Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Personality Disorders

Personality Disorder

Personality

Disorder

Definition

A

personality disorder is defined in DSM-IV-TR as “an enduring pattern of inner

experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectations of the

individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence

or early adulthood, is stable over time, and leads to distress or impairment”.

The DSM-IV-TR general diagnostic criteria for a personality disorder are

provided below.

Personality disorder is the only class of mental disorders in DSM-IV-TR for which an explicit definition and criterion set are provided. A general definition and criterion set can be useful to psychiatrists because the most common personality disorder di-agnosis in clinical practice is often the diagnosis “not otherwise specified” (NOS) (Clark et al., 1995). Psychiatrists provide the NOS diagnosis when they determine that a personality disorderis present but the symptomatology fails to meet the criterion set for one of the 10 specific personality disorders. A general defini-tion of what is meant by a personality disorder is therefore helpful when determining whether the NOS diagnosis should in fact be provided. Points worth emphasizing with respect to the general criterion set are presented in the following discussion of the as-sessment, differential diagnosis, epidemiology and course of per-sonality disorders

Etiology and Pathophysiology

A primary

purpose of a diagnosis is to lead to scientific knowledge concerning the

etiology for a patient’s condition and the identi-fication of a specific

pathology for which a particular treatment (e.g., medication) would ameliorate

the condition. However, many of the mental disorders in DSM-IV-TR, including

the personality disorders, may not in fact have single etiologies or even

specific pathologies. The DSM-IV-TR personality disorders might be, for the

most part, constellations of maladaptive personality traits that are the result

of multiple genetic dispositions interacting with a variety of detrimental

environmental experiences. The DSM-IV-TR personality disorder diagnoses do

provide the clinician with a substantial amount of important information

concerning the etiology and pathology for a patient’s particular personal-ity

syndrome, but there are likely to be alternative pathways to the development of

maladaptive personality traits and alterna-tive neurophysiological,

cognitive–behavioral, interpersonal and psychodynamic models for their

pathology (Livesley, 2001).

Assessment and Differential Diagnosis

Since

1980, the multiaxial system appears to have been successful in encouraging

psychiatrists no longer to make arbitrary distinc-tions between personality

disorders and other mental disorders. Ironically, however, the placement of the

personality disorders on a separate axis may have also contributed to the

development of false assumptions and misleading expectations concerning the

distinctions between personality disorders and other mental dis-orders with

respect to etiology, pathology, or treatment. It has been difficult to provide

a brief list of specific diagnostic criteria for the broad and complex behavior

patterns that constitute a per-sonality disorder. The only personality disorder

to be diagnosed reliably in general clinical practice has been antisocial and

the validity of this diagnosis has been questioned precisely because of its

emphasis on overt and behaviorally specific acts of crimi-nality,

irresponsibility and delinquency.

There are

assessment instruments, however, that will help psychiatrists obtain more

reliable and valid personality disor-der diagnoses. Semi-structured interviews

will obtain reliable diagnoses of personality disorders and are therefore the

preferred method for the assessment of personality disorders in clinical settings.

Semi-structured interviews provide a researched set of required and recommended

interview queries and observations to assess each of the personality disorder

diagnostic criteria. Psy-chiatrists can find the administration of a

semi-structured inter-view to be constraining but a major strength of

semi-structured interviews is their assurance through an explicit structure

that each relevant diagnostic criterion has in fact been systematically

assessed. Idiosyncratic and subjective interviewing techniques are much more

likely to result in gender- and culturally-biased assessments relative to

unstructured clinical interviews. The manuals that accompany a semi-structured

interview also pro-vide useful information for understanding the rationale of

each diagnostic criterion, for interpreting vague or inconsistent

symp-tomatology, and for resolving diagnostic ambiguities. There are currently

five semi-structured interviews for the assessment of the DSM-IV-TR (American

Psychiatric Association, 2000) per-sonality disorder diagnostic criteria: 1)

Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders (Zanarini et al., 1995); 2) International Personality Disorder Examination

(Loranger, 1999); 3) Personal-ity Disorder Interview-IV (Widiger et al., 1995); 4) Structured Clinical

Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis II PersonalityDisorders (First et al., 1997); and 5) Structured

Interview for DSM-IV-TR Personality Disorders (Pfohl et al., 1997). The par-ticular advantages and disadvantages of each

particular interview have been discussed extensively (Widiger and Coker, 2002).

