Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Pain Management

Pharmacologic Interventions - Pain Management Strategies

Pain Management Strategies

Reducing pain to a “tolerable” level was once considered the goal of

pain management. However, even patients who have described pain relief as

adequate often report disturbed sleep and marked distress because of pain. In

view of the harmful effects of pain and inadequate pain management, the goal of

tolerable pain has been replaced by the goal of relieving the pain. Pain

management strategies include both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic

ap-proaches. These approaches are selected on the basis of the pa-tient’s

requirements and goals. Appropriate analgesic medications are used as prescribed.

They are not considered a last resort to be used only when other pain relief

measures fail. Any intervention is most successful if initiated before pain

sensitization occurs, and the greatest success is usually achieved if several

interventions are applied simultaneously.

PHARMACOLOGIC

INTERVENTIONS

Managing a patient’s pain pharmacologically is accomplished in

collaboration with the physician or other primary care provider, the patient,

and often the family. The physician or nurse practi-tioner prescribes specific

medications for pain or may insert an intravenous line for administering

analgesic medications. Alter-natively, an anesthesiologist or nurse anesthetist

may insert an epidural catheter for their administration. However, it is the

nurse who maintains the analgesia, assesses its effectiveness, and reports if

the intervention is ineffective or produces side effects.

The pharmacologic management of pain requires close col-laboration and

effective communication among health care pro-viders. In the home setting, it

is often the family who manages the patient’s pain and assesses the

effectiveness of pharmacologic in-terventions, while it is the home care nurse

who evaluates the ad-equacy of pain relief strategies and the family’s ability

to manage the pain. The home care nurse reinforces teaching and ensures

communication among the patient, family care providers, physi-cian, pharmacist,

and other health care providers involved in the patient’s care.

Premedication Assessment

Before administering any

medication, the nurse asks the patient about allergies to medications and the

nature of any previous al-lergic responses. True allergic or anaphylactic

responses to opi-oids are rare, but it is not uncommon for a patient to report

an allergy to one of the opioids. On further examination, the nurse often

learns that the extent of the allergy was “itching” or “nau-sea and vomiting.”

These responses are not allergies; rather, they are side effects that, when

necessary, can be managed while the patient’s pain is relieved. The patient’s

description of responses or reactions should be documented and reported before

admin-istering the medication.

The nurse obtains the patient’s medication history (eg, cur-rent, usual,

or recent use of prescription or over-the-counter med-ications or herbal

agents), along with a history of health problems. Certain medications or

conditions may affect the analgesic med-ication’s effectiveness or the

metabolism and excretion of anal-gesic agents. Before administering analgesic

agents, the nurse should assess the patient’s pain status, including the

intensity of current pain, changes in pain intensity after the previous dose of

medication, and side effects of the medication.

Approaches for Using Analgesic Agents

Medications are most effective

when the dose and interval be-tween doses are individualized to meet the

patient’s needs. The only safe and effective way to administer analgesic

medications is by asking the patient to rate the pain and by observing the

re-sponse to medications.

BALANCED ANESTHESIA

Pharmacologic

interventions are most effective when a multi-modal or balanced analgesia

approach is used. Balanced analge-sia refers

to use of more than one form of analgesia concurrentlyto obtain more pain

relief with fewer side effects. Three general categories of analgesic agents

are opioids, NSAIDs, and local anesthetics. These agents work by different

mechanisms. Using two or three types of agents simultaneously can maximize pain

re-lief while minimizing the potentially toxic effects of any one agent. When

one agent is used alone, it usually must be used in a higher dose to be

effective. In other words, although it might re-quire 15 mg morphine to relieve

a certain pain, it may take only 8 mg morphine plus 30 mg ketorolac (an NSAID)

to relieve the same pain.

PRO RE NATA (PRN)

In the past, the

standard method used by most nurses and physi-cians in administering analgesia

was to administer the analgesic pro re

nata (PRN), or “as needed.” The standard practice was forthe nurse to wait

for the patient to complain of pain and then ad-minister analgesia. As a

result, many patients remained in pain because they did not know they needed to

ask for medication or waited until the pain became intolerable.

