Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: A Psychiatric Perspective on Human Development

Social Development

Social Development

It has become widely appreciated that infants are

socially interactive from the first days of life. The strong tie that parents

feel for their infants has been referred to as the parent–infant bond. Between

7 and 9 months of age, infants develop separation protest and a negative reaction

to the approach of a stranger. During the second half of the first year, the

attachment of the infant to his or her parents evolves. The primary role of the

attachment figure is the provision of a secure base from which the infant can

begin to explore a wider social environment (Ainsworth et al., 1978). It is within the context of the attachment

relationship that the first Eriksonian state of “basic trust’’ is achieved.

Attachment is the affectional connection that a

baby de-velops with its primary caregiver, most often the mothering person,

which becomes increasingly discriminating and enduring. It is the availability

and responsiveness of the mother or other caretaker that is ultimately the most

influential in determining the strength and safety of the attachment system.

The infant’s attachment behavior is an attempt to bring stability,

predict-ability and consistency to his or her world through drawing the mother

closer. There is an extensive literature on and theories about what occurs in

the mental life of infants and children dur-ing the attachment process. At the

risk of over-simplifying, the most intriguing and clinically useful of these

theories focuses on the process of internalization. Internalization is the

mechanism for building psychological structure. More specifically, it is an

attempt to describe how the child achieves an increasingly stable and

sophisticated view of himself and the world around him. The acquisition of

internal representations of the infant and those who care for him are the

building blocks of identity formation and in-dividuation. The former includes

the capacity for relatedness and cohesiveness of self and the latter refers to

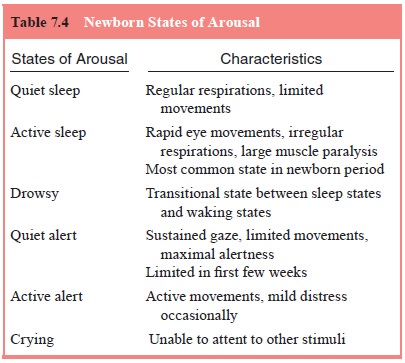

the establishment of autonomy or separateness. Table 7.4 summarizes patterns of

at-tachment. There is an extensive literature on attachment patterns and

subsequent development of psychopathology (Kay, 2005).

By 18 months, play begins to be more directed toward peers, but this does not become the predominant form of play until the third year. Along with the striving toward autonomy that characterizes Erikson’s second stage, there emerge more negative affective interactions within the context of the attachment relationship. This phenomenon is widely recognized within the popular culture as the arrival of the “terrible twos’’. However, the quality of the attachment relationship earlier in life has been shown to predict better preschool social adaptation and a stronger sense of self-worth. Included in it is the observation that patterns of social dominance become established during the third year of life and that insecurely attached preschoolers exhibit more conflict and aggression in the establishment of their social status. These early social strivings are compatible with Erikson’s third stage, which has as its central developmental objective the achievement of initiative within the context of potential failure and guilt.

Gender differences emerge by 2 years of age. Boys

are more aggressive and tend to play with toys that can be manipu-lated. Girls

prefer doll play and artwork. However, boys and girls also engage in both types

of play. By the end of the third year, gender preference in play has emerged,

and the preference is to play with children of the same sex. This preference

remains throughout childhood. Associative play, which refers to play that

involves other children and the sharing of toys but does not include the

adopting of roles or working toward a common goal, becomes more prominent

during the preschool years. Coopera-tive play also emerges along with a strong

tendency to include elements of pretend play into the cooperative sequences.

The cul-tural context begins to shape the nature of social interaction even at

these earliest stages of development.

During the school years, the role of peers in

shaping so-cial behavior becomes predominant. Small groups form, and the

concept of clubs becomes important. Shared activities, including the collection

of baseball cards or doll clothes, are a common

and important characteristic of this period.

