Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Psychoanalytic Theories

Psychoanalytic Theories: Heinz Kohut: Self-psychology

Heinz Kohut: Self-psychology

Conceptual Background

Freud and his followers tried to understand

psychological life in terms of biology. Their ideal was scientific objectivity.

They be-lieved the analyst’s human tendency to identify with the subjects of

study impeded objectivity. In contrast, Kohut viewed empathic comprehension as

the fundamental mode of psychoanalytic in-vestigation. It is the knowledge of

the other’s experience, what it is like to be in that person’s shoes. Empathy

is the understand-ing of another’s complex psychological experience as whole.

Using this empathic method, Kohut attempted to create an “experience-near”

psychology, explaining psychological events in terms of meanings and motives

comprehensible from ordinary experience. He contrasted this to Freudian

metapsychology with its postulated experience-distant forces, energies and

structures.

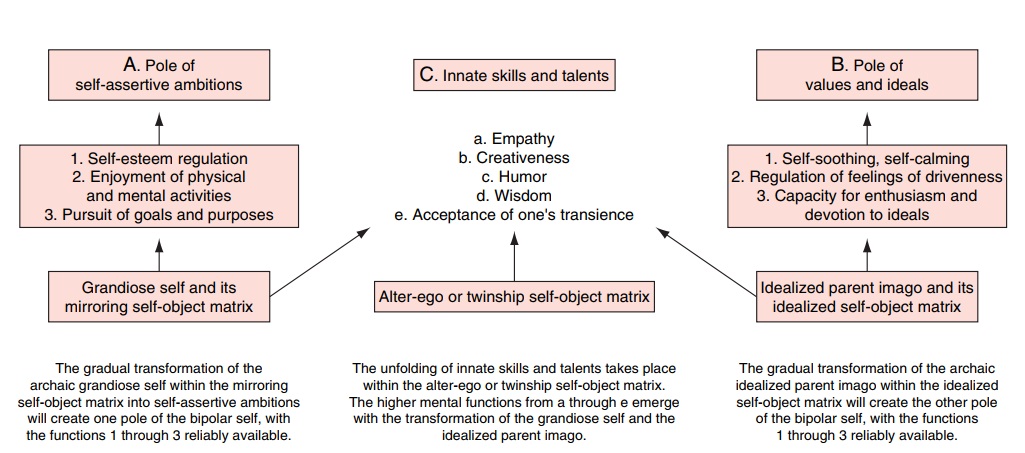

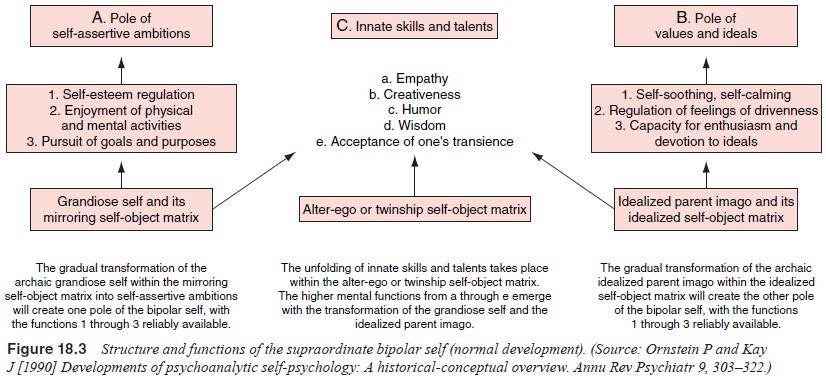

The concept of bipolar

self (Figure 18.3) refers to Kohut’s metaphorical description of the self

as having two poles, one of ideals and ambitions, the other a sense of the

grandiose self. The former involves the sense of being vigorous and coherent

because one is associated with what is good and powerful, for example, that an

adult might have when working in accord with professional ideals. The grandiose

pole of the self consists in the sense of being personally valuable and

appreciated, as a child may feel by virtue of the glowing enthusiasm of

parents.