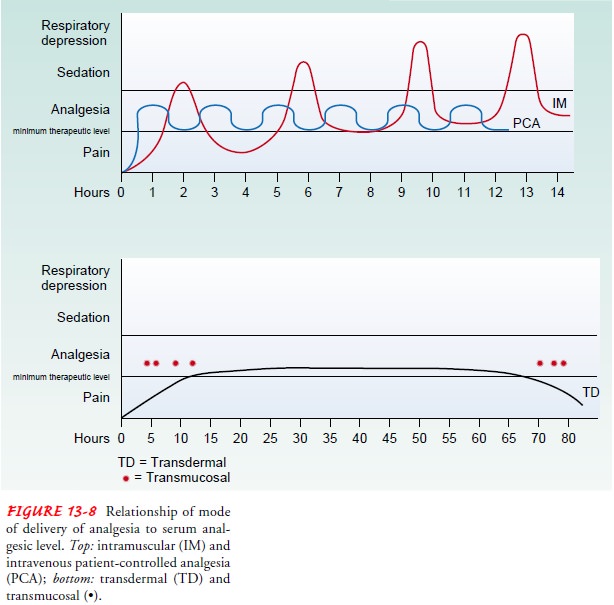

By its very nature, the

PRN approach to analgesia leaves the pa-tient sedated or in severe pain much of

the time. To receive pain relief from an opioid analgesic, the serum level of

that opioid must be maintained at a minimum therapeutic level (Fig. 13-8). By

the time the patient complains of pain, the serum opioid level is below the

therapeutic level. From the time the patient requests pain medication until the

nurse administers the medication, the patient’s serum level continues to fall.

The lower the serum opi-oid level, the more difficult it is to achieve the

therapeutic level with the next dose. The only way to ensure significant

periods of analgesia, using this method, is to give doses large enough to

pro-duce periods of sedation.

PREVENTIVE APPROACH

Currently, a preventive

approach to relieving pain by adminis-tering analgesic agents is considered the

most effective strategy because a therapeutic serum level of medication is

maintained. With the preventive approach, analgesic agents are administered at

set intervals so that the medication acts before the pain be-comes severe and

before the serum opioid level falls to a sub-therapeutic level.

Administering analgesic medication on a time basis, rather than on the basis of the patient’s report of pain, prevents the serum drug level from falling to subtherapeutic levels. An exam-ple of this would be giving the patient the prescribed morphine or the prescribed NSAID (ibuprofen) every 4 hours rather than waiting until the patient complains of pain.

If the patient’s pain is likely to occur around the clock or for a great portion of a 24-hour period, a regular around-the-clock schedule of administering analgesia may be indicated. Even if the analgesic is prescribed PRN, it can be administered on a preventive basis before the patient is in severe pain,

as long as the prescribed interval between doses is observed. The preventive

approach reduces the peaks and troughs in the serum level and provides more

pain relief for the patient with fewer adverse effects.

Smaller doses of medication are needed with the preventive approach

because the pain does not escalate to a level of severe in-tensity. Thus, a

preventive approach may result in the adminis-tration of less medication over a

24-hour period, thereby helping prevent tolerance to analgesic agents and

decreasing the severity of side effects (eg, sedation and constipation). Better

pain control can be achieved with a preventive approach, reducing the amount of

time the patient spends in pain.

In using the preventive approach, the nurse assesses the patient for

sedation before administering the next dose. The goal is to provide analgesia

before the pain becomes severe. It would not be safe to medicate a patient

(with an opioid) repeatedly if he or she was sedated or having no pain. It may

be necessary to decrease the dosage of the opioid analgesic so that the patient

receives pain relief with less sedation.

INDIVIDUALIZED DOSAGE

The dosage and the

interval between doses should be based on the patient’s requirements rather

than on an inflexible standard or routine. People metabolize and absorb

medications at differ-ent rates and experience different levels of pain.

Therefore, one dose of an opioid medication given at specified intervals may be

effective for one patient but ineffective for another.

Because of the fear of promoting addiction or causing respira-tory

depression, health care providers tend to prescribe and ad-minister inadequate

dosages of opioid agents to treat acute pain or chronic pain in the terminally

ill patient (Chart 13-5). How-ever, even prolonged administration of opioid

agents is associatedwith an extremely low incidence (less than 1%) of

addiction. Fur-thermore, small doses are not necessarily safe doses. For

example, some patients receiving a relatively small dose (25 to 50 mg) of

meperidine (Demerol) intramuscularly have experienced respira-tory depression,

whereas other patients have not exhibited any se-dation or respiratory

depression with very large doses of opioids.

Therefore, the effects of opioid analgesic medications must be

monitored, especially when the first dose is given or when the dose is changed

or given more frequently. The time, date, the pa-tient’s pain rating (scale of

0 to 10), the analgesic agent, other pain relief measures, side effects, and

patient activity are recorded. When the first dose of an analgesic is

administered, the nurse needs to record a pain rating score, blood pressure,

and respira-tory and pulse rates (all of which are considered “vital signs”).

If the pain has not decreased in 30 minutes (sooner if an intra-venous route is

used) and the patient is reasonably alert and has a satisfactory respiratory

status, blood pressure, and pulse rate, then some change in analgesia is

indicated. Although the dose of analgesic medication is safe for this patient,

it is ineffective in re-lieving the pain. Therefore, another dose of medication

may be indicated. In such instances, the nurse consults with the physi-cian to

determine what further action is warranted.

PATIENT-CONTROLLED ANALGESIA

Used to manage

postoperative pain as well as chronic pain, patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) allows patients to control the

ad-ministration of their own medication within predetermined safety limits.