The

administration of an entire personality disorder semi-structured interview can

take 2 hours, an amount of time that is impractical for routine clinical

practice. However, this time can be reduced substantially by first

administering a self-report questionnaire that screens for the presence of the

DSM-IV-TR personality disorders (Widiger and Coker, 2002). A psychiatrist can

then confine the interview to the few personality disorders that the

self-report inventory suggested would be present. Self-report inventories are

useful in ensuring that all of the personality disorders were systematically

considered and in alerting the clini-cian to the presence of maladaptive

personality traits that might otherwise have been missed. There are a number of

alternative self-report inventories that can be used and the advantages and

disadvantages of each of them have been discussed extensively (Widiger and

Coker, 2002).

Gender

and cultural biases are one potential source of inaccurate personality disorder

diagnosis that are worth noting in particular. One of the general diagnostic

criteria for personality disorder is that the personality trait must deviate

markedly from the expectations of a person’s culture (see DSM-IV-TR general

diagnostic criteria for personality disorders). The purpose of this cultural

deviation requirement is to compel clinicians to consider the cultural

background of the patient. A behavior pattern that appears to be aberrant from

the perspective of one’s own culture (e.g., submissiveness or emotionality)

could be quite normative and adaptive within another culture. The cultural

expectations or norms of the psychiatrist might not be relevant or applicable

to a patient from a different cultural background. However, one should not

infer from this requirement that a personality disorder is primarily or simply

a deviation from a cultural norm. Devia-tion from the expectations of one’s

culture is not necessarily mal-adaptive, nor is conformity to one’s culture

necessarily healthy. Many of the personality disorders may even represent (in

part) extreme or excessive variants of behavior patterns that are val-ued or

encouraged within a particular culture. For example, it is usually adaptive to

be confident but not to be arrogant, to be agreeable but not to be submissive,

or to be conscientious but not to be perfectionistic.

Epidemiology and Comorbidity

Virtually

all patients must have had a characteristic manner of thinking, feeling,

behaving and relating to others prior to the onset of an Axis I disorder that

could have an important impact on the course and treatment of the respective

mental disorder and many of these persons would be diagnosed with a DSM-IV-TR

personality. Estimates of the prevalence of personality disor-der within

clinical settings is typically above 50%. As many as 60% of inpatients within

some clinical settings would be diag-nosed with borderline personality disorder

and as many as 50% of inmates within a correctional setting could be diagnosed

with antisocial personality disorder. Although the comorbid presence of a

personality disorder is likely to have an important impact on the course and

treatment of an Axis I disorder the prevalence of personality disorder is

generally underestimated in clini-cal practice due in part to the failure to

provide systematic or comprehensive assessments of personality disorder

symptom-atology and perhaps as well to the lack of funding for the treat-ment of

personality disorders.

Approximately

10 to 15% of the general population would be diagnosed with one of the 10

DSM-IV-TR personality disor-ders, excluding PDNOS. However the studies of

community pop-ulations have important limitations that qualify their results.

For example, many of the studies sampled persons who would prob-ably have less

personality disorder pathology than a randomly selected sample (e.g., some

studies have sampled persons without any history of Axis I psychopathology) and

the studies have used either the DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association,

1980) or DSM-III-R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987) criterion sets

rather than DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Nevertheless,

the prevalence estimates are generally close to those provided in DSM-IV-TR.