Kohut’s singular contribution was the idea of the self-object. Clinical observations led

him to believe, like of ob-ject relations theorists, that the self could

survive and prosper only in the context of experience with others. These

experiences Kohut called self-objects, that is, objects (in the psychoanalytic

sense of intrapsychic representation of other people) that are necessary for

the well-being of the self. Kohut was speaking of intrapsychic experiences, not

interpersonal relations. Intrapsy-chic experience may be contingent on

interpersonal events. For example, the sense that one is appreciatively

responded to usu-ally requires some sort of active response from another

person, but how that person’s actions are experienced depends on many factors

besides the actions themselves.

Kohut (1971) described two main types of

self-object. Idealized self-objects embody

what is admirable, strong and vigorous.

The self feels alive and coherent by virtue of proxim-ity to the idealized

self-object. The youngster who feels like “a chip off the old block”, the

student who is enlivened in the pres-ence of a brilliant teacher, and the

religious person who feels safe in God’s presence have idealized self-object

experiences. Mirroring self-objects contribute

to the sense through their support

of the grandiose pole of the self. Kohut described three major types of

mirroring self-object:

· In merger, the self is maintained through

the sense that the person and self-object form a unity that is powerful and

alive in a way the person could not be by himself or herself. The sense of

merger can be found in the feeling that “we” do some-thing. Outside the

analytical situation, it is commonly seen in athletic, professional, and

military activities.

· Alter ego (or twinship) self-object induces a sense of personal coherence by virtue of having a partner who is like oneself.

· The mirroring self-object proper supports

the sense of per-sonal value and coherence through its accurate, valuing

ap-preciation of the person. The person who feels valuable and whole when a

parent’s or friend’s eyes light up as she or he comes into a room or who feels

similarly in response to au-thentic praise of accomplishment is experiencing

such a mir-roring self-object.

Self-objects remain essential throughout life.

Contrary to psychoanalytic theories that characterize maturity in terms of

au-tonomy, self-psychology views mature people as ordinarily depend-ent on

others for appreciation, comradeship, meaning and solace. The nature of the

people and institutions that embody self-objects changes with maturation. They

become more numerous and more complex, often serving many psychological functions

beyond their self-object function. It refers to the total experience of people

and institutions that sustain and support the development of the self.

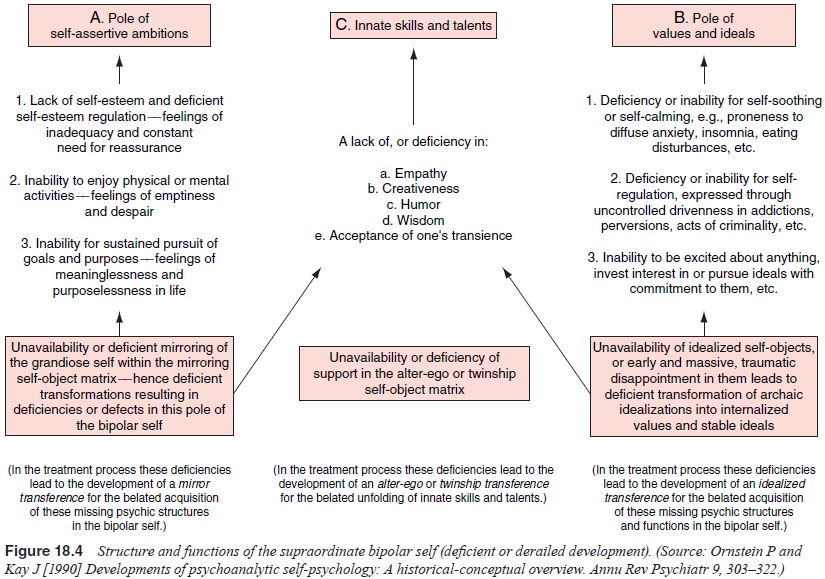

Disorders of the Self

The study

of self-psychology began with the realization that many symptoms of

psychological distress could be understood as arising from disorders of the

self. These include symptoms in-volving direct experiences of an endangered,

enfeebled, or frag-mented self, and symptoms arising from unsatisfactory

attempts to protect an endangered self. In practice, these symptoms may appear

in the same patient, but for expository purposes, separat-ing them is useful.

