Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Social Psychology

Social Psychology: Social Cognition

Social Cognition

Social cognition – the ways social events are

interpreted, analyzed and mentally represented – provides an

information-processing framework for understanding how construals of self and

others affect social discourse and psychological life (Fiske and Taylor, 1991).

Social cognition concepts have influenced traditional areas of social

psychological theory and research, including attribution processes, person perception,

and attitude formation and change. Over time, the information processing

emphasis of social cogni-tion has been integrated with concepts of motivation

and emotion to create a fuller view of the individual in relation to the social

world (Taylor, 1998).

Attribution Processes

Attribution processes refer to causal explanations

generated by an individual to account for why a particular event or set of

out-comes has occurred. People use attributions to make sense of their own

behavior and that of others, and, therefore, attribution processes influence

individual actions, affective experiences and

interpersonal behavior (Weiner and Graham, 1999).

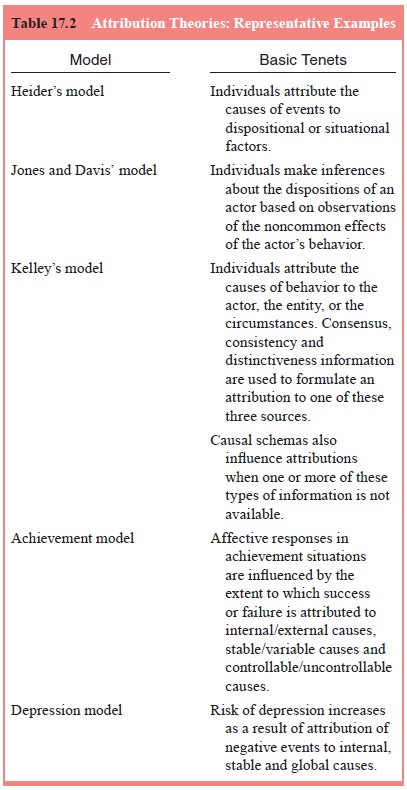

Attribution theory (Table 17.2) and research has been a mainstay of social

psychology and has led to important clinical mental health ap-plications

(Bell-Dolan and Anderson, 1999; Forsterling, 2001; Graham and Folkes, 1990).

Attribution Biases

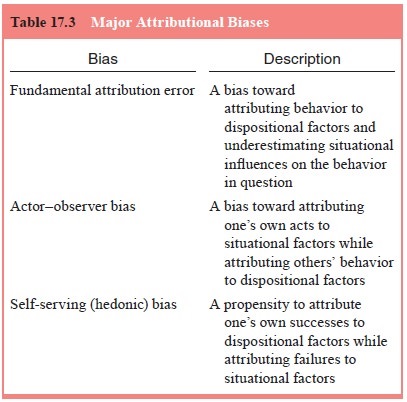

Based on the proliferation of research stimulated

in the 1970s by social psychological models of causal attribution, three major

types of attribution biases in everyday social interactions were illuminated:

the fundamental attribution error (Ross, 1977), the actor–observer bias (Jones

and Nisbett, 1971) and the self-serving (hedonic) attribution bias (Bradley,

1978) (Table 17.3).

The fundamental attribution error – a bias toward

at-tributing behavior to dispositional factors in the actor while

underestimating the influence of situational variables – typically occurs in

the context of understanding the behavior of others.

The actor–observer bias refers to instances in

which individuals attribute their own acts to situational factors and minimize

the role of dispositional qualities, attributing the others’ behavior to

dispo-sitional factors. Actor–observer differences may be a function of greater

self-knowledge than knowledge of others, or related to dif-fering perspectives

between actors and observers that lead to dif-ferent causal interpretations.

The self-serving (hedonic) attribution bias involves a propensity to attribute

one’s successes to disposi-tional factors and one’s failures to situational

causes. Specifically, the self-serving bias reflects a wish to present oneself

in the best possible light. People tend to extend this attribution bias to

impor-tant others in their interpersonal sphere (e.g., spouse). Multiple

ex-planations have been offered in the literature regarding the causal

underpinnings of these attribution biases (Forsterling, 2001).

Attributions in Health and Illness

Given that attribution processes tend to be

activated by negative, unanticipated, or ambiguous events, it is logical to

assume that attribution theory would have a useful role in conceptualizing how

people come to understand the causes of their illness as well as processes of

stress and coping with illness (Amirkhan, 1990; Salovey et al., 1998). Empirical evidence supports this view, as

exemplified in a recent meta-analytic study that suggested that attributions

influence illness-related coping and adjust-ment (Roesch and Weiner, 2001).

