Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Principles of Laboratory Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases

Specimen - Laboratory Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases

THE SPECIMEN

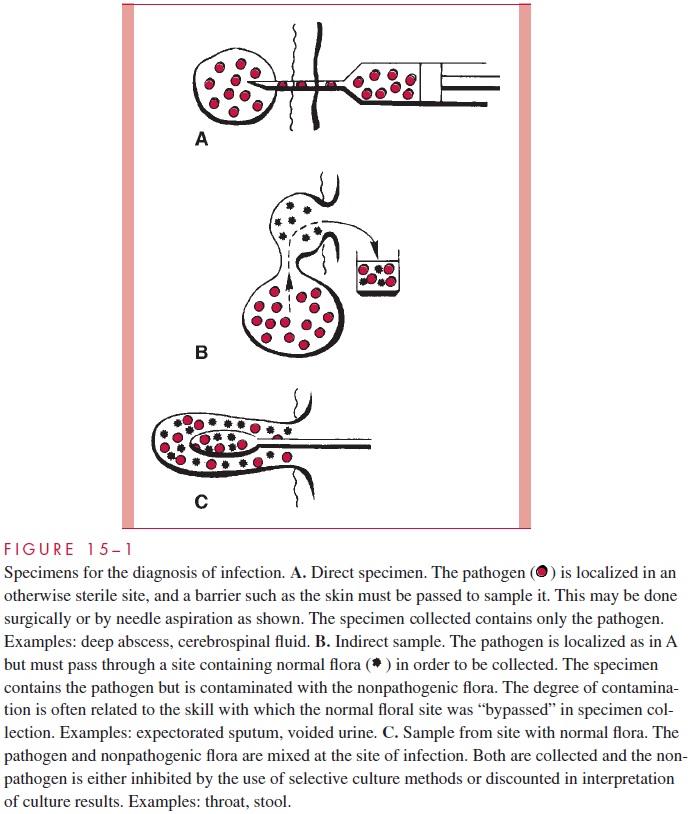

The primary connection between the clinical encounter and diagnostic laboratory is the specimen submitted for processing. If it is not appropriately chosen and/or collected, no degree of laboratory skill will rectify the error. Failure at the level of specimen collection is the most common reason for failure to establish an etiologic diagnosis, or worse, for suggesting a wrong diagnosis. In the case of bacterial infections, the primary problem lies in distinguishing resident or contaminating normal floral organisms from those causing the infection.

Direct Tissue or Fluid Samples

Direct specimens (Fig 15 – 1A) are collected from normally sterile tissues (lung, liver) and body fluids (cerebrospinal fluid, blood). The methods range from needle aspiration of an abscess to surgical biopsy. In general, such collections require the direct involvement of a physician and may carry some risk for the patient. The results are always useful, be-cause positive findings are diagnostic and negative findings can exclude infection at the suspected site.

Indirect Samples

Indirect samples (Fig 15 – 1B) are specimens of inflammatory exudates (expectorated spu-tum, voided urine) that have passed through sites known to be colonized with normal flora. The site of origin is usually sterile in healthy persons; however, some assessment of the probability of contamination with normal flora during collection is necessary before these specimens can be reliably interpreted. This assessment requires knowledge of the potential contaminating flora as well as the probable pathogens to be sought. Indirect samples are usually more convenient for both physician and patient, but carry a higher risk of misinterpretation. For some specimens, such as expectorated spu-tum, guidelines to assess specimen quality have been developed by correlation of clinical and microbiologic findings .

Samples from Normal Flora Sites

Frequently the primary site of infection is in an area known to be colonized with many organisms (pharynx and large intestine) (Fig 15 – 1C). In such instances, examinations are selectively made for organisms known to cause infection that are not normally found at the infected site. For example, Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter may be specifi-cally sought in a stool specimen because they are known to cause diarrhea. It is neither practical nor relevant to describe the other stool flora.

Specimens for Viral Diagnosis

The selection of specimens for viral diagnosis is easier because there is essentially little normal viral flora to confuse interpretation. This allows selection guided by knowledge of which sites are most likely to yield the suspected etiologic agent. For example, en-teroviruses are the most common viruses involved in acute infection of the central ner-vous system. Specimens that might be expected to yield these agents on culture include throat, stool, and cerebrospinal fluid.

Specimen Collection and Transport

The sterile swab is the most convenient and most commonly used tool for specimen col-lection; however, it provides the poorest conditions for survival and can only absorb a small volume of inflammatory exudate. The worst possible specimen is a dried-out swab; the best is a collection of 5 to 10 mL or more of the infected fluid or tissue. The volume is important because infecting organisms present in small numbers may not be detected in a small sample.

Specimens should be transported to the laboratory as soon after collection as possi-ble, because some microorganisms survive only briefly outside the body. For example, unless specialtransport media are used, isolation rates of the organism that causes gonorrhea (Neisseria gonorrhoeae) are decreased when processing is delayed beyond a few minutes. Likewise, many respiratory viruses survive poorly outside the body. On the other hand, some bacteria survive well and may even multiply after the specimen is collected. The growth of enteric Gram-negative rods in specimens awaiting culture may in fact compromise specimen interpretation and interfere with the isolation of more fastidious organisms. Significant changes are associated with delays of more than 3 to 4 hours.

Various transport media have been developed to minimize the effects of the delay be-tween specimen collection and laboratory processing. In general, they are buffered fluid or semisolid media containing minimal nutrients and are designed to prevent drying, maintain a neutral pH, and minimize bacterial growth. Other features may be required to meet special requirements, such as an oxygen-free atmosphere for obligate anaerobes.

Related Topics