Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Shock and Multisystem Failure

Stages of Shock

Stages of Shock

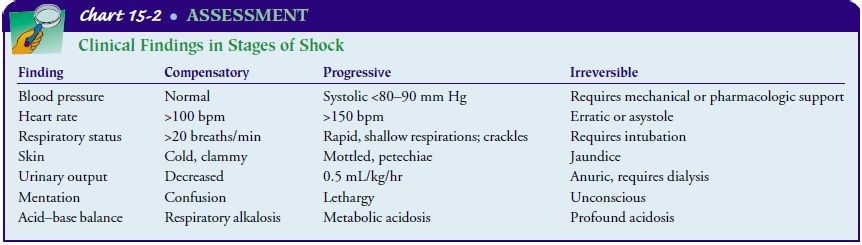

Some think of the shock syndrome as a continuum along which the patient struggles to survive. A convenient way to understand the physiologic responses and subsequent clinical signs and symp-toms is to divide the continuum into separate stages: compen-satory, progressive, and irreversible. (Although some authorities identify an initial stage of shock, changes attributed to this stage occur at the cellular level and are generally not detectable clini-cally.) The earlier that medical management and nursing inter-ventions can be initiated along this continuum, the greater the patient’s chance of survival.

COMPENSATORY STAGE

In the compensatory stage of shock, the patient’s blood pressure remains

within normal limits. Vasoconstriction, increased heart rate, and increased

contractility of the heart contribute to main-taining adequate cardiac output.

This results from stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system and subsequent

release of cate-cholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine). The patient

dis-plays the often-described “fight or flight” response. The body shunts blood

from organs such as the skin, kidneys, and gas-trointestinal tract to the brain

and heart to ensure adequate blood supply to these vital organs. As a result,

the patient’s skin is cold and clammy, bowel sounds are hypoactive, and urine

output de-creases in response to the release of aldosterone and ADH.

Clinical Manifestations

Despite a normal blood pressure, the patient shows numerous clinical

signs indicating inadequate organ perfusion (Chart 15-2). The result of

inadequate perfusion is anaerobic metabolism and a buildup of lactic acid,

producing metabolic acidosis. The respira-tory rate increases in response to

metabolic acidosis. This rapid res-piratory rate facilitates removal of excess

carbon dioxide but raises the blood pH and often causes a compensatory

respiratory alkalo-sis. The alkalotic state causes mental status changes, such

as con-fusion or combativeness, as well as arteriolar dilation. If treatment

begins in this stage of shock, the prognosis for the patient is good.

Medical Management

Medical treatment is directed toward identifying the cause of the shock,

correcting the underlying disorder so that shock does not progress, and

supporting those physiologic processes that thus far have responded

successfully to the threat. Because compensation cannot be effectively

maintained indefinitely, measures such as fluid replacement and medication

therapy must be initiated to maintain an adequate blood pressure and reestablish

and main-tain adequate tissue perfusion.

Nursing Management

Early intervention along the continuum of shock is the key to im-proving

the patient’s prognosis. Therefore, the nurse needs to as-sess systematically

those patients at risk for shock to recognize the subtle clinical signs of the

compensatory stage before the patient’s blood pressure drops.

MONITORING TISSUE PERFUSION

In assessing tissue perfusion, the nurse observes for changes in level

of consciousness, vital signs (including pulse pressure), urinary output, skin,

and laboratory values. In the compensatory stage of shock, serum sodium and

blood glucose levels are elevated in re-sponse to the release of aldosterone

and catecholamines.

The role of the nurse at the compensatory stage of shock is to monitor

the patient’s hemodynamic status and promptly report deviations to the

physician, assist in identifying and treating the underlying disorder by

continuous in-depth assessment of the pa-tient, administer prescribed fluids

and medications, and promote patient safety. Vital signs are key indicators of

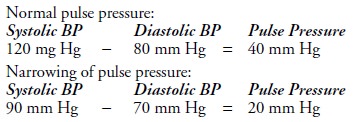

the patient’s he-modynamic status; however, blood pressure is an indirect

method of monitoring tissue hypoxia. Pulse pressure correlates well to stroke

volume, the amount of blood ejected from the heart with systole. Pulse pressure

is calculated by subtracting the diastolic measurement from the systolic

measurement; the difference is the pulse pressure. Normally, the pulse pressure

is 30 to 40 mm Hg (Mikhail, 1999). Narrowing or decreased pulse pressure is an

earlier indicator of shock than a drop in systolic blood pressure. Decreased or

narrowing pulse pressure, an early indication of de-creased stroke volume, is

illustrated in the following example:

Systolic blood pressure − diastolic blood pressure = pulse pressure

Elevation in the diastolic blood pressure with release of

cate-cholamines and attempts to increase venous return through

vaso-constriction is an early compensatory mechanism in response to decreased

stroke volume, blood pressure, and overall cardiac output.

