Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Pain Management

Routes of Administration - Pain Management Strategies

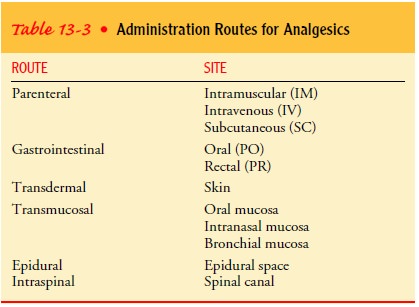

ROUTES

OF ADMINISTRATION

The route selected for

administering an analgesic agent (Table 13-3) depends on the patient’s

condition and the desired effect of the medication. Analgesic agents can be

administered by par-enteral, oral, rectal, transdermal, transmucosal,

intraspinal, or epidural routes. Each method of administration has advantages

and disadvantages. The route chosen should be based on the pa-tient’s needs.

Parenteral

Parenteral administration (intramuscular, intravenous, or subcu-taneous) of the analgesic medication produces effects more rapidly than oral administration, but these effects are of shorter duration.

Parenteral

administration may be indicated if the pa-tient is not permitted oral intake or

is vomiting. Medication ad-ministered by the intramuscular route enters the

bloodstream more slowly than medication given intravenously and is metabo-lized

slowly. The rate of absorption may be erratic; it depends on the site selected

and the amount of body fat.

The intravenous route is an alternative to intramuscular injec-tion for

many but not all analgesic medications. The intravenous route is the preferred

parenteral route in most acute care situations because it is much more

comfortable for the patient. In addition, peak serum levels and pain relief

occur more rapidly and reliably. Because it peaks rapidly (usually within

minutes) and is metabo-lized quickly, an appropriate intravenous dose will be

smaller and prescribed at shorter intervals than an intramuscular dose.

Intravenous opioids may

be administered by IV push or slow push (eg, over a 5- to 10-minute period) or

by continuous infu-sion with a pump. Continuous infusion provides a steady

level of analgesia and is indicated when pain occurs over a 24-hour pe-riod

(eg, after surgery for the first day or so, or in a patient with prolonged

cancer pain who cannot take medication by other routes). The dose of analgesic

agent is calculated carefully to re-lieve pain without producing respiratory

depression and other side effects.

The subcutaneous route for infusion of opioid analgesic agents is used

for patients with severe pain such as cancer pain; it is par-ticularly useful

for patients with limited intravenous access who cannot take oral medications,

and patients who are managing their pain at home. The dose of opioid that can

be infused through this route is limited because of the small volume that can

be administered at one time into the subcutaneous tissue. How-ever, this route

is often an effective and convenient way to man-age pain.

Oral Route

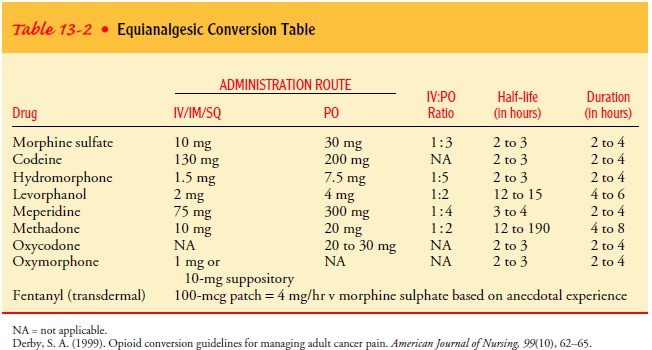

If the patient can take medication by mouth, oral administration is

preferred over parenteral administration because it is easy, non-invasive, and

not painful. Severe pain can be relieved with oral opioids if the doses are

high enough (see Table 13-2).

In terminally ill patients with prolonged pain, doses may gradually be

increased as the disease progresses and causes more pain or as the person

builds up a tolerance to the medication. If these higher doses are increased

gradually, they usually provide additional pain relief without producing

respiratory depressionor sedation. If the route of administration is

changed from a par-enteral route to the oral route at a dose that is not

equivalent in strength (equianalgesic), the smaller oral dose may result in a

withdrawal reaction and recurrence of pain.

