Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Psychoanalytic Theories

Psychoanalytic Theories: Development and Major Concepts

Development and Major Concepts

Freud’s Contributions

Dreams

Freud’s study (1900, 1901) of dreams during his

self-analysis and in his work with patients resulted in an elaborate

understanding of the workings of the mind. The analysis of dreams continues to

hold a prominent position in psychoanalytic practice. Dreams give expression to

unconscious wishes in disguised form and generally represent their fulfillment

or gratification. Analysis of dreams can provide conscious access to

unconscious drives, wishes, fantasies and associated repressed infantile

memories, providing what Freud called the “royal road to the unconscious”.

The dream that is remembered on awakening is

referred to as the manifest dream.

Its component elements include sensory stim-uli occurring during sleep, the day residue and the latent dream content. The day residue consists of experiences of events of the preceding day or days, often

associated in the mind with uncon-scious wishes. The latent dream content is

the set of unconscious infantile urges, wishes, and fantasies that seek

gratification during the dreaming state of blocked motor discharge and regression.

Freud hypothesized a dream censor whose function is to keep the unconscious latent

content from conscious awareness, thereby preventing the emergence of anxiety

and awakening from sleep. The surreal and fantastic quality of the remembered

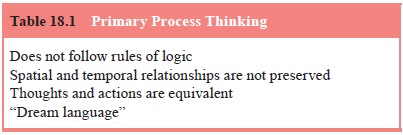

manifest dream is a reflection of the influence of dream work and primary

process unconscious mentation (Table 18.1): depic-tion of immediate

gratifications, absence of the rules of logic of conscious thought, merging of

past and present, absence of nega-tives, loss of distinction between opposites

and representation of a whole by a part. The activity of the dream work

involves a set of mental mechanisms designed to disguise and distort the latent

content in keeping with the function of the dream censor

In psychoanalytic treatment, the analysis of dreams

attempts to take this process backward, starting with the patient’s narration

of the dream and then observing the patient’s associa-tions to the manifest

elements, with the goal of obtaining insight into the dreamer’s unconscious

wishes, memories and infantile fantasies, and processes of defense.

Childhood Sexuality

In his analyses of adult patients and observations

of children, Freud (1905) became convinced of the influence of early sexual

fantasies on the formation of neurotic symptoms and of the univer-sality of

sexual wishes throughout life including early childhood. The term sexuality is used in this context to

refer not exclusively to adult genital sexuality but to a variety of body

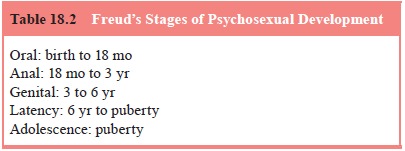

stimulations that are pleasurable and sensually gratifying. He postulated a

devel-opmental sequence of body zones that become primary foci of erotic

sensations and mental organization (Table 18.2): oral, anal (including perianal

and urethral) and genital (phallic). During de-velopment, there is a more or

less orderly progression from one zone to the next, with pleasure being derived

from sucking, biting, tasting, touching, looking, smelling, filling, emptying,

penetrating and being penetrated. In the neuroses, the repressed component

instincts become an unconscious source of symptom formation.

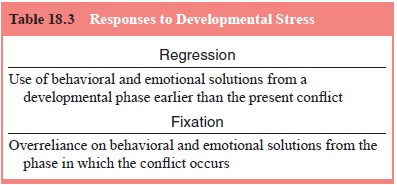

Fixation (Table

18.3) at a particular phase of development

may occur if there is insufficient mastery of issues pertinent to that

phase. Fixations result in continued manifestations of phase specific issues in

a person’s behavior, influencing later person-ality adjustment (e.g., the anal

organization of the obsessional character). Regression (Table 18.3), a return to a less mature level

of mental organization, may occur in the context of

stressors or conflict that overtaxes the adaptive capacities of an individual.

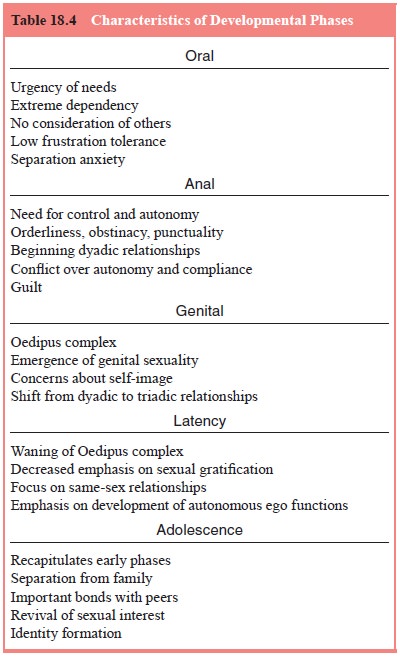

The first of the phases described by Freud is the oral phase (Table 18.4), which encompasses approximately the first 18 months of life. During this phase, the mouth, lips and tongue