Although treatments are prescribed and initiated by the physi-cian, the nurse usually implements them, operates and trou-bleshoots equipment used in treatment, monitors the patient’s status during treatment, and assesses the immediate effects of treatment. Additionally, the nurse assesses the response of the pa-tient and the family to the crisis and to treatment.

REDUCING ANXIETY

While experiencing a

major threat to health and well-being and being the focus of attention of many

health care providers, the patient often becomes anxious and apprehensive.

Providing brief explanations about the diagnostic and treatment procedures,

sup-porting the patient during those procedures, and providing in-formation

about their outcomes are usually effective in reducing stress and anxiety and

thus promoting the patient’s physical and mental well-being.

PROMOTING SAFETY

Another nursing intervention is monitoring potential threats to the

patient’s safety, because a high anxiety level and altered men-tal status

typically impair a person’s judgment. In this stage, pa-tients who were

previously cooperative and followed instructions may now disrupt intravenous

lines and catheters and complicate their condition. Therefore, close monitoring

is essential.

PROGRESSIVE STAGE

In the progressive stage of shock, the mechanisms that regulate blood

pressure can no longer compensate and the MAP falls below normal limits, with

an average systolic blood pressure of less than 90 mm Hg (Abraham et al.,

2000).

Pathophysiology

Although all organ systems suffer from hypoperfusion at this stage, two

events perpetuate the shock syndrome. First, the over-worked heart becomes

dysfunctional; the body’s inability to meet increased oxygen requirements

produces ischemia; and biochem-ical mediators cause myocardial depression

(Kumar, Haery & Parrillo, 2000; Price, Anning, Mitchell et al., 1999). This

leads to failure of the cardiac pump, even if the underlying cause of the shock

is not of cardiac origin. Second, the autoregulatory func-tion of the

microcirculation fails in response to numerous bio-chemical mediators released

by the cells, resulting in increased capillary permeability, with areas of

arteriolar and venous con-striction further compromising cellular perfusion. At

this stage, the patient’s prognosis worsens. The relaxation of precapillary

sphincters causes fluid to leak from the capillaries, creating inter-stitial

edema and return of less fluid to the heart. Even if the underlying cause of

the shock is reversed, the breakdown of the circulatory system itself

perpetuates the shock state, and a vicious circle ensues.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Chances of survival depend on the patient’s general health before the

shock state as well as the amount of time it takes to restore tis-sue

perfusion. As shock progresses, organ systems decompensate.

RESPIRATORY EFFECTS

The lungs, which become compromised early in shock, are af-fected at

this stage. Subsequent decompensation of the lungs in-creases the likelihood

that mechanical ventilation will be needed if shock progresses. Respirations

are rapid and shallow. Crackles are heard over the lung fields. Decreased

pulmonary blood flow causes arterial oxygen levels to decrease and carbon

dioxide levels to increase. Hypoxemia and biochemical mediators cause an

in-tense inflammatory response and pulmonary vasoconstriction, perpetuating the

pulmonary capillary hypoperfusion and hypox-emia. The hypoperfused alveoli stop

producing surfactant andsubsequently collapse. Pulmonary capillaries begin

to leak their contents, causing pulmonary edema, diffusion abnormalities

(shunting), and additional alveolar collapse. Interstitial inflam-mation and

fibrosis are common as the pulmonary damage pro-gresses (Fein &

Calalang-Colucci, 2000). This condition is sometimes referred to as acute

respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute lung injury (ALI), shock lung, or

noncardiogenic pulmonary edema.

CARDIOVASCULAR EFFECTS

A lack of adequate blood supply leads to dysrhythmias and is-chemia. The

patient has a rapid heart rate, sometimes exceeding 150 bpm. The patient may

complain of chest pain and even suf-fer a myocardial infarction. Cardiac enzyme

levels (eg, lactate de-hydrogenase, CPK-MB, and cTn-I) rise. In addition,

myocardial depression and ventricular dilation may further impair the heart’s

ability to pump enough blood to the tissues to meet oxygen requirements.