There is

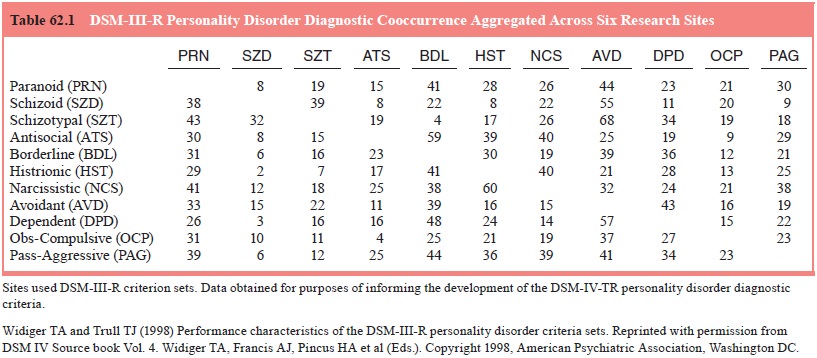

also considerable personality disorder diagnostic cooccurrence (Table 62.1).

Patients who meet the DSM-IV diag-nostic criteria for one personality disorder

are likely to meet the diagnostic criteria for another DSM-IV instructs

psychiatrists that all diagnoses should be recorded because it can be

impor-tant to consider (for example) the presence of antisocial traits in

someone with a borderline personality disorder or the pres-ence of paranoid

traits in someone with a dependent personality disorder. However, the extent of

diagnostic cooccurrence is at times so extensive that most researchers prefer a

more dimen-sional description of personality. Diagnostic categories provide

clear, vivid descriptions of discrete personality types but the per-sonality

structure of actual patients might be more accurately described by a

constellation of maladaptive personality traits.

Alternative

dimensional models of personality disorder are being developed. One such model,

based on a theory of tem-perament and character, consists of seven dimensions.

