Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Personality Disorders

Schizoid Personality Disorder

Schizoid

Personality Disorder

Definition

The

schizoid personality disorder (SZPD) is a pervasive pattern of social

detachment and restricted emotional expression. Introver-sion (versus

extraversion) is one of the fundamental dimensions of general personality

functioning. Facets of introversion include low warmth (e.g., cold, detached,

impersonal), low gregarious-ness (socially isolated, withdrawn) and low

positive emotions (reserved, constricted or flat affect, anhedonic), which

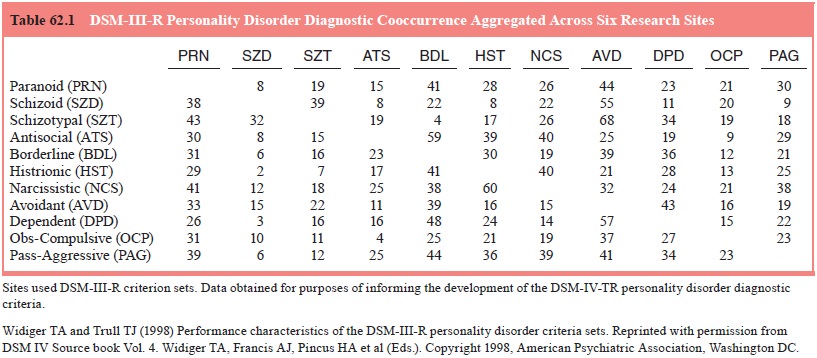

define well the central symptoms of SZPD (see Table 62.1). The presence of SZPD

is indicated by four or more of the seven diagnostic criteria presented in the

DSM-IV criteria for SZPD.

Etiology and Pathology

A

fundamental distinction for schizophrenic symptomatology is between positive

and negative symptoms. Positive symptoms include hallucinations, delusions,

inappropriate affect and loose associations; negative symptoms include

flattened affect, alogia, anhedonia and avolition. SZPD has been conceptualized

as rep-resenting subthreshold negative symptoms, comparable to the subthreshold

positive symptoms (cognitive–perceptual aberra-tions) that predominate

schizotypal personality disorder (STPD). However, a genetic link of SZPD to

schizophrenia that cannot be accounted for by comorbid STPD symptomatology has

not been well established. Research has supported heritability for the

personality dimension of introversion–extraversion and for the association of

SZPD with introversion. The central pathology of SZPD does appear to be

anhedonic deficits, or an excessively low ability to experience positive

affect. Psychosocial models for the etiology of SZPD are lacking. It is

possible that a sus-tained history of isolation during infancy and childhood,

with an encouragement and modeling by parental figures of interpersonal withdrawal,

indifference and detachment could contribute to the development of schizoid

personality traits.

Differential Diagnosis

SZPD can

be confused with the schizotypal and avoidant person-ality disorders as both

involve social isolation and withdrawal. Schizotypal personality disorder,

however, also includes an intense social anxiety and cognitive–perceptual

aberrations. The major distinction with avoidant personality disorder is the

absence of an intense desire for intimate social relationships. Avoidant persons

will also exhibit substantial insecurity and inhibition, whereas the schizoid

person is largely indifferent toward the reactions or opin-ions of others.

The

presence of premorbid schizoid traits can have prog-nostic significance for the

course and treatment of schizophrenia but, more importantly, it might not be

meaningful to suggest that a person has a schizoid personality disorder that is

independent of or unrelated to a comorbid schizophrenia. The negative,

pro-dromal and residual symptoms of schizophrenia resemble closely the features

of SZPD. Once a person develops schizophrenia, a diagnosis of SZPD can become

rather pointless as all of the schiz-oid symptoms can then be understood as

(prodromal or residual) symptoms of schizophrenia.

Epidemiology and Comorbidity

Approximately

half of the general population will exhibit an introversion within the normal

range of functioning. However, only a small minority of the population would be

diagnosed with a schizoid personality disorder. Estimates of the prevalence of

SZPD within the general population have been less than 1% and SZPD is among the

least frequently diagnosed personality disor-ders within clinical settings.

Many of the persons who were diag-nosed with SZPD prior to DSM-III are probably

now diagnosed with either the avoidant or the schizotypal personality disorders

and prototypic (pure) cases of SZPD are likely to be quite rare within the

population.

Course

Persons

with SZPD are socially isolated and withdrawn as chil-dren. They may not have

been accepted well by their peers, and may have even borne the brunt of some

ostracism (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). As adults, they have few

friend-ships. The friendships that do occur are likely to be initiated by their

peers or colleagues. They have few sexual relationships and may never marry.

Relationships fail to the extent to which the other person desires or needs

emotional support, warmth and intimacy. Persons with SZPD may do well and even

excel within an occupation, as long as substantial social interaction is not

required. They prefer to work in isolation. They may eventu-ally find

employment and a relationship that is relatively com-fortable, but they could

also drift from one job to another and remain isolated throughout much of their

life. If they do eventu-ally become a parent, they have considerable difficulty

providing warmth and emotional support, and they may appear neglectful,

detached and disinterested.

Treatment

Prototypic

cases of SZPD rarely present for treatment, whether it is for their schizoid

traits or a concomitant Axis I disorder. They feel little need for treatment,

as their isolation is often egosyn-tonic. Their social isolation is of more

concern to their relatives, colleagues, or friends than to themselves. Their

disinterest in and withdrawal from intimate or intense interpersonal contact is

also a substantial barrier to treatment. They at times appear depressed but one

must be careful not to confuse their anhedonic detach-ment, withdrawal and flat

affect with symptoms of depression.

If

persons with SZPD are seen for treatment for a concomi-tant Axis I disorder

(e.g., a sexual arousal disorder or a substance dependence) it is advisable to

work within the confines and limi-tations of the schizoid personality traits.

Charismatic, engaging, emotional, or intimate therapists can be very

uncomfortable, for-eign and even threatening to persons with SZPD. A more

busi-ness-like approach can be more successful.

It is

also important not to presume that persons with SZPD are simply inhibited, shy,

or insecure. Such persons are more appropriately diagnosed with the avoidant

personality disorder. Persons with SZPD are perhaps best treated with a

supportive psychotherapy that emphasizes education and feedback concern-ing interpersonal

skills and communication. One may not be able to increase the desire for social

involvements but one can increase the ability to relate to, communicate with

and get along with others. Persons with SZPD may not want to develop intimate

relationships but they will often want to interact and relate more effectively

and comfortably with others. The use of role playing and videotaped

interactions can at times be useful in this respect. Persons with SZPD can have

tremendous difficulty understand-ing how they are perceived by others or how

their behavior is unresponsive to and perceived as rejecting by others.

Group

therapy is often useful as a setting in which the patient can gradually develop

self-disclosure, experience the interest of oth-ers, and practice social

interactions with immediate and supportivefeedback. However, persons with SZPD

are prone to being rejected by a group due to their detachment, flat affect and

indifference to the feelings of others. If the group is patient and accepting,

they can benefit from the experience.

There

have been many studies on the pharmacologic treat-ment of the schizotypal PD

but no comparable studies on SZPD. The schizotypal and schizoid PDs share many

features, but the responsivity of the schizotypal PD to pharmacotherapy will

usu-ally reflect schizotypal social anxiety and cognitive–perceptual

aberrations that are not seen in prototypic, pure cases of SZPD.

Related Topics