NEUROLOGIC EFFECTS

As blood flow to the brain becomes impaired, the patient’s men-tal

status deteriorates. Changes in mental status occur as a re-sult of decreased

cerebral perfusion and hypoxia; the patient may initially exhibit confusion or

a subtle change in behavior. Subsequently, lethargy increases and the patient

begins to lose consciousness. The pupils dilate and are only sluggishly

reactive to light.

RENAL EFFECTS

When the MAP falls below

80 mm Hg (Guyton & Hall, 2000), the glomerular filtration rate of the

kidneys cannot be main-tained, and drastic changes in renal function occur.

Acute renal failure (ARF) can develop. ARF is characterized by an increase in

blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine levels, fluid and electrolyte

shifts, acid–base imbalances, and a loss of the renal-hormonal regulation of

blood pressure. Urinary output usually decreases to below 0.5/mL/kg per hour

(or below 30 mL per hour) but can be variable depending on the phase of ARF.

HEPATIC EFFECTS

Decreased blood flow to the liver impairs the liver cells’ ability to

perform metabolic and phagocytic functions. Consequently, the patient is less

able to metabolize medications and metabolic waste products, such as ammonia

and lactic acid. The patient becomes more susceptible to infection as the liver

fails to filter bacteria from the blood. Liver enzymes (aspartate

aminotransferase [AST], formerly serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase

[SGOT]; alanine aminotransferase [ALT], formerly serum gluta-mate pyruvate

transaminase [SGPT]; lactate dehydrogenase) and bilirubin levels are elevated,

and the patient appears jaundiced.

GASTROINTESTINAL EFFECTS

Gastrointestinal ischemia can cause stress ulcers in the stomach,

placing the patient at risk for gastrointestinal bleeding. In the small

intestine, the mucosa can become necrotic and slough off, causing bloody

diarrhea. Beyond the local effects of impaired per-fusion, gastrointestinal

ischemia leads to bacterial toxin translo-cation, in which bacterial toxins

enter the bloodstream through the lymph system. In addition to causing

infection, bacterial tox-ins can cause cardiac depression, vasodilation,

increased capillary permeability, and an intense inflammatory response with

activation of additional biochemical mediators. The net result is inter-ference

with healthy cells and their ability to metabolize nutrients (Balk, 2000b;

Jindal et al., 2000).

HEMATOLOGIC EFFECTS

The combination of hypotension, sluggish blood flow, metabolic acidosis,

and generalized hypoxemia can interfere with normal hemostatic mechanisms.

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) can occur either as a cause or as

a complication of shock. In this condition, widespread clotting and bleeding

occur simul-taneously. Bruises (ecchymoses) and bleeding (petechiae) may

ap-pear in the skin. Coagulation times (prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin

time) are prolonged. Clotting factors and platelets are consumed and require

replacement therapy to achieve hemostasis.

Medical Management

Specific medical management in the progressive stage of shock depends on

the type of shock and its underlying cause. It is also based on the degree of

decompensation in the organ systems. Medical management specific to each type

of shock is discussed in later sections. Although there are several

differ-ences in medical management by type of shock, some medical

in-terventions are common to all types. These include use of appropriate

intravenous fluids and medications to restore tissue perfusion by (1)

optimizing intravascular volume, (2) supporting the pumping action of the

heart, and (3) improving the compe-tence of the vascular system. Other aspects

of management may include early enteral nutritional support and use of

antacids, histamine-2 blockers, or antipeptic agents to reduce the risk of

gastrointestinal ulceration and bleeding.

Nursing Management

Nursing care of the

patient in the progressive stage of shock re-quires expertise in assessing and

understanding shock and the sig-nificance of changes in assessment data. The

patient in the progressive stage of shock is often cared for in the intensive

care setting to facilitate close monitoring (hemodynamic monitoring,

electrocardiographic monitoring, arterial blood gases, serum elec-trolyte

levels, physical and mental status changes), rapid and fre-quent administration

of various prescribed medications and fluids, and possibly intervention with

supportive technologies, such as mechanical ventilation, dialysis, and

intra-aortic balloon pump.

Working closely with other members of the health care team, the nurse

carefully documents treatments, medications, and flu-ids that are administered

by members of the team, recording the time, dosage or volume, and the patient’s

response. Additionally, the nurse coordinates both the scheduling of diagnostic

proce-dures that may be carried out at the bedside and the flow of health care

personnel involved in the patient’s care.