Cloninger (2000) proposes that there are four temperaments (reward depen-dence,

harm avoidance, novelty seeking and persistence), each governed by a particular

neurotransmitter system, and three character dimensions (self-directedness,

cooperativeness and self-transcendence). The presence of a personality disorder

is said to be determined primarily by the four temperaments and

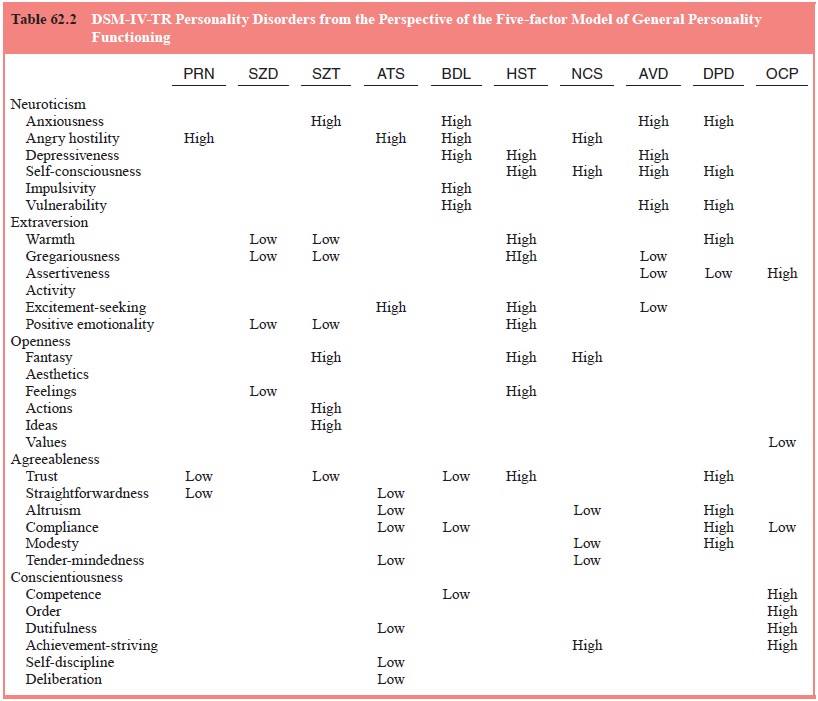

Table

62.2 provides a description of the DSM-IV-TR per-sonality disorders in terms of

this five-factor model. For example, the schizoid personality disorder may

represent an extreme vari-ant of introversion, avoidant may represent extreme

neuroticism and introversion, and antisocial personality disorder an extreme

variant of antagonism and undependability. Advantages of under-standing

personality disorders in terms of this dimensional model are the provision of

more specific descriptions of individual patients (including adaptive as well

as maladaptive personality functioning) and the avoidance of arbitrary

categorical distinc-tions. An additional factor is the ability to bring to bear

on an understanding of personality disorders the extensive amount of research

on the heritability, temperament, development and course of general personality

functioning.

Course

Personality

disorders must be evident since adolescence or young adulthood and have been

relatively chronic and stable throughout adult life (see DSM-IV-TR criteria for

personality disorders). The World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classifi cation of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10, World Health Organization, 1992) does recognize the existence of

personality change second- ary to catastrophic experiences and to brain injury

or disease, but only the latter is included within DSM-IV-TR (American

Psychiatric Association, 2000). A 75-year-old man can be diag-nosed with a

DSM-IV-TR dependent personality disorder but the symptoms must have been

present throughout the duration of his adulthood (e.g., since the age of 18

years) unless the dependent behavior was a direct, explicit expression of a

neurochemical dis-ease or lesion.

The

requirement that a personality disorder be evident since late adolescence and

be relatively chronic thereafter has been a traditional means with which to

distinguish a personal-ity disorder from an Axis I disorder. Mood, anxiety,

psychotic, sexual and other mental disorders have traditionally been

con-ceptualized as conditions that arise at some point during a person’s life

and that are relatively limited or circumscribed in their expression and

duration. Personality disorders, in contrast, are conditions that are evident

as early as late adolescence (and in some instances prior to that time), are

evident in everyday functioning, and are stable throughout adulthood. However,

the consistency of this distinction across disorders in the clas-sification has

been decreasing with each edition of the DSM, as early-onset and chronic

variants of Axis I disorders are being added to the diagnostic manual (e.g.,

early-onset dysthy-mia and generalized social phobia). Some researchers have in

fact suggested abandoning the concept of personality disorders and replacing

them with early-onset and chronic variants of existing Axis I disorders. For

example, avoidant personality disorder could become generalized social phobia,

obsessive– compulsive personality disorder could become an early-onset variant

of obsessive–compulsive anxiety disorder, and bor-derline personality disorder

could become an early-onset and chronic mood dyscontrol.

Treatment

One of

the mistaken assumptions or expectations of Axis II is that personality

disorders are untreatable. In fact, maladaptive personality traits are often

the focus of clinical attention. Person-ality disorders are among the more

difficult of mental disorders to treat as they involve entrenched behavior

patterns, some of which will be integral to a patient’s self-image.

Nevertheless, there is compelling empirical support to indicate that meaningful

respon-sivity to psychosocial and pharmacologic treatment does occur. Treatment

of a personality disorder is unlikely to result in the development of a fully

healthy or ideal personality structure, but clinically and socially meaningful

change to personality struc-ture and functioning does occur. In fact, given the

considerable social, occupational, medical and other costs that are engendered

by such personality disorders as the antisocial and borderline, even marginal

reductions in symptomatology can represent quite significant and meaningful

public health care, social and clinical benefits.

DSM-IV-TR

includes 10 individual personality disorder diagnoses that are organized into

three clusters: 1) paranoid, schizoid and schizotypal (placed within an

odd–eccentric clus-ter); 2) antisocial, borderline, histrionic and narcissistic

(dra-matic–emotional–erratic cluster); and 3) avoidant, dependent and

obsessive–compulsive (anxious–fearful cluster) (American Psy-chiatric

Association, 2000). Each of these personality disorders, along with the two

that are included in the appendix to DSM-IV-TR for disorders needing further

study (i.e., passive–aggressive and depressive), will be discussed in turn.

Related Topics