Attributions influence one’s self-definitions in relation to the illness, as

well as one’s percep-tions of control over illness-related contingencies and

outcomes. However, associations between specific attributions and illness

should not be interpreted to mean that certain attribution patterns cause

illness, but rather that they may be among a complex set of factors affecting

responses to illness.

It is clear that causal attributions are important

in facilitat-ing health promotion and positive health practices (Rodin and

Salovey, 1989; Salovey et al., 1998).

To the extent possible, treat-ment interventions with medically ill persons

should incorporate a focus upon enhancing the individual perceptions of control

over health and treatment regimens with the aim of increasing adher-ence to

medical regimens and improving adjustment to medical procedures and conditions.

Existing research also underscores the importance of considering locus,

stability and controlla-bility dimensions of the attribution process in

understanding illness-related attribution processes and their role in

predicting patient perceptions of medical treatment (Amirkhan, 1990).

Mental Health Implications: Attribution Processes

Theoretical models and research have significant

implications for mental health treatment (Bell-Dolan and Anderson, 1999;

Forsterling, 2001; Weiner and Graham, 1999). Presumably, at-tribution models

can be instructive for designing interventions that target causal inferences

associated with problematic emo-tion states (e.g., guilt), moods (e.g.,

depression) and behavioral constellations (e.g., social avoidance) (Bell-Dolan

and Anderson, 1999). The application of attribution models to depression is

illustrative of this point.

Hopelessness Theory of Depression

The use of attribution concepts, including the

notion of attribu-tional style, in understanding learned helplessness and

depression led to the formulation that the presence of a pessimistic

attribu-tional style increased the risk that an individual would experi-ence

helplessness, hopelessness and depression (Abramson et al., 1978). This attribution dimension was later incorporated as

a key component of the hopelessness theory of depression (Abramson et al., 1989; Gotlib and Abramson, 1999).

This model predicts that an

individual is at risk for hopelessness depression to the extent that negative

events are attributed to internal, stable and global causes, and that these

causes are perceived as both likely to prompt other negative consequences and

to be reflective of deficiencies or shortcomings of self. The model also posits

that a given individual’s causal attributions are a function of both

situational factors and individual differences in attributional style. Further,

cognitive vulnerability to hopelessness depression is conceptualized as a

function of individual differences in at-tributional style as well as the

propensity to infer negative consequences and negative self-evaluation in

response to adverse events (Gotlib and Abramson, 1999).

Person Perception and Implicit Personality Theories

Person perception, also referred to as social

perception, pertains to the ways in which people formulate impressions of

others (Leyens and Fiske, 1994). Person perception can be conceptu-alized broadly

as involving three sequential processes: 1) the identification of meaningful

acts by observation of overt actions based on the actor’s intentions or traits;

2) the formation of attri-butions about the acts; and 3) the integration of

attribution infer-ences into a unified impression of an individual (Gilbert,

1998). Social psychologists have long suggested that people formulate implicit

personality theories that consist of general beliefs about human

characteristics and patterns of covariation among person-ality traits

(Schneider, 1973). These knowledge systems facili-tate rapid formation of

inferences about the enduring personality qualities of other people in everyday

life by using assumptions about interrelationships among dispositional

qualities to draw conclusions about observed behavior. More recently, schema

concepts in social cognition have been investigated in order to specify

cognitive processes through which individuals organize and represent coherent

and meaningful impressions of others (Leyens and Fiske, 1994).

Although person perception variables per se have

not been explicitly discussed in the context of health issues, one particularly

useful application of this literature is in understand-ing relationships

between patients and their health care provid-ers. The doctor–patient

relationship is influenced in part by the affective and cognitive evaluations

that each make regarding the other. These person perception variables affect

interaction styles between physicians and their patients which, in turn, may

influence the nature and quality of medical care. Patients’ perceptions of

their physicians as paternalistic, interested in mutuality in decision-making

regarding care, or expecting them (the patient) to have primary responsibility

for decision-making will contribute to differential doctor–patient interaction

dynam-ics (Shelton, 1998). Similarly, the degree to which the physician’s

impression of the patient is that of a passive novice, informed part-ner, or

the consumer in charge of care will affect doctor–patient interactions.

Person perception has clinical relevance for the

cognitive interpretation of interpersonal situations. Many of the cognitive

distortions (e.g., overgeneralization, magnification and minimi-zation)

observed in depressed persons (Beck et al.,

1979), anxious individuals (Beck et al.,

1985), and people with personality disorders (Beck and Freeman, 1990) influence

person perception in a maladaptive fashion. Thus, while person perception

research has demonstrated a normative tendency to make rapid evalua-tions of

others and interpersonal situations based on limited information, this process

is apt to become problematic when cognitive distortions are operative. For

example, the depressed person with low self-esteem and a pessimistic

attributional style who, based on a few experiences of being criticized,

perceives others as judgmental in virtually every interpersonal interac-tion is

overgeneralizing based upon limited data (i.e., “others are always critical of

me”). This is likely to interfere with the development of trusting

relationships.