PREVENTING COMPLICATIONS

If supportive technologies are used, the nurse helps reduce the risk of

related complications and monitors the patient for early signs of

complications. Monitoring includes evaluating blood lev-els of medications,

observing invasive vascular lines for signs of infection, and checking

neurovascular status if arterial lines are inserted, especially in the lower

extremities. Simultaneously, the nurse promotes the patient’s safety and

comfort by ensuring thatall procedures, including invasive procedures and

arterial and ve-nous punctures, are carried out using correct aseptic

techniques and that venous and arterial puncture and infusion sites are

main-tained with the goal of preventing infection. Positioning and

repositioning the patient to promote comfort, prevent pul-monary complications,

and maintain skin integrity are integral to caring for the patient in shock.

PROMOTING REST AND COMFORT

Efforts are made to minimize the cardiac workload by reducing the

patient’s physical activity and fear or anxiety. Promoting rest and comfort is

a priority in the patient’s care. To ensure that the patient gets as much

uninterrupted rest as possible, the nurse per-forms only essential nursing activities.

To conserve the patient’s energy, the nurse protects the patient from

temperature extremes (excessive warmth or shivering cold), which can increase

the metabolic rate and subsequently the cardiac workload. The pa-tient should

not be warmed too quickly, and warming blankets should not be applied because

they can cause vasodilation and a subsequent drop in blood pressure.

SUPPORTING FAMILY MEMBERS

Because the patient in shock is the object of intense attention by the

health care team, the family members may feel neglected; how-ever, they may be

reluctant to ask questions or seek information for fear that they will be in

the way or will interfere with the at-tention given to the patient. The nurse

should make sure that the family is comfortably situated and kept informed

about the pa-tient’s status. Often, family members need advice from the health

care team to get some rest; they are more likely to take this advice if they

feel that the patient is being well cared for and that they will be notified of

any significant changes in the patient’s status. A visit from the hospital

chaplain may be comforting to the family and provides some attention to the

family while the nurse concentrates on the patient.

IRREVERSIBLE STAGE

The irreversible (or refractory) stage of shock represents the point

along the shock continuum at which organ damage is so severe that the patient

does not respond to treatment and cannot sur-vive. Despite treatment, blood

pressure remains low. Complete renal and liver failure, compounded by the

release of necrotic tissue toxins, creates an overwhelming metabolic acidosis.

Anaer-obic metabolism contributes to a worsening lactic acidosis. Re-serves of

ATP are almost totally depleted, and mechanisms for storing new supplies of

energy have been destroyed. Multiple organ dysfunction progressing to complete

organ failure has oc-curred, and death is imminent. Multiple organ dysfunction

can occur as a progression along the shock continuum or as a syn-drome unto

itself.

Medical Management

Medical management during the irreversible stage of shock is usually the

same as for the progressive stage. Although the pa-tient’s condition may have

progressed from the progressive to the irreversible stage, the judgment that

the shock is irreversible can be made only retrospectively on the basis of the

patient’s failure to respond to treatment. Strategies that may be experimental

(ie, investigational medications, such as antibiotic agents and

immunomodulation therapy) may be tried to reduce or reverse the severity of

shock.

Nursing Management

As in the progressive

stage of shock, the nurse focuses on carry-ing out prescribed treatments,

monitoring the patient, preventing complications, protecting the patient from

injury, and providing comfort. Offering brief explanations to the patient about

what is happening is essential even if there is no certainty that the patient

hears or understands what is being said.

As it becomes obvious

that the patient is unlikely to survive, the family needs to be informed about

the prognosis and likely outcomes. Opportunities should be provided, throughout

the pa-tient’s care, for the family to see, touch, and talk to the patient. A

close family friend or spiritual advisor may be of comfort to the family in

dealing with the inevitable death of the patient. When-ever possible and

appropriate, the family should be approached regarding any living will, advance

directive, or other written or verbal wishes the patient may have shared in the

event that he or she cannot participate in end-of-life decisions. In some

cases, ethics committees may assist the family and health care team in making

difficult decisions.

During this stage of

shock, families may misinterpret the ac-tions of the health care team. They

have been told that nothing has been effective in reversing the shock and that

the patient’s sur-vival is very unlikely, yet the health care team continues to

work feverishly on the patient. A distraught, grieving family may inter-pret

this as a chance for recovery when none exists. As a result, family members may

become angry when the patient dies. Con-ferences with all members of the health

care team and the family will promote better understanding by the family of the

patient’s prognosis and the purpose for the measures being taken. During these

conferences, it is essential to explain that the equipment and treatments being

provided are for the patient’s comfort and do not suggest that the patient will

recover. Families should be encour-aged to express their wishes concerning the

use of life-support measures.

Related Topics