are the primary sources of sensual gratification. The activities of sucking,

swallowing, mouthing and biting, as well as the experi-ence of being held

during feeding, form a cognitive template for the organization of fantasy and relatedness

to others. The infant at this stage is dependent on mother for nurturance,

protection and sustenance. A favorable outcome of this stage is the

estab-lishment of a capacity to feel trust and safety in a dependent

relationship,

a sureness that needs will be recognized and grati-fied, and a minimum of

conflict about aggressive wishes oc-curring during moments of frustration.

Excessive neglect or deprivation during this period may result in adult

feelings of interpersonal insecurity, mistrust, envy, depression, excessive

dependency, anticipation of rejection by others and proneness to moments of

diffuse rage.

The anal phase (see Table 18.4) emerges

with the develop-ment of increasing neuromuscular control of the anal and

ure-thral sphincters and takes place from about 18 months to 3 years. Fantasy

organizes around anal pleasure and anal functions such as withholding,

expelling and controlling. Because of the child’s increased motor skills,

language development and emerging autonomy, she or he is expected to take more

of an active part in self-care activities, including using the toilet. Related

to toi-leting, power struggles may ensue around the child’s soiling or

withholding. Anger is felt toward those in control of this educa-tive process,

but the child also wishes to please them. The child in the anal phase

experiences considerable ambivalence around expelling versus retaining (giving

versus keeping), obedience and submission versus defiance and protest, and

cleanliness and orderliness versus messiness. Fixation at this stage results in

a personality organized around anal erotism and its associated conflicts,

characterized by wishes to dominate and control peo-ple or life situations,

rigidity, defiance and anger toward author-ity, neatness, orderliness,

messiness, parsimony, frugality and obstinacy.

The phallic or phallic–oedipal or genital

phase (see Table 18.4) occurs from the ages of 3 to about 5 or 6 years. At

the onset of this period, sensual pleasure has become most highly focused

around the genitals, and masturbatory sensations more closely resemble the

usual sense of the word sexual. The

child at this time has become even more autonomous and has more so-phisticated

motor and language skills, conceptual capabilities and elaborate fantasies. The

child is better able to recognize feelings of love, hate, jealousy and fear;

has a more distinct recognition of the anatomical difference between the sexes;

and appreciates that the parents have an intimate sexual relationship from

which the child is excluded. Thinking about relatedness to others shifts from

the largely dyadic (mother–child) quality of the prephallic phases to an

appreciation of relational triangles.

Freud

recognized in his patients’ associations that there were regularly occurring

incestuous fantasies and wishes toward the parent of the opposite sex that were

involved in the forma-tion of neurotic difficulties. He termed this phenomenon

the Oedipus complex, in reference to

the story of Oedipus, who unknowingly

killed his father and married his mother. In the midst of the Oedipus complex,

the child wishes to possess exclu-sively the parent of the opposite sex and to

eliminate the parent of the same sex. The jealousy and murderous rage felt

toward the same-sex parent are accompanied by fears of retaliation and physical

harm. Because these fantasies are associatively linked to pleasurable genital

sensations, the child has specific uncon-scious fears of being castrated, which

Freud referred to as the castration

complex. The oedipal phase proceeds differently in boys and girls.

Successful

passage through the phallic phase includes resolution of the Oedipus complex

and repression of oedipal fan-tasies. The child internalizes the parental

prohibitions and moral values and demonstrates a greater capacity to channel

instinctual energies into constructive activities. Excessive conflict or

trau-matization during this phase may lead to a personality organized around

oedipal fantasies and conflicts or a proneness defensively to regress to anal

or oral organization.