Rectal Route

The rectal route of administration may be indicated in patients who

cannot take medications by any other route. The rectal route may also be

indicated for patients with bleeding problems, such as hemophilia. The onset of

action of opioids administered rec-tally is unclear but is delayed compared

with other routes of administration. Similarly, the duration of action is

prolonged.

Transdermal Route

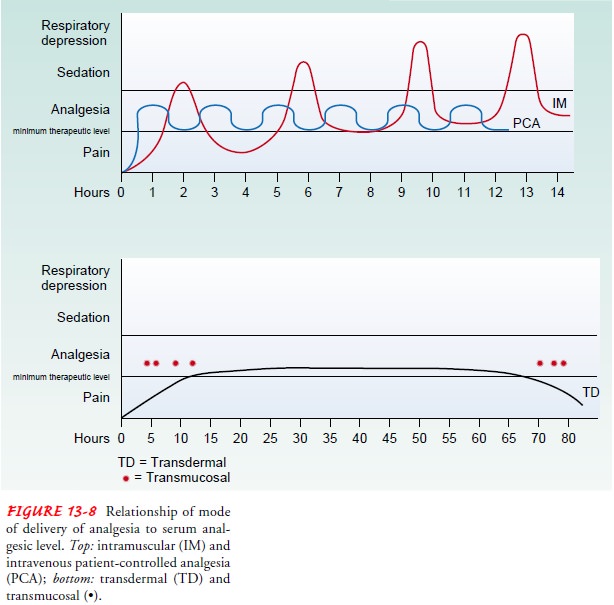

The transdermal route

has been used to achieve a consistent opi-oid serum level through absorption of

the medication via the skin. This route is most often used for cancer patients

who are at home or in hospice care and who have been receiving oral

sustained-release morphine. Fentanyl (Duragesic) is the only commercially available

transdermal medication. The preparation is a patch consisting of a reservoir

containing the medication and a membrane.

When the transdermal system is first applied to the skin, the fentanyl,

which is fat-soluble, binds to the skin and fat layers. Then it is slowly and

systemically absorbed. Therefore, there is a delay in effect while the dermal

layer is being saturated. A drug reservoir actually forms in the upper layer of

skin. This results in a slowly rising serum level and a slow tapering of the serum

level once the patch is removed (see Fig. 13-8). Because it takes 12 to 24

hours for the fentanyl levels to gradually increase from the first patch, the

last dose of sustained-release morphine should be given at the same time the

first patch is applied (Donner et al., 1996). Transdermal fentanyl is

associated with slightly less constipation than oral opioids. Absorption is

increased in the febrile patient. A heating pad should never be applied to the

area where the patch is applied. Transdermal fentanyl is much more expensive

than sustained-release morphine but less costly than methods that de-liver

parenteral opioids.

Once it is determined that switching from other routes of morphine

administration to the patch is appropriate, the correct dosage for the patch

must be calculated. If the patient uses an opioid other than morphine,

conversion to milligrams of oral morphine is the first step. After determining

how many mil-ligrams of morphine (or morphine equivalents) the patient has been

using over 24 hours, an initial dose of transdermal fentanyl can be calculated.

Pasaro (1997) suggests one method of calculating the initial dose of

fentanyl: the patient’s daily dose of morphine is divided by two. Thus, the

equivalent of 400 mg morphine used per day would be equivalent to 200 g

fentanyl per hour. Patients switched from morphine to fentanyl need to be

assessed not only for pain and potential side effects but also for dependence,

reflected by withdrawal symptoms, which may consist of shivering, a feel-ing of

coldness, sweating, headache, and paresthesia (Puntillo, Casella et al., 1997).

Patients may require short-acting opioids for breakthrough pain before the

systemic fentanyl level reaches a therapeutic level.

