Chapter: Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing : Neurobiologic Theories and Psychopharmacology

Side Effects - Psychopharmacology

Side Effects

Extrapyramidal Side Effects. Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), serious neurologic symptoms, are the major side effects of antipsychotic drugs. They

include acute dysto-nia, pseudoparkinsonism, and akathisia. Although often

collectively referred to as EPS, each of these reactions has distinct features.

One client can experience all the reactions in the same course of therapy,

which makes distinguishing among them difficult. Blockade of D2 receptors in

the midbrain region of the brain stem is responsible for the development of

EPS. Conventional antipsychotic drugs cause a greater incidence of EPS than do

atypical antipsychotic drugs, with ziprasidone (Geodon) rarely causing EPS

(Daniel, Copeland, & Tamminga, 2006).

Therapies for acute dystonia, pseudoparkinsonism, and akathisia are

similar and include lowering the dosage of the antipsychotic, changing to a

different antipsychotic, or administering anticholinergic medication

(discussion to follow). Whereas anticholinergic drugs also produce side

effects, atypical antipsychotic medications are often pre-scribed because the

incidence of EPS side effects associ-ated with them is decreased.

Acute dystonia includes

acute muscular rigidity and cramping, a stiff or thick tongue with difficulty

swallow-ing, and, in severe cases, laryngospasm and respiratory dif-ficulties.

Dystonia is most likely to occur in the first week of treatment, in clients

younger than 40 years, in males, and in those receiving high-potency drugs such

as halo-peridol and thiothixene. Spasms or stiffness in muscle groups can

produce torticollis (twisted head and

neck), opisthotonus (tightness in the

entire body with the head back and an

arched neck), or oculogyric crisis

(eyes rolled back in a locked position). Acute dystonic reactions can be

painful and frightening for the client. Immediate treatment with

anticholinergic drugs, such as intramuscular benztro-pine mesylate (Cogentin)

or intramuscular or intravenous diphenhydramine (Benadryl), usually brings

rapid relief.

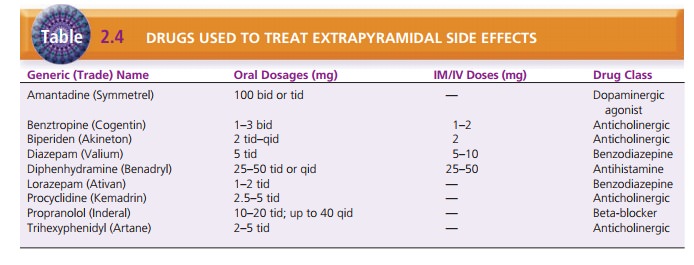

Table 2.4 lists the drugs, and their routes and dosages, used to

treat EPS. The addition of a regularly scheduled oral anticholinergic such as

benztropine may allow the client to continue taking the antipsychotic drug with

no further dystonia. Recurrent dystonic reactions would necessitate a lower

dosage or a change in the antipsychoticdrug.

Drug-induced parkinsonism,

or pseudoparkinsonism, is often

referred to by the generic label of EPS. Symptoms resemble those of ParkinsonŌĆÖs

disease and include a stiff, stooped posture; mask-like facies; decreased arm

swing; a shuffling, festinating gait (with small steps); cogwheel rigid-ity

(ratchet-like movements of joints); drooling; tremor; bradycardia; and coarse

pill-rolling movements of the thumb and fingers while at rest. Parkinsonism is

treated by changing to an antipsychotic medication that has a lower incidence

of EPS or by adding an oral anticholinergic agent or amantadine, which is a

dopamine agonist that increases transmission of dopamine blocked by the

antipsychotic drug.

Akathisia is reported by the client as

an intense need to move about. The

client appears restless or anxious and agitated, often with a rigid posture or

gait and a lack of spontaneous gestures. This feeling of internal restlessness

and the inability to sit still or rest often leads clients to discontinue their

antipsychotic medication. Akathisia can be treated by a change in antipsychotic

medication or by the addition of an oral agent such as a beta-blocker,

anti-cholinergic, or benzodiazepine.

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is a potentially fatal idiosyncratic reac-tion to an antipsychotic

(or neuroleptic) drug. Although the Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, Text Revision (American Psychiatric Associa-tion,

2000) notes that the death rate from this syndrome has been reported at 10% to

20%, those figures may have resulted from biased reporting; the reported rates

are now decreasing. The major symptoms of NMS are rigidity; high fever;

autonomic instability such as unstable blood pres-sure, diaphoresis, and

pallor; delirium; and elevated levels of enzymes, particularly creatine

phosphokinase. Clients with NMS usually are confused and often mute; they may

fluctuate from agitation to stupor. All antipsychotics seem to have the

potential to cause NMS, but high dosages ofhigh-potency drugs increase the

risk. NMS most often occurs in the first 2 weeks of therapy or after an

increase in dosage, but it can occur at any time.

Dehydration, poor nutrition, and concurrent medical illness all

increase the risk for NMS. Treatment includes immediate discontinuance of all

antipsychotic medica-tions and the institution of supportive medical care to

treat dehydration and hyperthermia until the clientŌĆÖs physical condition

stabilizes. After NMS, the decision to treat the client with other

antipsychotic drugs requires full discussion between the client and the

physician to weigh the relative risks against the potential benefits of

therapy.

Tardive Dyskinesia. Tardive dyskinesia (TD), a syndro me of permanent involuntary

movements, is most commonly caused by the long-term use of conventional

antipsychotic drugs. About 20% to 30% of patients on long-term treatment

develop symptoms of TD (Sadock & Sadock, 2008). The pathophysiology is

still unclear, and no effective treatment has been approved for general use.

