Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Social Psychology

Social Psychology: Interpersonal Processes: The Egoism-Altruism Debate

The Egoism–Altruism Debate

Historically, the Western perspective has been that

human be-ings tend to be motivated by self-interest (egoism). It is therefore

not surprising that investigators concerned with prosocial be-havior have

debated the veracity of the concept of altruistically motivated prosocial acts

in which others are benefited with no apparent short-term or long-term benefits

for the helper. A model proposed by Batson (1987, 1998) is intended to account

for altruism without invoking self-serving motives by establish-ing empathy as

a key factor that drives altruistic behavior. Ac-cording to this

empathy–altruism hypothesis, empathy provides a vehicle for adopting the

perspective of the other in need that then motivates the helper to act with the

goal of benefiting the other. Because empathic emotion is distinguished from

that of a distress response, it is argued that helpful acts resulting from

empathic determinants are carried out with the intention of enhancing the

welfare of the other rather than the self. Three types of self-serving motives

have been proposed to challenge the empathy–altruism hypothesis, including the

prospect of self and social rewards for providing help, avoidance of self or

social punishment for failing to help, and reduction of aversive arousal associated

with feelings of empathy. In reviewing existing re-search, Batson (1998)

concluded that none of these self-serving motives could adequately account for

the relationship between empathy and helping behavior, and that, on balance,

empirical findings generally support the empathy–altruism hypothesis that there

are instances of altruism that can be distinguished from helping behavior

involving self-serving motives. Batson (1998) further proposed a general model

involving four categories of prosocial motivation, each of which is linked to

specific val-ues. These include egoism (valuing self-enhancement), altruism

(valuing other-enhancement at the level of the individual), col-lectivism

(valuing other-enhancement at the level of the social group), and principlism

(valuing maintaining faithfulness to specific moral ideals). Although ideally

these four categories of prosocial motivation operate in cooperative and

complementary ways, they also may at times come into conflict. In

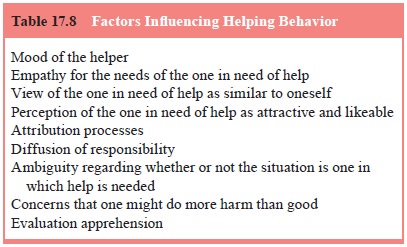

investigations of helping behavior, factors that influence whether or not an

in-dividual will engage in helping others, focus on characteristics of the

helper, the person who is in need of help, and the situation (Batson 1998)

(Table 17.8).

The high value placed on aiding those in ill-health

is ubiq-uitous in human life, exemplified at the cultural level by health care

professions and health care institutions entrusted to care for those in need of

medical intervention. Although multiple factors

contribute to the existence of health care

institutions and per-sonal decisions to work in health-related fields,

prosocial moti-vations are key among them. At the level of the individual, the

family and peer group, caring and empathy may propel the desire to help those

who are ill by providing emotional and instrumental support. As myriad

empirical investigations have shown, these prosocial acts of social support

provide beneficial health effects for individuals who receive them (Stroebe and

Stroebe, 1996).

Empathy engenders a sense of interest in and care

for oth-ers (Batson, 1998). The capacity for empathy is an important part of

healthy social relationships in that it enhances understanding of others and

thereby facilitates social connection and the sup-portive dimensions of

relationships. As such, clinical assessment should incorporate an evaluation of

empathy skills, especially in instances where clinical difficulties stem from

maladaptive rela-tional patterns. Consideration of the balance of empathic

versus self-serving interpersonal stances of the patient can be useful, not

only in individual psychotherapy but also in work with cou-ples seeking help in

resolving conflictual relationship patterns.

The clinical relevance of empathy extends to the

clinical practitioner. Therapist empathy is crucial to the understanding of the

patient and to the maintenance of the therapist’s concern for and desire to

enhance patient well-being. It is, therefore, hard to imagine the practice of

psychotherapy without empathic invest-ment of the therapist (Watson, 2002).

Although a powerful tool of therapeutic change, accurate empathy requires that

the thera-pist bear witness to considerable emotional pain in the process of

helping the patient. In some instances, the therapist may be overwhelmed by the

clinical issues of a given patient, and in re-sponse may retreat from an

empathic stance by distancing from, avoiding, or becoming numb to the

experience of the patient. It has been suggested that this empathic retreat is

a factor in the phenomenon of clinician burnout (Batson, 1998). As such,

em-pathic availability is an important variable for therapists to attend to in

their day-to-day work with patients.

Related Topics