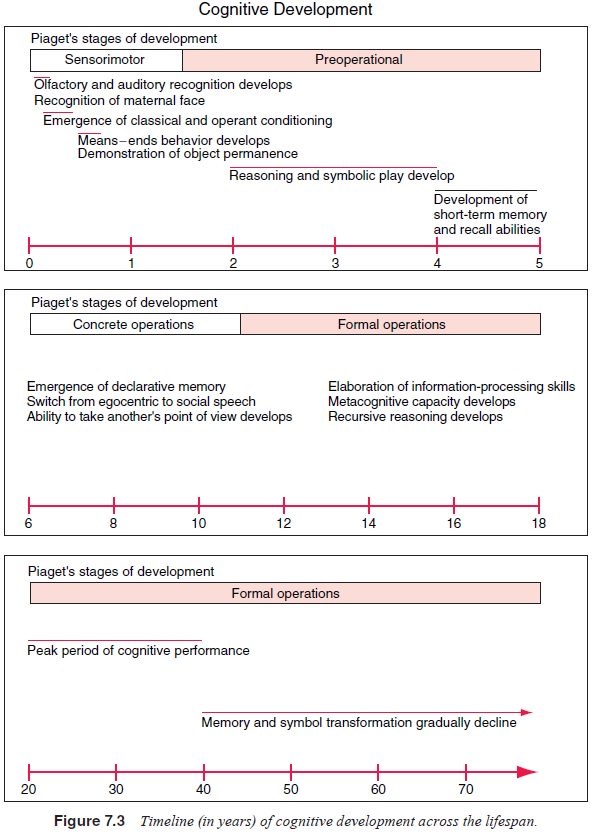

A timeline of cognitive development during the

course of the lifespan is presented in Figure 7.3.

Related Topics