Sometimes the symptoms of self-pathology are acute (Figure 18.4), but more

often they are chronic states whose intensity varies as the self is felt to be

more or less in danger.

Symptoms

that directly express the enfeeblement or frag-mentation of the self include

certain depressive states, traumatic states, hypochondriasis, some forms of

rage, called narcissistic rage, and direct experiences of profound

disorganization.

A common

response to feeling the self-endangered is rage (Kohut, 1972). Narcissistic

rage is a major public health prob-lem. The most common cause of violence and

homicide is the rage engendered when people feel “disrespected”. Spousal

mur-ders most commonly result when an already demoralized person is confronted

by apparently trivial inconsiderate behavior and responds with murderous rage.

Communal chronic narcissistic rage may be a major factor in world history when

maintaining group dignity or seeking compensation for past inequities may lead

to hatred and destructiveness lasting for centuries. Narcis-sistic rage varies

from the momentary fury to lifelong states. Like many activities in the service

of the self, narcissistic rage is often rationalized. Perpetrators often

describe violence as necessary to achieve a goal but closer examination usually

shows that vio-lence does little to effect its supposed aim. Physical child

abuse, often a manifestation of narcissistic rage resulting from a sense of

inadequacy in caring for children, is commonly rationalized as “educating” the

youngster. Narcissistic rage often joins other psychological action designed to

invigorate the self.

States

involving the direct experience of fragmentation, in which patients cannot

organize experience or recognize their coherent wishes, are overwhelmingly

distressing. Any solution to this state, including the psychotic reorganization

of experience, feels better. Indeed, such states are most commonly seen briefly

with the onset of overt psychosis. Patients commonly describe this state as

“going crazy” and may attempt desperately to hang on to some organizing

principle. These states are psychiatric emergencies because many patients

report that death is prefer-able to the continuation of the intense anxiety

they experience. Many other symptoms are understandable as attempts to repair

an impaired or endangered self. These include relations with oth-ers designed

to achieve urgently needed self-object experiences and activities designed to

soothe or stimulate the self.

When

self-object functions become unavailable to such an extent that the person

cannot provide for himself or herself these functions based upon personal

abilities and memories al-ready available, a psychological emergency ensues. In

this cir-cumstance, the person uses less broadly adaptive means to try to

compensate for the missing but needed psychological functions. Pathological

functioning is manifested either in direct expression of a distressed self or

as problematic compensatory activities.

Intersubjectivity

Intersubjectivity

in psychoanalysis refers to the dynamic in-terplay between the analyst’s and

the patient’s subjective expe-riences in the clinical situation. To some

extent, all schools of psychoanalysis agree on the significance of

intersubjectivity in psychoanalytic work. Intersubjectivity embodies the notion

that the very formation of the therapeutic process is derived from an

inextricably intertwined mixture of the clinical participants’ subjective

reactions to one another. Knowledge of the patient’s psychology is considered

contextual and idiosyncratic to the par-ticular clinical interaction. This

interaction nexus is considered the primary force of the psychoanalytic

treatment process.

The

intersubjective position is that mental phenomena cannot be sufficiently

understood if approached as an entity that exists within the patient’s mind, conceptually

isolated from the social matrix from which it emerges. Intersubjectiv-ists see

the analyst and the patient together constructing the clinical data from the

interaction of both members’ particular psychic qualities and subjective

realities. The analyst’s per-ceptions of the patient’s psychology are always

shaped by the analyst’s subjectivity. Conversely, the patient’s psychology is

not conceptualized as something discoverable by the external, unbiased observer

(Hoffman, 1991; Ogden 1992a, 1992b, 1994; Spezzano, 1993

Related Topics