Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Social Psychology

Social Psychology: Interpersonal Processes: Attachment

Interpersonal Processes

Recent multidisciplinary trends in theory and research

on in-terpersonal phenomena have converged in scientific efforts to elucidate

relationship dynamics, including their antecedents and consequences (Reis et al., 2000). Underlying these efforts

is the assumption that, since human behavior takes place within a relational

context, a comprehensive scientific understanding of human behavior requires

careful study of interpersonal relation-ships (Reis et al., 2000). Although there have been differences of opinion

regarding how to define the term relationship, there is loose agreement that a

relationship involves an interaction be-tween relational partners that affects

the subsequent behavior of each partner in the interaction (Berscheid and Reis,

1998).

The study of interpersonal relationships spans a

multitude of behavioral domains relevant to social psychology. Although

recognition of the limits of the traditional individualistic focus of social

psychological theory and research recently has prompted calls for a more

systemic conceptual approach to research on in-terpersonal relationships, the

vast majority of work to date has examined relationships between individual

variables and rela-tionship experiences (Reis et al., 2000). It is important to empha-size that the nature and

qualities of human social interaction are not attributable solely to

evolutionary and biological influences and processes and are not directly

parallel to animal behavior (Hinde, 1987). Further, while an evolutionary

perspective can provide useful insights, adoption of such a viewpoint does not

imply strict genetic determinism or unmodifiability of evolved behavioral

patterns (Buss and Kenrick, 1998).

Attachment

Bowlby (1982) regarded attachment between infants

and caregiv-ers as an innate relational pattern that evolved in order to ensure

the survival of the infant. Attachment phenomena are common in birds and

mammals, with extended dependency periods in which offspring are fed, cleaned,

sheltered and protected by the parent. In many species, attachment is enhanced

by imprinting (Lorenz, 1970), a learned attachment that forms at the earliest

phases of development. Imprinting is most likely to occur dur-ing specific,

critical periods of development. If imprinting is not achieved during those

times, it is difficult to attain. Attachment facilitates survival of the

offspring, and investment in parental care for offspring is theorized to

involve a cost–benefit trade off; the increased likelihood that offspring will

survive is weighed against potential costs of parental care.

Attachment theory has as its cornerstone a system

of recip-rocal interactions that facilitate psychological safety and security

(i.e., attachment behavioral system) (Bowlby, 1973, 1980, 1982). According to

Bowlby’s theory of attachment, as a consequence of evolutionary processes,

children possess emotional and behavio-ral systems that organize and direct

them to seek proximity and to bond with their primary caretakers when they feel

distressed or threatened. The nature and quality of parental response in such

instances influences the child’s development. Children’s internal working

models of the attachment figure and the self in relation to this figure (i.e.,

self- and object-representations and schemas of interaction patterns between

self and attachment figures) influ-ence their attachment style and the quality

of their interpersonal relationships (Bretherton and Munholland, 1999).

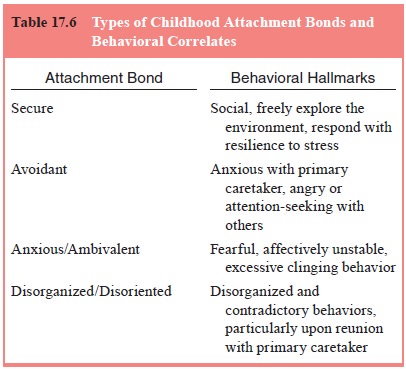

The bulk of attachment research has been conducted

with young children and their primary caretakers. This research reveals four

attachment bonds types (i.e., secure, avoidant, anxious/ambivalent,

disorganized/disoriented) most noted when

infants and their primary caretaker are reunited

following a brief, experimentally controlled separation (Ainsworth et al., 1978; Hesse and Main, 2000;

Main, 2000) (Table 17.6).

Securely attached children are social, able to

explore their environment freely, and resilient when faced with stressful

situa-tions. In contrast, avoidant children tend to be anxious with their

primary caretaker(s) and angry or attention-seeking with others.

Anxious/ambivalent children typically are fearful of the envi-ronment,

affectively unstable, and cling inordinately to others. Finally, disorganized/disoriented

children often exhibit signs of disorganization and contradictory behaviors,

particularly upon reunion with their primary caretaker. Longitudinal research

shows that attachment behavior patterns are stable over time, predictive of

school behavior and peer interactions, and consist-ent with the quality of

parenting received and parental attach-ment style (Bowlby, 1988; Sroufe, 2002;

Sroufe et al., 1990).

Adult Attachment

Recently, clinicians and researchers have begun to

turn their attention to attachment patterns in adults (Sperling and Berman,

1994; West and Sheldon-Keller, 1994). Similar to infant attachment patterns,

adult attachment is presumed to be rooted in evolutionarily significant

biological adaptation processes (Hazan and Diamond, 2000) and is characterized

by a strong interest in the other, a desire to remain physically close to and

spend time with the other, reliance on ongoing access to the other, dependence upon

the other for support in the face of physical or emotional threats, and

feelings of discomfort and distress upon separation (Feeney, 1999; Shaver and

Hazan, 1993; West and Sheldon-Keller, 1994). However, unlike attachment

patterns in children, the primary adult attachment objects typically are peers,

adult patterns of relating are more reciprocal, and attachment figures often

also are sexual partners (Feeney et al.,

2000). Adult attachment is influenced significantly by working models of the

attachment object and self that have their origins in childhood attachment

experiences with primary caretakers (Bartholomew and Horowitz, 1991). Work in

adult attachment theory addresses the establishment and maintenance of primary

emotional partnerships in adult life, the effects of early and current

attachment experiences on the development of psychopathology, and the use of

attachment theory to guide therapeutic interventions.