During the latency

phase (see Table 18.4), from age 6 years to puberty, play and learning take

a prominent position in the child’s behavioral repertory as cognitive process

ma-tures further. Although Freud believed that the sexual urges become

relatively quiescent during this phase, observation indicates that they are

expressed in derivative form in the child’s play. At puberty and through

adolescence, genital urges once again predominate, but there is now a

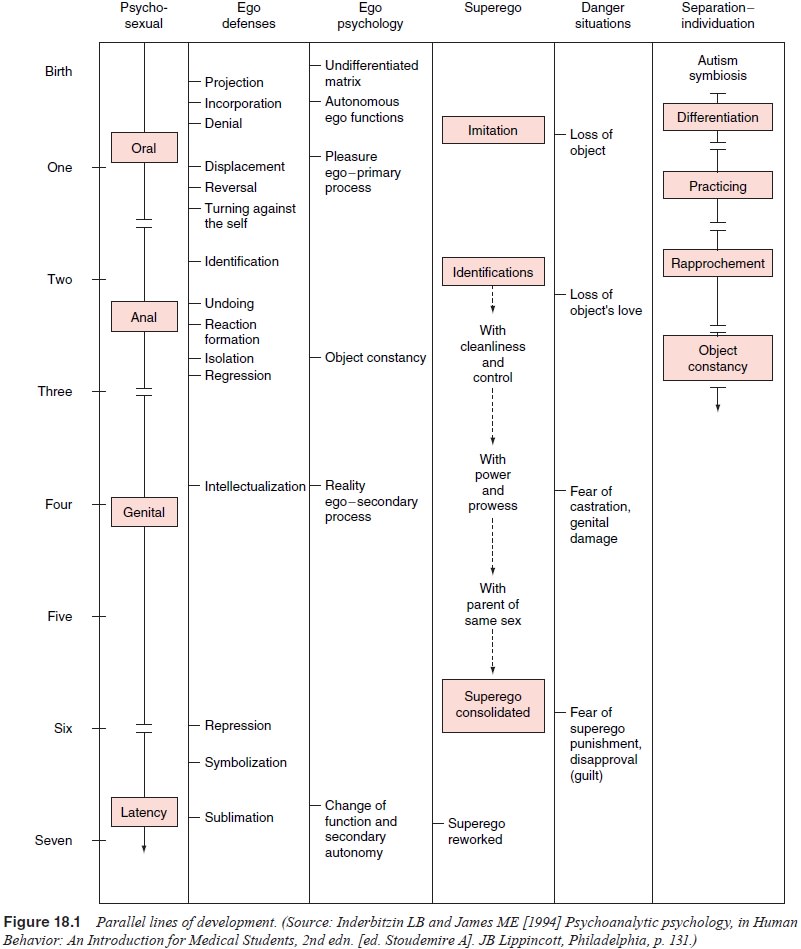

consolida-tion of sexual identity and a movement toward adult sexuality (Figure

18.1)

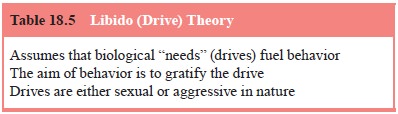

Libido Theory

Freud’s continued consideration of the sources and

nature of the sexual drives led to his dynamic model of the mind referred to as

libido

theory (Table 18.5). This theory attempted to explain the observation that behavior and mental activity are not only

trig-gered by external stimuli (as in the reflex arc) but also generated by

primary internal processes. Freud defined instinct as “a con-cept on the

frontier between the mental and the somatic, as the psychical representative of

the stimuli originating within the or-ganism and reaching the mind, as a

measure of the demand made upon the mind for work in consequences of its

connection with the body”. Regardless of the specifics of their origins,

derivatives of the instincts are experienced mentally as compelling urges and a

source of motivation.

Although Freud had given up the idea that sexual

trau-matization was always the cause of psychoneurotic symptoms, he maintained

the view that the sexual instinct played an etio-logical role in the neuroses

and that sexual stimulation exerted a predominant force on mental activity

throughout life. Freud termed this force libido.

The discharge of libido is experienced as pleasure; the welling up of libido

without discharge is felt as tension or unpleasure. According to the pleasure principle, the individual

seeks pleasure (through the discharge of libidinal tension) and avoids

unpleasure. The primary process quality of unconscious mentation follows the

pleasure principle as it maintains its focus on the gratification of wishes. As

the mind develops, conscious mentation becomes more governed by the reality principle (Freud, 1911)

involving a shift from fantasy to

perception of and action on reality. The secondary process form of conscious

thought follows the reality principle. Under the influence of the reality

principle, gratification of wishes may be delayed with the aim of eventually

achieving greater and/or safer pleasure.

The sexual instinct has four defining components: source, pressure (or impetus), aim, and object. Source refers

to the bio-logical substrate of the instinct. Pressure is the amount of force or “demand for work” of the

instinct. The aim is the action

designed to accomplish release of tension and satisfaction. An object is the target of desire, the

person or thing through which gratification is accomplished. Although the

libido theory has been criticized because it was based on 19th century German

scientism, it has served as a useful metaphor to understand pleasure,

attachments, and the dynamic processes of mental activity.