Sharing secrets and making shared rules also serve as organizing social

parameters. Social humor develops, and appearance and clothing become an

important social signaling system. It is a time of practicing and developing athletic,

artistic and social skills that are associated with Erikson’s fourth stage of

achievement of industry within the context of a sense of potential

interpersonal inferiority.

In adolescence and throughout the adult years,

social and sexual relationships play a complex and powerful role in shap-ing

experience. With the onset of strong sexual impulses and in-creasing academic

and social demands in adolescence, the role of peer influences in shaping both

prosocial and deviant behav-ior becomes powerful. Adolescence is the period

during which Erikson described the central objective to be the establishment of

an individual identity, and there has been wide acceptance of this sense of

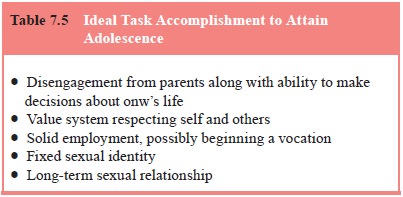

self-occurring within the context of the social and cul-tural experience. Table

7.5 describes the tasks of adolescence.

The roles of adulthood are complex and focused on

the most basic issues of marriage, parenting, working and dealing with death.

The key to understanding the sequential nature of adult development lies in the

appreciation of both the relative complexity and the inner threat of the tasks

and commitments that must be mastered. The twin anxieties of young adulthood

involve the abilities to commit to one person and one job without sacrificing

autonomy. Prospective studies suggest that by midlife a major developmental

task for women is to achieve traits of in-dependence, rationality and

self-direction. Similarly it becomes equally enriching for men in midlife to

achieve warmth, emo-tional expressiveness and relatedness (Vallant, 1977;

Gutttman, 1977). Individuals who achieve generativity almost always have

evolved to stages of identity formation, achievement of intimacy and career

consolidation. It is important to note that within the various Eriksonian

stages, a selfless generativity reflects a clear capacity to care for and guide

the next generation. The final stage of adult development, achieving integrity,

may be compared to putting a garden to bed for the winter. Reflection on one’s

life facilitates coming to terms with it and accepting the past.

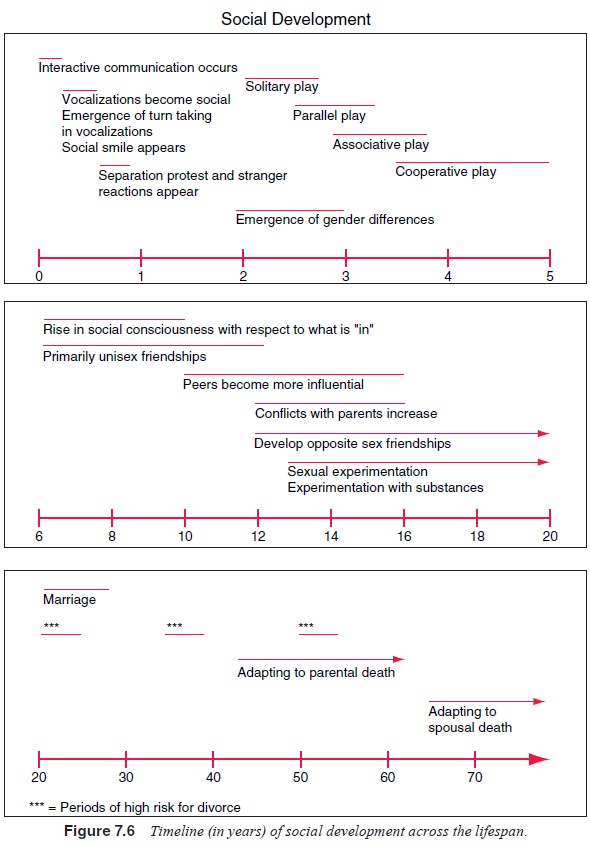

A timeline of social development during the course

of the lifespan is presented in Figure 7.6.

Related Topics