Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Shock and Multisystem Failure

Septic Shock - Circulatory Shock

SEPTIC

SHOCK

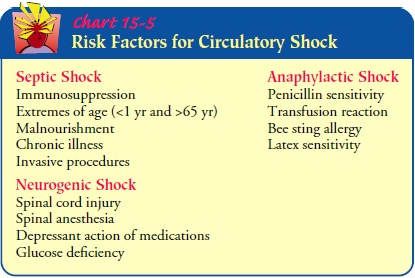

Septic shock is the most common type of circulatory shock and is caused

by widespread infection (Chart 15-5). Despite the in-creased sophistication of

antibiotic therapy, the incidence of sep-tic shock has continued to rise during

the past 60 years. It is the most common cause of death in noncoronary

intensive care units in the United States and the 13th leading cause of death

in the U.S. population (Balk, 2000a). Elderly patients are at particular risk

for sepsis because of decreased physiologic reserves and an aging immune system

(Balk, 2000a; Vincent & Ferreira, 2000).

Nosocomial infections (infections occurring in the hospital) in critically ill patients most frequently originate in the blood-stream, lungs, and urinary tract (in decreasing order of frequency) (Richards, Edwards, Culver et al., 1999). The source of infection is an important determinant of the clinical outcome. The great-est risk of sepsis occurs in patients with bacteremia (bloodstream) and pneumonia (Simon & Trenholme, 2000). Other infections that may progress to septic shock include intra-abdominal infec-tions, wound infections, bacteremia associated with intravascular catheters (Eggimann & Pittet, 2001), and indwelling urinary catheters.

Additional risk factors that contribute to the growing incidence of septic shock are the increased awareness and identification of septic shock; the increased number of immunocom-promised

patients (due to malnutrition, alcoholism, malignancy, and diabetes mellitus);

the increased incidence of invasive proce-dures and indwelling medical devices;

the increased number of resistant microorganisms; and the increasingly older

population (Balk, 2000a). The incidence of septic shock can be reduced by

débriding wounds to remove necrotic tissue and carrying out in-fection control

practices, including the use of meticulous aseptic technique, properly cleaning

and maintaining equipment, and using thorough hand-hygiene techniques.

The most common causative microorganisms of septic shock are the gram-negative bacteria; however, there is also an increased incidence of gram-positive bacterial infections. Currently, gram-positive bacteria are responsible for 50% of bacteremic events (Simon & Trenholme, 2000). Other infectious agents such as viruses and funguses also can cause septic shock.

When a microorganism

invades body tissues, the patient ex-hibits an immune response. This immune response

provokes the activation of biochemical mediators associated with an

inflam-matory response and produces a variety of effects leading to shock.

Increased capillary permeability, which leads to fluid seep-ing from the

capillaries, and vasodilation are two such effects that interrupt the ability

of the body to provide adequate perfusion, oxygen, and nutrients to the tissues

and cells.

Septic shock typically

occurs in two phases. The first phase, referred to as the hyperdynamic,

progressive phase, is character-ized by a high cardiac output with systemic

vasodilation. The blood pressure may remain within normal limits. The heart

rate increases, progressing to tachycardia. The patient becomes hyper-thermic

and febrile, with warm, flushed skin and bounding pulses. The respiratory rate

is elevated. Urinary output may remain at normal levels or decrease.

Gastrointestinal status may be compro-mised as evidenced by nausea, vomiting,

diarrhea, or decreased bowel sounds. The patient may exhibit subtle changes in mental

status, such as confusion or agitation.

The later phase, referred to as the hypodynamic, irreversible phase, is

characterized by low cardiac output with vasoconstriction, reflecting the

body’s effort to compensate for the hypovolemia caused by the loss of

intravascular volume through the capillaries. In this phase, the blood pressure

drops and the skin is cool and pale. Temperature may be normal or below normal.

Heart and res-piratory rates remain rapid. The patient no longer produces

urine, and multiple organ dysfunction progressing to failure develops.

Systemic inflammatory

response syndrome (SIRS) presents clinically like sepsis. The only difference

between SIRS and sep-sis is that there is no identifiable source of infection.

SIRS stim-ulates an overwhelming inflammatory immunologic and hormonal

response, similar to that seen in septic patients. Despite an absence of

infection, antibiotic agents may still be adminis-tered because of the

possibility of unrecognized infection. Addi-tional therapies directed to the

support of the patient with SIRS are similar to those for sepsis. If the

inflammatory process pro-gresses, septic shock may develop.

Medical Management

Current treatment of septic shock involves identifying and elim-inating

the cause of infection. Specimens of blood, sputum, urine, wound drainage, and

invasive catheter tips are collected for culture using aseptic technique.

Any potential routes of infection must be eliminated. Intra-venous lines

are removed and reinserted at other body sites. Antibiotic-coated intravenous

central lines may be placed to de-crease the risk of invasive line-related

bacteremia in high-risk pa-tients, such as the elderly (Eggimann & Pittet,

2001). If possible, urinary catheters are removed. Any abscesses are drained

and necrotic areas débrided.