Implicit personality theories and schemas in social

cognition are clinically applicable to understanding chronically maladap-tive

person perception processes. This may have particular rel-evance for the

clinical understanding of personality disorders. For example, the patient with

paranoid personality disorder may hold a pervasive view of others as

potentially attacking, blaming and controlling (Benjamin, 1996). The patient

with borderline personality disorder may perceive others as simultaneously

rejecting, abandoning and needing dependent others (Benjamin, 1996). The

patient with obsessive–compulsive personality dis-order may believe that others

expect perfection regardless of the individual’s own wants and needs (Benjamin,

1996). To address these maladaptive implicit personality theories, schemas and

associated interaction patterns, effective psychotherapy helps patients

identify dysfunctional person perceptions, develop an affective and cognitive

awareness of the etiology of these beliefs and the functions they serve, and

form more adaptive schemas of self in relation to others (Benjamin, 1996).

Additionally, thera-pists’ awareness of problematic schemas and implicit

personality theories early in treatment can assist in assessment and

identifi-cation of interpersonal patterns that are likely to be enacted in the

therapeutic relationship.

Attitudes

Attitudes refer to evaluations made by people along

a contin-uum from positive to negative about specific entities called at-titude

objects (e.g., ideas, concrete things, life events, social groups, classes of

behavior, persons) (Eagly and Chaiken, 1998). Individual attitudes consist of

three elements: cognitive (beliefs about attitude objects), affective (emotions

elicited by attitude ob-jects) and behavioral (action intentions or overt

behavior directed toward attitude objects). Additionally, individual attitudes

may be associatively or logically linked to form broader inter-attitu-dinal

structures consisting of two or more attitudes (Eagly and Chaiken, 1998).

Attitudes provide a framework for rapid appraisal and evaluative interpretation

of one’s world, thereby allowing one to formulate responses to the complexities

and ambiguities of daily living in an economical fashion, often without the

need for deliberate, conscious processing (Cooper and Aronson, 1992).

Fundamentally, attitudes serve an important adaptive function by virtue of

their evaluative properties involving distinctions of good stimuli presumed to

enhance well-being from bad stimuli that could endanger well-being (Eagly and

Chaiken, 1998).

Attitude Theories

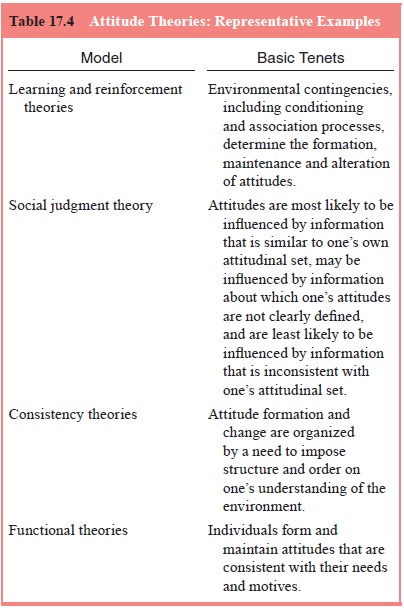

Attitude theory and research has a rich history as

one of the great areas of inquiry within social psychology (Eagly and Chaiken,

1998; Petty and Wegener, 1998). However, this voluminous and intricate

literature can be encapsulated only briefly here. Theo-retical frameworks

developed in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s that laid the foundation for later

social psychological inquiries into attitudes (Table 17.4).

Learning and reinforcement theories of attitude

formation and change, founded on principles of behaviorism, were derived

from basic experimental psychology. Two major

examples are conditioning (Staats and Staats, 1958) and associationist

(stimulus–response) (Hovland et al.,

1953) perspectives. These approaches emphasize the influence of stimulus

pairing and stimulus–response patterns in attitude formation (Eagly and

Chaiken, 1998).

Social judgment theory emphasizes the interplay of

cogni-tive and affective attitudinal components and posits that percep-tions

and judgments mediate attitude change (Sherif et al., 1965). According to this approach, attitudes are most

likely to be influ-enced by information that is similar to one’s existing

attitudinal set (i.e., latitude of acceptance), may be influenced by

informa-tion about which one’s attitudinal set is not clearly defined and

affectively neutral (i.e., latitude of noncommitment), and least likely to be

influenced by information that is inconsistent with one’s attitudinal set

(i.e., latitude of rejection).

