Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Social Psychology

Social Psychology: The Self

Social psychology, defined broadly as the study of

social influences on psychological functioning, is highly relevant to a

biopsychosocial perspective in that it focuses on understanding the

person–environment relationship. Environmental factors are presumed to

influence psychological functioning. Individuals are defined as active

interpreters of the environmental contexts in which they live such that

individual construals of events influ-ence psychological life and behavior.

The Self

Theory and Research Findings

Historical Precedents

Current social psychological efforts to understand

the self in the context of the person–environment relationship, particularly

the social world of the individual, are not without significant historical

precedence. For example, James (1890/1981) posited that one com-ponent of the

self was a social self determined in part by rela-tionships with significant

others. James maintained that because one’s social roles and impact on others

are varied, each individual has multiple social selves (e.g., self at work,

self with family) with varying degrees of integration and internal consistency.

Cooley’s (1902) concept of the looking-glass self referred to the idea that the

self emerges from one’s interpretations of the reactions of im-portant others

in the social environment. Similarly, Mead’s (1934) symbolic interactionism

approach posited that self-knowledge de-rives from a process of taking the role

of the other in social inter-action. According to this view, the individual

internalizes norms and expectations of the social group (the generalized other)

in the course of social interaction. This internalization of the generalized

other provides the basis for self-reflection, including the capacity to

evaluate one’s gestures and deeds, and anticipate others’ responses to one’s

behavior. Social psychological inquiries into the self in the middle decades of

the 20th century were sparse, but over the past 20 years interest in

self-functioning has dramatically increased, in part spurred by social

cognition research (Taylor, 1998). While a comprehensive review of this now

voluminous literature is beyond the scope of this discussion, a sampling of

representative, contem-porary social psychological perspectives on self is

presented here

Social Psychological Models of Self

Consistent with trends toward systematic

examination and articulation of the person–environment relationship in

personality functioning as a whole (Baumeister, 1999; Curtis, 1991; Mitchell,

2000), social psychological models presume that self-functioning is influenced

both by intrapersonal and situational context factors (Baumeister, 1998; Tesser

et al., 2000). From this perspective,

self-functioning may be understood in terms of personal traits and dispositions

(individual self), interpersonal roles and relationship patterns (relational

self), and larger group identifica-tions (collective self) (Sedikides and

Brewer, 2001).

Investigations of the self have produced myriad

conceptu-alizations of self-functioning. To organize the diverse strands of

theory and research on self, Baumeister (1998) has proposed three dimensions

central to the construction of self, including reflex-ive consciousness,

interpersonal being and executive function. Reflexive consciousness refers to

the human capacity to reflect on personal thoughts, feelings and behavior, and

is the mechanism that makes possible the construction of self-conceptions and

self-knowledge. Interpersonal being connotes the relational com-ponent of self

that develops within ongoing interpersonal trans-actions and serves the vital

psychological function of negotiating the relational world. Executive function

refers to the capacity for agency, decision-making and initiative in living,

and is the basis for active engagement with the environment. Social

psychologi-cal models of self-functioning typically presuppose and/or focus on

one or more of these dimensions of self.

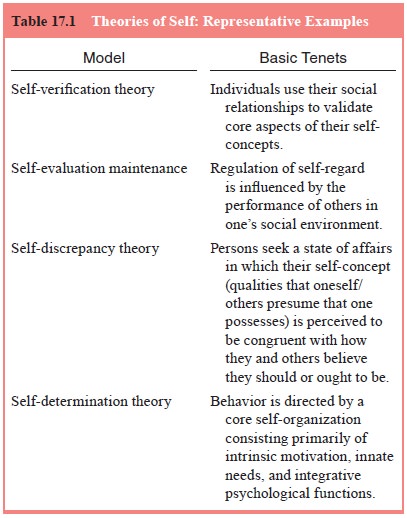

To illustrate current social psychological thinking

with regard to self-functioning, a few examples of recent social psychological

theories of self are outlined briefly in the table: the self-verification

theory, self-evaluation maintenance, self-discrepancy theory and

self-determination theory (Table 17.1). Each of these models represents a

significant contribution to the social psychological perspective on self, and

although not clinically derived, has significant relevance to the clinical

situation.

Self-presentation, Impression Management and Personal Identity

Along with specific theoretical models of self, social psychology has examined the impact of self-presentation and impression management on self-functioning. Specifically, people are invested in presenting themselves in certain ways (performing) in social situations and endeavor to control the impressions that others have of them in those situations (Goffman, 1959; Leary, 1995). These modes of self-presentation have some degree of influence on self-definition and personal identity (Tice and Baumeister, 2001). Successful impression management requires an awareness of social expectations regarding behavior in a specific situation, a desire to act within social expectations, and a capacity to present oneself in such a way that the desired impression is conveyed. One’s behavior in social interactions also is guided by the impressions one forms of others. Generally speaking, it is adaptive to be cognizant of others’ views of oneself and to portray oneself in particular ways because these interpersonal strategies can enhance one’s capacity to comprehend, regulate and anticipate social interaction patterns (Schlenker and Pontari, 2000). In deciding how to present them-selves in a social interchange, people stress the commonalities between themselves and what is expected of them and present a personally and socially desirable public image to assure social compatibility, solidarity with others and social approval.