These conversions and the conversion-type table in the trans-dermal

fentanyl packet insert should be used only to establish the initial dose of

fentanyl when the patient switches from oral mor-phine to fentanyl (and not

vice versa). These tables and equationsare not meant to be used to determine

the dosages of oral mor-phine for a patient who has been receiving transdermal

fentanyl. Many patients will not achieve satisfactory analgesia from the

initial dose of transdermal fentanyl and will require an increase in their

fentanyl dose to treat breakthrough pain. If the table or equation is used

incorrectly to calculate a morphine dose, there is a risk of overdose. If the

patient requires a change from trans-dermal fentanyl back to oral or

intravenous morphine (as in the case of surgery), the patch should be removed

and intravenous morphine supplied on an assessed need basis.

Before applying a new

patch, the patient should be carefully checked for any older, forgotten

patches. These should be dis-carded. Patches should be replaced every 72 hours.

Transmucosal Route

The person with cancer pain who is being cared for at home may be

receiving continuous opioids using sustained-release morphine, hydromorphone,

oxycodone, transdermal fentanyl, or other med-ications. These patients often

experience short episodes of severe pain (eg, after coughing or moving), or

they may experience sud-den increases in their baseline pain resulting from a

change in their condition. These periods, called breakthrough pain, can be well

managed with an oral dose of a short-acting transmucosal opioid that has a

rapid onset of action. Currently the only transmucosal opioid available is

fentanyl, a lozenge on an applicator stick (often referred to as a lollipop by

patients).

Currently the only

approved and commercially available transmucosal opioid analgesic agents in a

nasal spray form are bu-torphanol (Stadol) and fentanyl. Butorphanol is a

complex med-ication that simultaneously acts to induce or promote (agonist) and inhibit or reverse (antagonist) opioid effects. It works

like an opioid agonist and an opioid antagonist at the same time. Butor-phanol

in any form cannot be combined with other opioids (eg, for cancer breakthrough

pain) because the antagonist com-ponent will block the action of the opioids

the patient is already receiving. The principal use of this agent is for brief,

moderate to severe pain, such as migraine headaches.

Intranasal fentanyl is useful in cancer-related breakthrough pain. Given

in this form, analgesia is achieved within 5 to 10 minutes and was rated as

achieving analgesia superior to oral morphine by 50% of patients in one study

(Zeppetella, 2000).

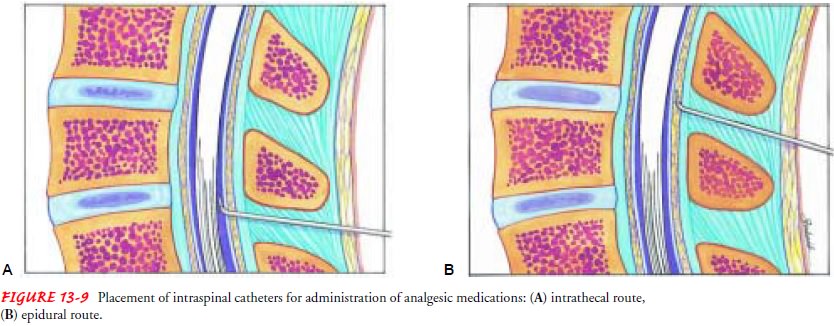

Intraspinal and Epidural Routes

Infusion of opioids or local anesthetic agents into the subarach-noid

space (intrathecal space or spinal canal) or epidural space has been used for

effective control of pain in postoperative patients and those with chronic pain

unrelieved by other methods. A catheter is inserted into the subarachnoid or

the epidural space at the thoracic or lumbar level for administration of opioid

or anes-thetic agents (Fig. 13-9). With intrathecal administration, the

medication infuses directly into the subarachnoid space and cerebrospinal

fluid, which surrounds the spinal cord. With epidural administration,

medication is deposited in the dura of the spinal canal and diffuses into the

subarachnoid space. It is be-lieved that pain relief from intraspinal

administration of opioids is based on the existence of opioid receptors in the

spinal cord.