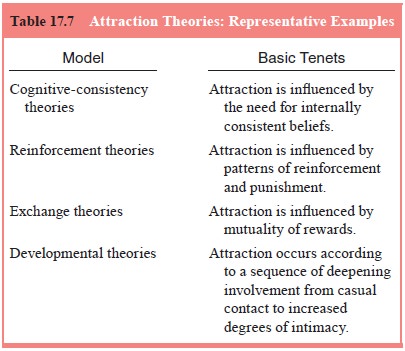

Among the most compelling questions in research on

close relationships are those that pertain to relationship sat-isfaction and

stability. Work in this area has been influenced (see Table 17.7) heavily by

the social exchange tradition, which assumes that the exchange of rewards and

costs is a key influ-ence on relationships (Berscheid and Reis, 1998).

Specifically, social exchange theory suggests that people are motivated to

maximize rewards and minimize costs, with the favorability of relational

outcomes being defined by the relative balance of rewards and costs for each

relationship participant. Within the social exchange framework, interdependence

theory (Thibaut and Kelley, 1959; Rusbult and Van Lange, 1996) has been

especially useful in making predictions about relationship satisfaction and

stability. This model posits that people evalu-ate relationship satisfaction

according to expectancy standards for relationship outcomes (comparison level),

and that relation-ship satisfaction is a function of the extent to which

outcomes meet or exceed these expectancy standards. The model also posits an

additional evaluative standard employed by individu-als to determine whether or

not to stay in a given relationship (comparison level for alternatives). This

standard is relevant to predicting relationship stability, as it represents the

mini-mal acceptable relationship outcome level for remaining in a given

relationship when outcomes associated with available alternative relationships

are taken into consideration. Accord-ing to the model, therefore, relationship

stability is related to the combined influence of relationship attractiveness

and the availability of desirable alternatives external to the relation-ship.

Relationship stability is likely to be compromised to the extent that

relationship attractiveness is lower than the appeal of available relationship

alternatives. In general, relation-ship stability is influenced by degree of

commitment to the relationship, availability in the social environment of

viable re-lationship alternatives, perceived approval for the relationship by

the social networks of the respective partners, and partner perceptions of the

relative equity/inequity in gains as a result of being in the relationship

(Berscheid and Reis, 1998).

Sexual behavior is an important channel of

expression in certain types of interpersonal relationships (e.g., romantic

relationships) and its patterns of expression may symbolize underlying

relational dynamics (Mason, 1991). While some social psychological perspectives

have explored sexuality as it relates to romantic love, much of the extant theory

and research related to sexuality has focused on mate selection (Berscheid and

Reis, 1998). Evolutionary psychology, in particular, has exam-ined mate

selection in detail (Buss and Kenrick, 1998).

In humans, sexual behavior serves more than the

purely biological functions of procreation and physiological release, as it is

also an important means of expressing love, closeness and the need for human

contact. Sexual behavior is manifested in diverse ways determined by a complex

interplay among one’s relationships, life situations and the broad

sociocultural context. Although normative sexual behavior has received

systematic em-pirical study, beginning with the survey research of Kinsey and

colleagues (1948, 1953) and continuing to the present day (Janus and Janus,

1994), much of the emphasis of psychological research has been on sexual

dysfunction and its treatment (Kaplan, 1974; Masters and Johnson, 1970).

Considerable evidence has accrued that social integration in general, and social support in particular, are related both to en-hanced health and lowered risk of mortality (Berscheid and Reis, 1998; Stroebe and Stroebe, 1996). Both main effect models and stress-buffering models have been employed to explain observed relationships between social support and health factors (Stroebe and Stroebe, 1996). Main effect models assume that a specific factor, such as social influence, may directly affect health and well-being via its impact on health beliefs, attitudes and behav-ior. By contrast, stress-buffering models presume that social sup-port confers health benefits only to the extent that an individual is experiencing stress. According to this perspective, social support may provide health benefits indirectly by serving as a resource to help the individual cope with health-related stress.

Several factors influence the likelihood of

social-support provision. Among these are social-exchange processes and so-cial

norms surrounding provision of help for individuals in ill-health, as well as

causal attributions made about the recipient of social support (Stroebe and

Stroebe, 1996). For example, social psychological research suggests that a

curvilinear relationship exists between degree of distress and likelihood of an

individual receiving social support, with moderate distress eliciting the

greatest degree of supportive actions by others. Further, indi-viduals

perceived by others as responsible for their plight may be less likely to

receive social support than those whose ill-health is perceived by others as

caused by uncontrollable circumstances. Additionally, social support may be

withheld if individuals are perceived as not trying hard enough to manage their

illness or are not showing sufficient improvement in response to social support

provision. These patterns may have unfortunate implications for individuals

with disease syndromes that cause high stress levels, are highly stigmatized,

and/or are chronic or progressive, as they may find themselves socially

isolated at times of high need for social contact.

As has already been mentioned, there is a vast

scientific literature in support of the idea that relationships contribute both

to physical and mental well-being (Berscheid and Reis, 1998; Reis et al., 2000; Stroebe and Stroebe,

1996). This em-pirical base complements the widespread clinical regard for the

treatment relationship as a primary tool of influence and thera-peutic change

(Mitchell, 2000). As such, social psychological theory and research on

relationships can contribute substan-tively to current thinking about how to

structure the clini-cian–patient relationship to maximize mental health

treatment benefit (Derlega et al.,

1991).

Related Topics