However, Woods, Saksa, Baker, Cohen, and Tek (2008) report success in treating

TD with levetiracetam in clinical trials. The symptoms of TD include

involuntary movements of the tongue, facial and neck muscles, upper and lower

extremities, andtruncal musculature. Tongue thrusting and protruding, lip

smacking, blinking, grimacing, and other excessive unnec-essary facial

movements are characteristic. After it has devel-oped, TD is irreversible,

although decreasing or discontinuing antipsychotic medications can arrest its

progression. Unfor-tunately, antipsychotic medications can mask the beginning

symptoms of TD; that is, increased dosages of the antipsy-chotic medication

cause the initial symptoms to disappear temporarily. As the symptoms of TD

worsen, however, they ŌĆ£break throughŌĆØ the effect of the antipsychotic drug.![]()

![]()

Preventing TD is one goal when administering antipsy-chotics. This

can be done by keeping maintenance dosages as low as possible, changing

medications, and monitoring the client periodically for initial signs of TD

using a stan-dardized assessment tool such as the Abnormal Involun-tary

Movement Scale . Clients who have already developed signs of TD but still need

to take an antipsychotic medication often are given one of the atypi-cal

antipsychotic drugs that have not yet been found to cause or, therefore, worsen

TD.

Anticholinergic side effects

Often occur with the use of antipsychotics and include orthostatic

hypotension, dry mouth, constipation, urinary hesitance or retention, blurred

near vision, dry eyes, pho-tophobia, nasal congestion, and decreased memory.

These side effects usually decrease within 3 to 4 weeks but do not entirely remit.

The client taking anticholinergic agents for EPS may have increased problems

with anticholinergic side effects. Using calorie-free beverages or hard candy

may alleviate dry mouth; stool softeners, adequate fluid intake, and the

inclusion of grains and fruit in the diet may prevent constipation.

Other Side Effects. Antipsychotic drugs also

increase blood prolactin levels. Elevated prolactin may

cause breast enlargement and tenderness in men and women; dimin-ished libido,

erectile and orgasmic dysfunction, and men-strual irregularities; and increased

risk for breast cancer, and may contribute to weight gain.

Weight gain can accompany most antipsychotic medi-cations, but it

is most likely with the atypical antipsy-chotic drugs, with ziprasidone

(Geodon) being the exception. Weight increases are most significant with

clozapine (Clozaril) and olanzapine (Zyprexa). Since 2004, the FDA has made it

mandatory for drug manufac-turers that atypical antipsychotics carry a warning

of the increased risk for hyperglycemia and diabetes. Though the exact

mechanism of this weight gain is unknown, it is associated with increased

appetite, binge eating, carbo-hydrate craving, food preference changes, and

decreased satiety in some clients. In addition, clients with a genetic

predisposition for weight gain are at greater risk (MullerKennedy, 2006).

Prolactin elevation may stimulate feeding centers, histamine antagonism

stimulates appe-tite, and there may be an as yet undetermined interplay of

multiple neurotransmitter and receptor interactions with resultant changes in

appetite, energy intake, and feeding behavior. Obesity is common in clients

with schizophre-nia, further increasing the risk for type 2 diabetes melli-tus

and cardiovascular disease (Newcomer & Haupt, 2006). In addition, clients

with schizophrenia are less likely to exercise or eat low-fat nutritionally

balanced diets; this pattern decreases the likelihood that they can minimize

potential weight gain or lose excess weight. It is recommended that clients

taking antipsychotics be involved in an educational program to control weight

and decrease body mass index.

Most antipsychotic drugs cause relatively minor cardio-vascular

adverse effects such as postural hypotension, palpi-tations, and tachycardia.

Certain antipsychotic drugs, such as thioridazine (Mellaril), droperidol

(Inapsine), and mesoridazine (Serentil), also can cause a lengthening of the QT

interval. A QT interval longer than 500 ms is considered dangerous and is

associated with life-threatening dysrhyth-mias and sudden death. Though rare,

the lengthened QT interval can cause torsade de pointes, a rapid heart rhythm

of 150 to 250 beats per minute, resulting in a ŌĆ£twistedŌĆØ appear-ance on the

electrocardiogram; hence the name torsade de pointes (Glassman, 2005).

Thioridazine and mesoridazine are used to treat psychosis; droperidol is most

often used as an adjunct to anesthesia or to produce sedation. Sertindole

(Serlect) was never approved in the United States to treat psychosis, but was

used in Europe and was subsequently withdrawn from the market because of the

number of cardiac dysrhythmias and deaths that it caused.

Clozapine produces fewer traditional side effects than do most

antipsychotic drugs, but it has the potentially fatal side effect of

agranulocytosis. This develops suddenly and is characterized by fever, malaise,

ulcerative sore throat, and leukopenia. This side effect may not be manifested

immediately and can occur up to 24 weeks after the initia-tion of therapy.

Initially, clients needed to have a weekly white blood cell count (WBC) above

3,500 per mm3 to obtain the next weekŌĆÖs supply of clozapine. Currently,

all clients must have weekly WBCs drawn for the first 6 months. If the WBC is

3,500 per mm3 and the absolute neutrophil count (ANC) is 2,000 per

mm3, the client may have these labs monitored every 2 weeks for 6

months, and then every 4 weeks. This decreased monitoring is dependent on

continuous therapy with clozapine. Any interruption in therapy requires a

return to more frequent monitoring for a specified period of time. After

clozapine has been discontinued, weekly monitoring of the WBC and ANC is required

for 4 weeks.

Related Topics