Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Social Psychology

Social Psychology: Culture and Social Psychology

Culture and Social Psychology

Social psychologists increasingly have appreciated

the influence of culture on psychological functioning (Fiske et al., 1998; Kim and Berry, 1993;

Moghaddam et al., 1993; Matsumoto,

2001). Consistent with this trend, Fiske and colleagues (1998) have pro-posed a

mutual constitution of psychological and cultural life. Specifically, these

investigators suggest that culture influences psychological functioning which

in turn can change cultural ex-pressions. They further argue that although the

human tendency to form cultures sprang from evolutionary processes, culture, in

turn, has exerted an influence on the subsequent course of evolution.

Myriad definitions of culture have been proposed by

social scientists across a range of disciplines. Culture can be defined as a

collective organization of behaviors, ideas, attitudes, values, beliefs and

customs shared by a group of people, and socially transmitted across

generations through language and/or other modes of communication. As this

definition suggests, cultural processes are of core importance to individual

psychological functioning, as they influence the cognitive, affective and

behav-ioral aspects of a range of personal and social activities. Factors that

influence the manner in which cultural patterns are mani-fested in

interpersonal relationships include gender, ethnicity, race, socioeconomic

status, educational background, neighbor-hood and geographic region of

residence, country of origin, transmigration patterns, religious and political

affiliations, and stage in the life-cycle.

Social psychological researchers have emphasized

the importance of distinguishing culture-specific from universal

psychological findings (Triandis, 1997). This is

illustrated by the conceptual distinction between emics (findings that differ across cultures and suggest culture-specific

psychological principles) and etics

(findings that apply across cultures and suggest universal psychological

principles) (Matsumoto, 1994). Given cultural in-fluences on psychological

phenomena, a cross-cultural approach is presumed to be essential for the

articulation of universal prin-ciples (Moghaddam et al., 1993). Theorists and researchers who take a cultural

perspective have argued persuasively that many findings from social

psychological research in the USA reflect specific cultural dynamics and are

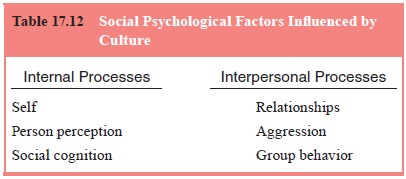

not necessarily universally ap-plicable (Moghaddam et al., 1993; Triandis, 1997). Culture influ-ences the

understanding of self, social cognition, relationships and group behavior

(Table 17.12).

Culture affects definitions and causal explanations

of health and illness, as well as the nature and quality of help-seeking

behavior (Kazarian and Evans, 2001; MacLachlan, 1997). Given that one’s

ethnomedical system influences one’s involvement in the health care system as

either patient or health professional, it is essential to inquire about the

patient’s “explanatory models” of health and illness and to be cognizant of the

match between the doctor’s and patient’s world view vis-à-vis illness and its treatment (Kleinman, 1988). Further, it

behoves health providers and patients to acknowledge that medicine as practiced

in hospitals forms a subculture consisting of specific values, beliefs, and

practices (i.e., the culture of medicine). In this regard, interactions between

patients and health care providers can be viewed as cross-cultural

communications, with all participants working to comprehend one another’s world

views.

Recent work emphasizing the understanding of

psychological functioning from a cultural perspective has led mental health practitioners

to recognize culture as central to the conceptualization, assessment, and

treatment of clinically significant emotional and behavioral problems

(Gopaul-McNicol and Armour-Thomas, 2002; Kleinman, 1988; Tseng 2001; Tseng and

Streltzer, 2001). A cultural perspective has important implications for

defining and conceptualizing normal and abnormal behavior, with some arguing

that dichotomizing behavior as either normal or abnormal reflects historically

Western scientific cultural constructions (Foulks, 1991). A cultural

perspective is also important for developing and implementing culturally

sensitive interventions. There is considerable evidence to suggest that culture

influences many of the psychological and social variables typically associated with

psychological development, including child-rearing practices and customs,

constellation and structure of family life, communication and emotional

expression, social support networks, frequency and quality of life stress, the

ways in which difficulties are defined and managed, and values regarding

help-seeking behavior for emotional distress (Foulks, 1991). As cultural

differences across these domains vary, manifestations of psychological and

personality dysfunction also will differ (Foulks, 1991). This particularly

isapplicable to disorders that are thought to derive more from social and

environmental influences than from biological factors.

Implicit in Western models of psychiatric nosology

are a number of culture-bound assumptions regarding mental health and

psychiatric disorder. Examples of North American culture-bound biases

articulated by Lewis-Fernandez and Kleinman (1994) include: 1) an emphasis on

individuality and autonomy (egocentric view of self) as opposed to a more

interdependent emphasis (sociocentric view of self); 2) a view that

psychopatho-logical conditions have either an organic or a psychological

etiol-ogy but not both simultaneously (mind–body dualism versus a more

integrated somatopsychological view); and 3) an assump-tion that cultural

effects on psychological functioning are epiphe-nomena underneath which can be

found a universally knowable biological reality. The tendency to organize one’s

understanding of behavior according to these biases must be monitored

care-fully in work with patients. Further, clinicians and researchers need to

contextualize behavior and experience, and use relevant cultural norms to

understand behavioral difficulties and their adaptive value (Lewis-Fernandez

and Kleinman, 1994).

The importance of cultural considerations in

psychiat-ric diagnosis has increasingly been recognized (Mezzich et al., 1996). Cross-cultural social

scientists have investigated psychiat-ric epidemiology in different cultures,

with particular attention to schizophrenia spectrum disorders and mood

disorders. This work primarily has been conducted using an etic approach.

Although there is considerable evidence that supports the universality of

schizophrenia, cross-cultural differences in symptom expression and course have

been reported (Kulhara and Chakrabarti, 2001). An additional area of work that

approaches diagnostic classifica-tion from an emic perspective is that of

culture-bound syndromes or folk diagnostic categories, defined as “… certain

recurrent, lo-cality-specific patterns of aberrant behavior and experience that

appear to fall outside conventional Western psychiatric diagnos-tic categories”

(Simons and Hugnes, 1993, p. 75). These disorders reflect symptom patterns that

are linked to the cultural context within which they are embedded. Examples of

culture-bound syndromes in Western societies include anorexia nervosa and the

type A behavior pattern (Simons and Hugnes, 1993).

In addition to influencing assessment and

diagnosis, cul-tural variables should be taken into account in psychotherapeutic

endeavors. In this regard, cultural considerations are important in

understanding the conditions under which mental health treat-ment may be

sought, the type of approaches that would be most effective, the clinical

stance of the therapist within the treatment setting, and the nature of the

therapeutic relationship. Effective psychotherapy requires sensitivity to

differences that may affect the therapist’s and the patient’s perspective on

the problem, treat-ment method, and therapeutic process and objectives. Thus,

it is important for therapists to be cognizant of the patient’s cultur-ally

defined values and belief systems, definitions of normality and

psychopathology, problem-solving styles, communication patterns, interpersonal

customs and family role behaviors. This cultural perspective is essential when

working with adults (Tseng and Streltzer, 2001), children (Canino and Spurlock,

1994; Vargas and Koss-Chioino, 1992) and families (McGoldrick et al., 1996).

Related Topics