Consistency theories posit that attitude formation

and change are organized by a need to impose structure and order on one’s

understanding of the environment. Cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, 1957)

posited that discrepancies between simultaneously held attitudinal cognitions

(dissonance) produced psychological tension, requiring attitudinal changes to

reestablish consistency (consonance). The degree to which this dissonance

causes psychological tension is a function of the per-sonal importance of the

cognitions and the number of dissonant cognitions relative to consonant

cognitions.

An alternative approach that proposed to account

for re-search findings regarding dissonance was self-perception theory (Bem,

1972). According to this perspective, individuals infer their attitudes through

observing their own behavioral responses and the conditions under which they

occur. From this view, at-titudes are formed on the basis of self-attributions

(Cooper and Aronson, 1992).

The final group of attitude theories – functional

theories – hold that individuals form and maintain attitudes consistent with

their needs and motives (Katz, 1960; Kelman, 1961; Smith et al., 1956). For example, particular attitudes may be adopted for

adjustment, instrumental, or utilitarian purposes, as they maximize rewards and

minimize punishments. Attitudes also may serve a value expression function.

Ego-defensive or ex-ternalizing functions of attitudes allow for maintenance of

de-sired views of self and the world, while protecting the individual from

acknowledgement of unpleasant realities. Attitudes serving a knowledge function

assist people in formulating meaning about events in their world. Functional

models suggest a complex interplay among different attitudinal beliefs,

necessitating dif-ferent change strategies based upon the function of the

attitude being targeted for change (Eagly and Chaiken, 1998).

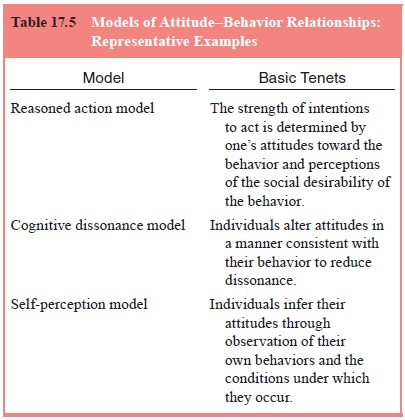

Interest in enhancing precision in the prediction

of behav-ioral responses from attitudinal beliefs prompted efforts to de-velop

models of the attitude–behavior relationship (Table 17.5). Two broad types of

models include those focusing on attitudes toward targets of behavior and those

focusing on attitudes toward behavior (Eagly and Chaiken, 1998).

Attitudes in Health and Illness

People’s attitudes affect whether or not they practice adap-tive or maladaptive health behaviors. Accordingly, it has been suggested that information aimed at promoting behaviors that reduce health risk should focus on attitudinal and normative beliefs influencing the behavior in question. The goal of such interventions is to bolster intentions to engage in or abstain from the target behavior.

Although not an attitude theory per se, the health

belief model (Rosenstock et al.,

1988; Strecher et al., 1997) is a

well-known social psychological model explicitly formulated to understand

health-related behavior practices. The health be-lief model posits that

individuals are motivated to respond to perceived threats of illness, with

threat defined in terms of per-ceptions regarding seriousness of and personal

susceptibility to an illness. Behavioral responses to health-related threats

are influenced by expectations regarding the ability to minimize such a threat,

including perceived benefits and problems associated with a given response

pattern. Sociocultural and demographic factors as well as personal and

environmental cues regarding ap-propriate courses of action also are considered

in the model. The model predicts that people are likely to take steps to

minimize the risk of contracting a medical problem if the following condi-tions

occur: 1) they view themselves as vulnerable to a particular health condition;

2) they deem the condition to be personally con-sequential; 3) they believe

that a specific course of action would minimize vulnerability to the condition

and that limitations as-sociated with such actions are outweighed by the

potential ben-efits to be accrued; and 4) they perceive themselves as capable

of performing these actions (i.e., self-efficacy). Researchers have examined

the utility of the health belief model in informing pre-vention and

intervention approaches for medically ill individuals and those at risk for

specific illnesses (Salovey et al.,

1998).

Attitudes can have an important impact on

psychological outlook and functioning. Whereas individuals who evidence

positive mental health possess flexible attitudes that are adaptive to the

context, persons with psychological difficulties evidence rigidly held

maladaptive attitudes that impair their capacity to cope effectively with

life’s challenges. This suggests that helping patients identify and modify

maladaptive attitudes about self and others can be an important component of

psychotherapeutic intervention (Cooper and Aronson, 1992).

Related Topics