From the Topographical to the Structural Model

According to the topographical theory, three

regions or systems of the mind exist as defined by their relationship to

conscious thought: the conscious, preconscious and unconscious. The conscious mind registers sensations

from the outside world and from internal

processes, and is the agency of ordinary wakeful thought. Conscious mentation

follows the reality principle and uses secondary process logic. The preconscious includes mental contents

that can gain access into consciousness by the focus-ing of attention. The unconscious is defined from three basic

angles: descriptively, it consists of all mental processes and con-tents

operating outside conscious awareness; dynamically, these processes and

contents are kept actively repressed or censored by the expenditure of mental

energy to prevent the anxiety or repugnance that would accompany their

conscious recognition; and as a mental system, it is a part of the mind that

operates in accordance with the pleasure principle using primary process logic.

Over time, Freud encountered clinical phenomena

that were not adequately accounted for by the topographical model. Freud

revised his theory of mental systems to include the struc-tural model, but the

useful conception of the dynamic uncon-scious and the particular qualities of

conscious, preconscious and unconscious mentation have been retained.

Theory of Narcissism

In all mental functioning, it is possible to

observe the balance be-tween libido deployed toward objects and libido directed

toward the self. For example, when a person is in love, much libido is

at-tached to the loved object, even to the extent that the person feels himself

or herself diminished (from decreased ego libido). During physical illness or

hypochondriacal states, libido is pulled toward the ego so the person appears

preoccupied with the body and un-interested in the world. According to the

pleasure principle, the mind seeks to discharge libido, and if it is dammed up,

symptoms will result. In neurotic persons, excess object libido has accumu-lated

and, undischarged, produces anxiety. In psychotic persons, ego libido has been

prevented from being discharged outward, so it is discharged inward, resulting

in hypochondriacal anxiety and megalomania.

Internal judgmental processes and self-regard are

also ad-dressed by the theory of narcissism. In normal adults, most evi-dence

of the operation of ego libido has been repressed. A new target of self-love

has been constructed, the ego ideal,

a forerun-ner of the superego concept, consisting of ideas and wishes for how

one would like to be. Similarly, love objects may become the subject of

idealization. Freud theorized a separate psychic agency, which he called the

superego (see below), that attends to ensuring narcissistic satisfaction and

measuring self-reflection, censoring and repression. Living up to the ideal,

loving oneself and being loved, reflects attempts to restore a state comparable

to the primary narcissism of infancy.

Melancholia

In Mourning

and Melancholia Freud (1917), developed a theory to explain processes of

guilt, internal self-punishment and de-pression. To do this, he contrasted

states of grief or mourning with the condition of melancholia, now called

depression. Both have in common the experience of pain and sadness, and both

are brought on by the experience of loss, but the person in mourning maintains

her or his positive self-regard, whereas the person with melancholia feels

dejected, loses interest in the world, shows a di-minished capacity to love,

inhibits all activities and exhibits low self-regard in the form of

self-reproaches. In mourning, libido is gradually withdrawn from the object

attachment; in melancho-lia, the ego feels depleted or comes under attack as

though “one part of the ego sets itself over against the other, judges it

criti-cally, and as it were, takes it as its object”. This critical agency

(again a theoretical forerunner of the superego) comes to operate independently

of the ego.

The self-accusations of the person with melancholia seem to fit best with criticism that might be leveled against the lost object. In the case of suicidal impulses, the melancholic person seems to be directing at himself or herself the sadism and mur-derous wishes felt toward the disappointing or lost other. Freud theorized that in the context of the loss of an ambivalently held object, the ego incorporates, or forms a narcissistic identifica-tion with, the object. Hostility originally felt toward the object is now directed at the self, giving rise to feelings of torment, suffering and self-debasement. A predisposition to melancholia may thus result from forming narcissistic object attachments and identifications.

Dual-instinct Theory

Freud had originally considered two types of

instincts, the sexual and the ego (self-preservative) instincts, and considered

sadism to represent a fusion of the two, with hostility occurring in the

context of frustrated libidinal strivings. However, this theory did not

adequately address psychological situations in which destructive tendencies

seem to be operating independently of li-bidinal or self-preservative drives.

Freud concluded that there must be a separate

instinct of aggression, whose aim is destructiveness. The aggressive drive is

at work in impulses to harm, in the desire for control and power, in sadistic

or masochistic behaviors, in guilt and depression, and in the persecutory fears

of paranoid individuals.