Infusion of opioids and local anesthetic agents through an in-trathecal

or epidural catheter results in pain relief with fewer side effects, including

sedation, than with systemic analgesia. Adverse effects associated with

intraspinal administration include spinal headache resulting from loss of

spinal fluid when the dura is punc-tured. This is more likely to occur in

younger (less than 40 years of age) patients. The dura must be punctured with

the intrathecal route, and dural puncture may occur inadvertently with the

epidural route. When dural puncture inadvertently occurs, spinal fluid seeps

out of the spinal canal. The resultant headache is likely to be more severe

with an epidural needle because it is larger than a spinal needle, and

therefore more spinal fluid escapes.

Although respiratory depression generally peaks 6 to 12 hours after

epidural opioids are administered, it can occur earlier or up to 24 hours after

the first injection. Depending on the lipophilic-ity (affinity for body fat) of

the opioid injected, the time frame for respiratory depression can be short or

long. Morphine is hydro-philic, and the time for peak effect is longer compared

to fentanyl, which is a lipophilic opioid. All patients should be monitored

closely for at least the first 24 hours after the first injection, longer if

changes in respiratory status or level of consciousness occur. Opioid

antagonist agents such as naloxone must be available for intravenous use if

respiratory depression occurs.

The patient is also observed for urinary retention, pruritus, nausea, vomiting, and dizziness. Precautions must be taken to avoid infection at the catheter site and catheter displacement. Only medications without preservatives should be administered into the subarachnoid or epidural space because of the potential neurotoxic effects of preservatives.

During surgery, intrathecal opioids are used almost exclusively after a

spinal anesthetic agent is administered. For patients under-going large

abdominal surgical procedures, especially those at risk for postoperative complications,

a combination of a general in-haled anesthetic agent for the surgery and a

local epidural anes-thetic agent and epidural opioids administered after

surgery results in excellent pain control with fewer postoperative

complications.

Patients who have persistent, severe pain that fails to respond to other

treatments, or those who obtain pain relief only with the risk of serious side

effects, may benefit from medication administered by a long-term intrathecal or

epidural catheter. After the physician tunnels the catheter through the

subcutaneous tissue and places the inlet (or port) under the skin, the

medication is injected through the skin into the inlet and catheter, which

delivers the medication di-rectly into the epidural space. The medication may

need to be in-jected several times a day to maintain an adequate level of pain

relief.

In patients who require

more frequent doses or continuous in-fusions of opioid analgesic agents to

relieve pain, an implantable infusion device or pump may be used to administer

the medica-tion continuously. The medication is administered at a small,

con-stant dose at a preset rate into the epidural or subarachnoid space. The

reservoir of the infusion device stores the medication for slow release and

needs to be refilled every 1 or 2 months, depending on the patient’s needs.

This eliminates the need for repeated injec-tions through the skin.

NURSING MANAGEMENT OF SIDE EFFECTS

Headache resulting from spinal fluid loss may be delayed. There-fore,

the nurse needs to assess regularly for headache after either type of catheter

is placed. Should headache occur, the patient should remain flat in bed and

should be given large amounts of fluids (provided the medical condition

allows), and the physician should be notified. An epidural blood patch may be

carried out to reduce leakage of spinal fluid.

Cardiovascular effects

(hypotension and decreased heart rate) may result from relaxation of the

vasculature in the lower ex-tremities. Therefore, the nurse assesses frequently

for decreases in blood pressure, pulse rate, and urine output.

For patients experiencing urinary retention and pruritus, the physician

may prescribe small doses of naloxone. The nurse ad-ministers these doses in a

continuous intravenous infusion that is small enough to reverse the side

effects of the opioids without re-versing the analgesic effects.

Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) may also be used to relieve opioid-related pruritus.

PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE

The patient who receives epidural analgesic agents at home and the

family must be taught how to administer the prescribed med-ication using

sterile technique and how to assess for infection. The patient and family also

need to learn how to recognize side effects and what to do about them. Although

respiratory depres-sion is uncommon, urinary retention may be a problem, and

pa-tients and families must be prepared to deal with it if it occurs. Implanted

analgesic delivery systems can be safely and confi-dently used at home only if

health care personnel are available for consultation and, possibly,

intervention on short notice.

Related Topics