Fluid replacement must be instituted to correct the hypo-volemia that

results from the incompetent vasculature and in-flammatory response.

Crystalloids, colloids, and blood products may be administered to increase the

intravascular volume.

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

If the infecting organism is unknown, broad-spectrum antibiotic agents

are started until culture and sensitivity reports are received (Simon &

Trenholme, 2000). A third-generation cephalosporinplus an aminoglycoside may be

prescribed initially. This combi-nation works against most gram-negative and

some gram-positive organisms. When culture and sensitivity reports are

available, the antibiotic agent may be changed to one that is more specific to

the infecting organism and less toxic to the patient.

Research efforts show promise for improving the outcomes of septic

shock. Although past treatments focused on destroying the infectious organism,

emphasis is now on altering the patient’s im-mune response to the organism. The

cell walls of gram-negative bacteria contain a lipopolysaccharide, an endotoxin

released dur-ing phagocytosis (Abraham et al., 2001). Endotoxin and/or

gram-positive cell wall products interact with inflammatory bio-chemical

mediators, initiating an intense inflammatory response and systemic effects

that lead to shock. Current research focuses on the development of medications

that will inhibit or modulate the effects of biochemical mediators, such as

endotoxin and pro-calcitonin (Bernard, Vincent, Laterre, et al., 2001). The

focus on immunotherapy in treating septic shock is expected to shed light on

how the cellular response to infection leads to shock.

Recombinant human activated protein C (APC), or drotreco-gin alfa

(Xigris), has recently been demonstrated to reduce mor-tality in patients with

severe sepsis (Bernard, Artigas, Dellinger et al., 2001). It has been approved

by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of adults with severe

sepsis and re-sulting acute organ dysfunction who are at high risk of death. It

acts as an antithrombotic, anti-inflammatory, and profibrinolytic agent. Its

most common serious side effect is bleeding. Therefore, it is contraindicated

in patients with active internal bleeding, re-cent hemorrhagic stroke, intracranial

surgery, or head injury.

NUTRITIONAL THERAPY

Aggressive nutritional supplementation is critical in the manage-ment of

septic shock because malnutrition further impairs the pa-tient’s resistance to

infection. Nutritional supplementation should be initiated within the first 24

hours of the onset of shock (Mizock, 2000). Enteral feedings are preferred to

the parenteral route be-cause of the increased risk of iatrogenic infection

associated with intravenous catheters; however, enteral feedings may not be possi-ble

if decreased perfusion to the gastrointestinal tract reduces peri-stalsis and

impairs absorption.

Nursing Management

The nurse caring for any patient in any setting must keep in mind the

risks of sepsis and the high mortality rate associated with sep-tic shock. All

invasive procedures must be carried out with aseptic technique after careful

hand hygiene. Additionally, intravenous lines, arterial and venous puncture

sites, surgical incisions, trau-matic wounds, urinary catheters, and pressure

ulcers are moni-tored for signs of infection in all patients. The nurse

identifies patients at particular risk for sepsis and septic shock (ie, elderly

and immunosuppressed patients or patients with extensive trauma or burns or

diabetes), keeping in mind that these high-risk patients may not develop

typical or classic signs of infection and sepsis. Confusion, for example, may

be the first sign of infection and sep-sis in elderly patients.

When caring for the

patient with septic shock, the nurse col-laborates with other members of the

health care team to identify the site and source of sepsis and the specific

organisms involved. Appropriate specimens for culture and sensitivity are often

ob-tained by the nurse.

Elevated body temperature (hyperthermia) is common with sepsis and

raises the patient’s metabolic rate and oxygen con-sumption. Fever is one of

the body’s natural mechanisms for fighting infections. Thus, an elevated

temperature may not be treated unless it reaches dangerous levels (more than

40C [104F]) or unless the patient is uncomfortable. Efforts may be made to

reduce the temperature by administering acetaminophen or applying hypothermia

blankets. During these therapies, the nurse monitors the patient closely for

shivering, which increases oxygen consumption. Efforts to increase comfort are

important if the patient experiences fever, chills, or shivering.

The nurse administers prescribed intravenous fluids and med-ications,

including antibiotic agents and vasoactive medications to restore vascular

volume. Because of decreased perfusion to the kidneys and liver, serum

concentrations of antibiotic agents that are normally cleared by these organs

may increase and produce toxic effects. Therefore, the nurse monitors blood

levels (anti-biotic agent, BUN, creatinine, white blood count) and reports

in-creased levels to the physician.

As with other types of

shock, the nurse monitors the patient’s hemodynamic status, fluid intake and

output, and nutritional sta-tus. Daily weights and close monitoring of serum

albumin levels help determine the patient’s protein requirements.

Related Topics