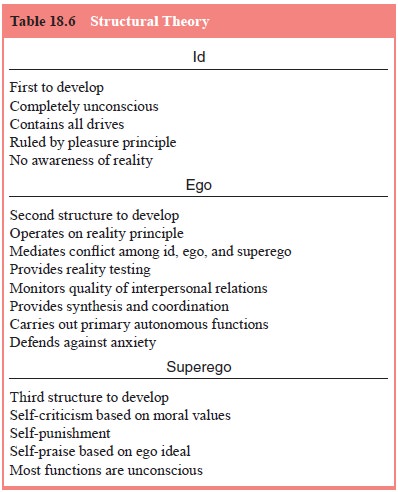

Structural Model

On the basis of the preceding considerations, Freud

revised his theory of the mind into what is now known as the structural or

tripartite model (Table 18.6). He conceived of three mental agen-cies operating

in the psyche: the id, the ego and the superego. The id is the biological source of instinctual drives, operating

uncon-sciously and following the pleasure principle. The activity of the

id generates the motivational push for

gratification of sexual and aggressive wishes.

The ego

grows out of the id early in human development. Its functions include

perception, interpretation of perceptions, voluntary movement, modulation of

affects and impulses, cog-nition, memory, judgment and adaptation to reality.

Subject to conflicting forces from the id, the superego and reality, the ego

synthesizes mental compromises that provide gratification of instinctual wishes

in accord with reality considerations and the moral demands of the superego.

The superego,

which develops as an outgrowth of both the ego and id, consists of the moral

standards, values and pro-hibitions that have been internalized throughout

childhood and adolescence. It is the source of internal punishment, which is

felt as guilt, and of internal reward. Early in development, the su-perego has

a harsh and archaic quality. During maturation under optimal conditions, it

becomes less harsh and comes to include loving components as well. In the

structural model, the ego ideal (discussed earlier) is considered a component

of the superego, accounting for feelings of shame and pride.

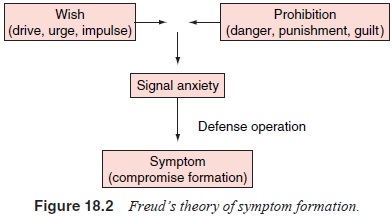

Anxiety and Symptom Formation

With the elaboration of the structural theory,

Freud progres-sively viewed the nature of anxiety and the origin of symptoms

(Figure 18.2) differently. According to his original theory, anxiety resulted

from the accumulation of undischarged sexual tensions caused by inadequate

sexual activity in the actual neu-roses or by inhibitions due to repression in

the psychoneuroses. Later, it became clear that anxiety was more closely

related to fear occurring in response to perceived dangers, either external or

internal. This led to a focus on the ego, one of whose functions is to

anticipate and negotiate danger situations. A dangerous or traumatic situation

is one in which excessive stimulation threat-ens to overwhelm the ego’s

capacity for delay and compromise.

The ego has as one of its tasks the continual

formation of compromises among id

wishes, the prohibitions and moral standards of the superego, and the dictates

of reality. If these

compromises are successful, anxiety will operate

predominantly on a signal level and behavior will be both sufficiently

gratifying and acceptable in reality. A symptom

neurosis occurs if these compromises are felt as uncomfortable, painful, or

maladaptive.

Post-freudian Ego Psychology

Ego, Defense and Adaptation

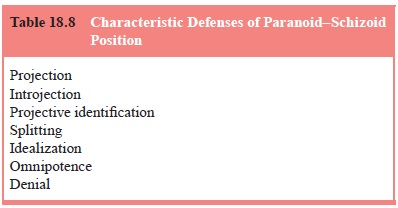

Anna Freud laid out a categorization of defense

mechanisms (1936) (Table 18.8). In discussing the preliminary stages of

de-fense that are first used by the ego to avoid pain from the external world,

she succeeded in integrating two main themes in the de-velopment of the ego

concept: defense and relations with external reality. Anna Freud advocated a

shift of the analyst’s attention to the ego as the proper field for

observation, in order to gain a picture of its functioning in relation to the

other two psychic structures, id and

superego. This more detailed

methodical at-tention to the mind’s surface, which includes manifestations of

unconscious ego activities, provides a much clearer view of the actual workings

of the mind. Her recommendation that the analyst listen from a point

equidistant from id, ego and superego emphasized the importance of observing

neutrally the influence of all three psychic agencies. The ego wards off not

only deriv-atives of instinctual drives but also affects that are intimately connected with the drives. She

advocated that priority be given to the interpretation of the defenses against

affects, as well as defenses against instinctual drives.

Related Topics