Self in Health and Illness

Issues of physical health and illness influence

both one’s self-definition and the quality and nature of one’s interpersonal

world. In turn, one’s self-definition influences how one responds to

health-related concerns. Self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997), which connotes beliefs

regarding one’s capacity to perform a required action, is an especially

important variable in predicting individual responses to health-related

concerns (Salovey et al., 1998). To

heighten the extent to which individuals can exercise control over their own

health behaviors and associated environmental stresses, individuals may be

taught self-management and self-control tech-niques. Learning the array of

cognitive and behavioral coping strategies that increase people’s ability to

manage their illness and associated affective responses also enhances

self-efficacy and overall capacity for effective self-regulation.

Mental Health Implications

Mental health professionals increasingly have

appreciated the need to understand self-functioning in a relational context.

This shift in focus has been influenced by attachment theory (Bowlby, 1982),

interpersonal psychiatry (Sullivan, 1953), psychoanalytic object relations

theory (Greenberg and Mitchell, 1983), feminism (Jordan, 1997) and family

systems theory (Gurman and Kniskern, 1981, 1991). For example, Sullivan’s

(1953) clinical theory included a characterization of the self-system as

composed of the good-me bad-me and not-me personifications, with the

self-system defined interpersonally on the basis of perceived responses of

significant others beginning early in life. Within the psychoanalytic

tradition, adherents to object relations theory (Fairbairn, 1954; Guntrip,

1969; Winnicott, 1965), self-psychology (Kohut, 1977), and relational

psychoanalysis (Mitchell, 2000) have underscored the importance of the

interpersonal contributions to self-development and functioning. Each of these

approaches emphasizes that the nature and quality of the relationship between

the therapist and patient is centrally relevant to helping the patient make

changes in self-functioning.

Models of Self and Clinical Intervention

Based on a synthesis of theoretical models and

empirical research findings, Deaux (1992) has developed a social psychological

model of relationships between self and mental health that re-volves around

self-definition and the impact of challenges to self-definition on mental

health functioning. In the model, self-definition is conceptualized as

consisting of 1) specific domains of functioning (e.g., social and personal

identities, life tasks) rather than as a global entity; 2) goals and

aspirations as mo-tivational elements; and 3) active interpretations of

experience and personal meaning constructions. Demographic and socio-cultural

variables, social structure and socialization processes are viewed as distal

influences on self-definition. Although the self-definition is presumed to be

relatively stable, it is subject to challenge by internal factors (e.g.,

perceived discrepancies between the self-definition and internally defined

expectations for oneself, negative social comparisons) and/or external factors (e.g.,

illness, change of employment status, changes in significant relationships).

Challenge triggers a self-evaluation process to deal with information that is

inconsistent with one’s predominant self-definition. Self-evaluation results in

regulation and recon-struction activities focused internally on the self (e.g.,

self-esteem maintenance, self-affirmation, self-esteem protection, activities

associated with alterations in self-definition) and/or externally on the

external world (e.g., self-verification, self-monitoring, behavioral

disconfirmation activities associated with presen-tation of the reformulated

self-definition in the social world). Negative outcomes of the self-evaluation

process are presumed in the model to be associated with adverse mental health

outcomes.

Drawing from myriad theories and concepts from

within social psychology, Deaux’s (1992) model acknowledges the cen-trality of

self-regulation processes in the maintenance of overall mental health as

individuals respond to challenges to existing self-definitions. Self-regulation

processes are a core element of the social psychological theories of self

summarized herein, including self-verification theory (Swann, 1983, 1997),

self-evaluation main-tenance (Tesser, 1991; Beach and Tesser, 1995),

self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987; Moretti and Higgins, 1999) and

self-de-termination theory (Deci and Ryan, 2000; Ryan and Deci, 2000). Each of

these models provides insights for the clinical under-standing and treatment of

mental health problems as they relate to challenges to self-definition and the

self-evaluation processes that ensue in response to such challenges. Examples

of the clini-cal relevance and utility of these models for clinical work now

will be considered.

Self-presentation and Impression Management in Clinical Perspective

While the maintenance of a specific social image

through impression management can yield psychological benefit, certain patterns

of self-presentation can also have a negative psychological impact. For

example, preoccupation with presenting oneself as competent in a particular

pursuit when realistic appraisal sug-gests otherwise can give rise to pursuit

of goals for which one is not suited, generating impractical expectations for

self and precipitating associated frustration and disappointment. Extreme

efforts to present oneself in a particular light can lead to maladap-tive

states of mind, response patterns and relationships (Shepperd and Kwavnick,

1999).

Impression management also has implications for the

self-relevant social emotions of guilt and shame. Both guilt and shame are

responses to perceived transgressions on the part of the self, but differ in

that guilt involves condemnation of a particular behavior and is accompanied by

remorse or regret, whereas shame involves condemnation of one’s self and is

ac-companied by feelings of being exposed as objectionable and bad (Tangney and

Salovey, 1999). Both guilt and shame are emotional experiences tied to one’s

perceived failure to maintain a positive self-presentation, and each propels

specific patterns of impres-sion management. For instance, guilt tends to spark

interpersonal efforts to make reparation for one’s behavior, whereas shame may

prompt social avoidance associated with a wish to hide the self from view

(Tangney and Salovey, 1999). Although guilt and shame are expectable emotional

dimensions of everyday psycho-logical life, their problematic manifestations

can adversely affect both self-regulation and interpersonal relationships, and

there-fore must be considered in clinical evaluation and treatment of

psychological dysfunction.

Related Topics