Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Personality Disorders

Borderline Personality Disorder

Borderline

Personality Disorder

Definition

Borderline

personality disorder (BPD) is a pervasive pattern of impulsivity and

instability in interpersonal relationships and self-image (American Psychiatric

Association, 2000). A broad domain of general personality functioning is

neuroticism or emotional instability. characterized by facets of angry

hostility, anxiousness, depressiveness, impulsivity and vulnerability; BPD is

essentially the most extreme and highly maladaptive variant of emotional

instability. This disorder is indicated by the presence of five or more of the

nine diagnostic criteria presented in the DSM-IV-TR criteria for BPD.

Etiology and Pathology

There are studies to indicate that BPD may breed true but most research has suggested an association with mood and impulse dyscontrol disorders. There is also consistent empirical support for a childhood history of physical and/or sexual abuse, as well as parental conflict, loss and neglect. It appears that past traumatic events are important in many if not most cases of BPD, contrib-uting to the overlap and association with post traumatic stress and dissociative disorders but the nature and age at which these events have occurred will vary. BPD may involve the interaction of a genetic disposition towards dyscontrol of mood and impulses (i.e., emotionally unstable temperament), with a cumulative and evolving series of intensely pathogenic relationships.

There are

numerous theories regarding the pathogenic mechanisms of BPD, most concern

issues regarding abandon-ment, separation, and/or exploitative abuse, which is

one of the reasons that frantic efforts to avoid abandonment is the first item

in the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criterion set. Persons with BPD have quite intense,

disturbed, and/or abusive relationships with the significant persons of their

past, including their parents, contributing to the development of malevolent

perceptions and expectations of others. These expectations, along with an impair-ment

in the ability to regulate affect and impulses may contribute to the

perpetuation of intense, angry and unstable relationships. Neurochemical

dysregulation is evident in persons with BPD but it is unclear whether this

dysregulation is a result, cause, or cor-relate of prior interpersonal traumas.

Assessment and Differential Diagnosis

All of

the DSM-IV assessment instruments described earlier include the assessment of

BPD. However, an instrument that is focused on the assessment of BPD is the

Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines-Revised (DIB-R; Zanarini et al., 1989). The DIB-R provides a more

thorough assessment of components of BPD (e.g., impulsivity, affective

dysregulation and cognitive–perceptual aberrations) than is provided by more

general DSM-IV-TR per-sonality disorder semi-structured interviews, but

psychiatrists might find it impractical to devote up to 2 hours to assess one

particular personality disorder, especially when it is likely that other

maladaptive personality traits not covered by the DIB-R are also likely to be

present.

Most

persons with BPD develop mood disorders and it is at times difficult to

differentiate BPD from a mood disorder if the assessment is confined to the

current symptomatology. A diagnosis of BPD requires that the borderline

symptomatology be evident since adolescence, which should differentiate BPD

from a mood disorder in all cases other than a chronic mood disorder. If there

is a chronic mood disorder, then the additional features of transient,

stress-related paranoid ideation, dissociative experi-ences, impulsivity and

anger dyscontrol that are evident in BPD should be emphasized in the diagnosis

(Gunderson, 2001).

Epidemiology and Comorbidity

Approximately

1 to 2% of the general population would meet the DSM-IV criteria for BPD. BPD

is the most prevalent personality disorder within maximum clinical settings.

Approximately 15% of all inpatients (51% of inpatients with a personality

disorder) and 8% of all outpatients (27% of outpatients with a personality disorder)

have a borderline personality disorder. Approximately 75% of persons with BPD

will be female. Persons with BPD meet DSM-IV-TR criteria for at least one Axis

I disorder. The range of potential Axis I comorbid psychopathology includes

mood (major depressive disorder), anxiety (post traumatic stress dis-order),

eating (bulimia nervosa), substance (alcohol dependence), dissociative

(dissociative identity disorder), and psychotic (brief psychotic) disorders

(Gunderson, 2001). Persons with BPD also meet DSM-IV-TR criteria for at least

one other personality dis-order, particularly histrionic, dependent,

antisocial, schizotypal, or passive–aggressive. Researchers and clinicians have

at times responded to this extensive cooccurrence by imposing a diag-nostic hierarchy

whereby other disorders are not diagnosed in the presence of BPD because BPD is

generally the most severely dysfunctional disorder (Gunderson et al., 2000). A potential limitation of

this approach is that it resolves the complexity of personality by largely

ignoring it. This approach may fail to rec-ognize the presence of maladaptive

personality traits that could be important for understanding a patient’s

dysfunctions and for developing an optimal treatment plan.

Course

As

children, persons with BPD are likely to have been emotionally unstable,

impulsive and angry or hostile. Their chaotic impulsiv-ity and intense

affectivity may contribute to involvement within rebellious groups as a child

or adolescent, along with a variety of Axis I disorders, including eating,

substance use and mood dis-orders. BPD is often diagnosed in children and

adolescents but considerable caution should be used when doing so as some of

the symptoms of BPD (e.g., identity disturbance and unstable rela-tionships)

could be confused with a normal adolescent rebellion or identity crisis. As

adults, persons with BPD may require numerous hospitalizations due to their

affect and impulse dyscontrol, psy-chotic-like and dissociative symptomatology

and risk of suicide. Minor problems quickly become crises as the intensity of

affect and impulsivity result in disastrous decisions. They are at a high risk

for developing depressive, substance-related, bulimic and post traumatic stress

disorders. The potential for suicide increases with comorbid mood and

substance-related disorder. Approximately 3 to 10% commit suicide by the age of

30 years. Relationships tend to be very unstable and explosive and employment

history is poor. Affectivity and impulsivity, however, may begin to diminish as

the person reaches the age of 30 years, or earlier if the person becomes

involved with a supportive and patient sexual partner. Some, however, may

obtain stability by abandoning the effort to obtain a relationship, opting

instead for a lonelier but less volatile life. The mellowing of the

symptomatology, however, can be eas-ily disrupted by the occurrence of a severe

stressor (e.g., divorce by or death of a significant other) that results in a

brief psychotic, dissociative, or mood disorder episode.

Treatment

Persons

with BPD often develop intense, dependent, hostile, un-stable and manipulative

relationships with their therapists as they do with their peers. At one time

they might be very compliant, responsive and even idealizing, but later angry,

accusatory and devaluing. Their tendency to be manipulatively as well as

impul-sively self-destructive is often very stressful and difficult to treat

(Stone, 2000).

Persons

with BPD are often highly motivated for treatment. Psychotherapeutic approaches

tend to be both supportive and ex-ploratory. Therapists should provide a safe,

secure environment in which anger can be expressed and actively addressed

without destroying the therapeutic relationship. The historical roots of

current bitterness, anger and depression within past familial rela-tionships

should eventually be explored, but immediate, current issues and conflicts must

also be explicitly addressed. Suicidal behavior should be confronted and

contained, by hospitalization when necessary. Patients with BPD can be very

difficult to treat because the focus of the patient’s love and wrath will often

be shifted toward the therapist, and the treatment may itself become the

patient’s latest unstable, intense relationship. Immediate and ongoing

consultation with colleagues is often necessary, as it is not unusual for

therapists to be unaware of the extent to which they are developing or

expressing feelings of anger, attraction, annoyance, or intolerance toward

their borderline patient.

A

particular form of cognitive–behavioral therapy, dialecti-cal behavior therapy,

has been shown empirically to be effective in the treatment of BPD (Linehan,

2000). Part of the strategy entailskeeping patients focused initially on the

priorities of reducing sui-cidal threats and gestures, behaviors that can

disrupt or resist treat-ment, and behaviors that affect the immediate quality

of life (e.g., bulimia, substance abuse, or unemployment). Once these goals are

achieved, the focus can then shift to a mastery of new coping skills,

management of reactions to stress and other individualized goals. Individual

therapy is augmented by skills-training groups that may be highly structured

(e.g., comparable to a classroom format). Patients are taught skills for coping

with identity diffu-sion, tolerating distress, improving interpersonal

relationships, controlling emotions and resolving interpersonal crises.

Patients are given homework assignments to practice these skills that are

further addressed and reinforced within individual sessions. Neg-ative affect

is also addressed through a mindful meditation that contributes to an

acceptance and tolerance of past abusive experi-ences and current stress. The

dialectical component of the therapy is that “the dialectical therapist helps

the patient achieve synthesis of oppositions, rather than focusing on verifying

either side of an oppositional argument”. An illustrative list of dialectical

strategies is presented in Table 62.3.

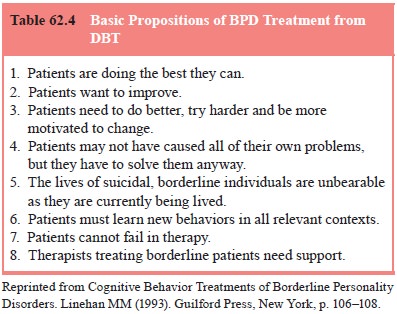

DBT,

however, also includes more general principles of treatment that are important

to emphasize in all forms of therapy for BPD (Linehan, 1993; Stone, 1993,

2000), some of which are presented in Table 62.4. For example, exasperated

therapists may unjustly experience and even accuse borderline patients of being

unmotivated or unwilling to work. It is important to appreciate that they do

want to improve and are doing the best that they can. One should not make the

therapy personal, but instead identify the sources of the inhibition or

interference to their motivation to change. One should take seriously their

complaints that their lives are indeed unbearable but not absolve them of their

responsibility to solve their own problems. They are unlikely to change simply

through a passive reception of insight, nurturance, support and

medication.

They will need to work actively on changing their lives. Therapists will often

be tempted to rescue their patients, particularly when they are within a

crisis. However, it is precisely at such times that there will be the best

opportunity to develop and learn new coping strategies. Failures can occur, and

it is a fail-ure of the therapy that should be conscientiously and effectively

addressed by the therapist. Finally, therapists need honestly to recognize

their own limitations. All therapists have their own flaws and limits and

patients with BPD invariably strain and overwhelm these limits. Therapists need

to be open and recep-tive to outside support, advice and criticism.

Pharmacologic

treatment of patients with BPD is varied, as it depends primarily on the

predominant Axis I symptomatology. Persons with BPD can display a wide variety

of Axis I symptoms, including anxiety, depression, hallucinations, delusions

and dis-sociations. It is important in their pharmacologic treatment not to be

unduly influenced by transient symptoms or by symptoms that are readily

addressed through exploratory or supportive tech-niques. On the other hand, it

is equally important to be flexible in the use of medications and not to be

unduly resistant to their use. Relying solely upon one’s own psychotherapeutic

skills can be unnecessary and even irresponsible.

Related Topics