This approach can be used with oral analgesic agents as well as with continuous

infusions of opioid analgesic agents by intra-venous, subcutaneous, or epidural

routes. PCA can be used in the hospital or home setting.

The PCA pump permits the patient to self-administer contin-uous infusions

of medication (basal rates) safely and to administer extra medication (bolus

doses) with episodes of increased pain or painful activities. A PCA pump is

electronically controlled by a timing device. Patients experiencing pain can

administer small amounts of medication directly into their intravenous,

sub-cutaneous, or epidural catheter by pressing a button. The pump then

delivers a preset amount of medication.

The PCA pump also can be

programmed to deliver a constant, background infusion of medication or basal

rate and still allow the patient to administer additional bolus doses as

needed. The timer can be programmed to prevent additional doses from being

administered until a specified time period has elapsed (lock-out time) and

until the first dose has had time to exert its maximal ef-fect. Even if the

patient pushes the button multiple times in rapid succession, no additional

doses are released. If another dose is re-quired at the end of the delay

period, the button must be pushed again to receive the dose. Patients who are

controlling their own opioid administration usually become sedated and stop

pushing the button before any significant respiratory depression occurs.

Nevertheless, assessing respiratory status remains a major role for the nurse.

A continuous infusion

plus bolus doses may be effective with cancer patients who require large doses

of analgesia, or for post-surgical patients. Although this allows more

uninterrupted sleep, the risk of sedation increases, especially when the

patient has min-imal or decreasing pain.

Patients who use PCA

achieve better pain relief (Walder, Schafer, Henzi et al., 2001) and often

require less pain medica-tion than those who are treated in the standard PRN

fashion. Because the patient can maintain a near-constant level of med-ication,

the periods of severe pain and sedation that occur with the traditional PRN

regimen are avoided.

To initiate PCA or any analgesia used at home or in the hos-pital, it is

important to avoid playing “catch-up.” Pain should be brought under control

before PCA starts, often by the use of an initial, larger bolus dose or loading

dose. Then, after control is achieved, the pump is programmed to deliver small

doses of medication at a time. If the patient with severe pain has a low serum level

of opioid analgesic because of an inadequate basal rate, it is difficult to

regain control with the small doses available by pump. Before the PCA pump is

used, repeated bolus doses of an intra-venous opioid may be administered as

prescribed over a short time until the pain is relieved. Then PCA is initiated.

If pain con-trol is not achieved with the maximal dose of medication

pre-scribed, further prescriptions are obtained. The goal is to achieve a

minimum therapeutic level of analgesia and to allow the patient to maintain

that level by using the PCA pump. The patient is in-structed not to wait until

the pain is severe before pushing the button to obtain a bolus dose. The

patient is also reminded not to become so distracted by an activity or visitor

that he or she for-gets to self-administer a prescribed dose of medication. One

po-tential drawback to distraction is that a patient who is using a PCA pump

may not self-administer any analgesia during the time of effective distraction.

When distraction ends suddenly (eg, the movie ends or the visitors leave), the

patient may be left without a therapeutic serum opioid level. When intermittent

distraction is used for pain relief, a continuous low-level background infusion

of opioid through the PCA pump may be prescribed so that when the distraction

ends, it will not be necessary to try to catch up.

If PCA is to be used in

the patient’s home, the patient and family are taught about the operation of

the pump and the side effects of the medication and strategies to manage them.

Local Anesthetic Agents

Local anesthetics work by blocking nerve conduction when ap-plied

directly to the nerve fibers. They can be applied directly to the site of

injury (eg, a topical anesthetic spray for sunburn) or di-rectly to nerve fibers

by injection or at the time of surgery. They can also be administered through

an epidural catheter.

TOPICAL APPLICATION

Local anesthetic agents have been successful in reducing the pain

associated with thoracic or upper abdominal surgery when in-jected by the

surgeon intercostally. Local anesthetic agents are rapidly absorbed into the

bloodstream, resulting in decreased availability at the surgical or injury site

and an increased anes-thetic level in the blood, increasing the risk of

toxicity. Therefore, a vasoconstrictive agent (eg, epinephrine or

phenylephrine) is added to the anesthetic agent to decrease its systemic

absorption and to maintain its concentration at the surgical or injury site.

A topical anesthetic

agent known as eutectic mixture or emul-sion of local anesthetics, or EMLA

cream, has been effective in preventing the pain associated with invasive

procedures such as lumbar puncture or the insertion of intravenous lines. To be

ef-fective, EMLA must be applied to the site 60 to 90 minutes be-fore the

procedure.

INTRASPINAL ADMINISTRATION

Intermittent or continuous administration of local anesthetic agents

through an epidural catheter has been used for years to produce anesthesia

during surgery. Although the administration of local anesthetic agents in the

spinal canal is still largely con-fined to acute pain, such as postoperative

pain and pain associ-ated with labor and delivery, the epidural administration

of local anesthetic agents for pain management is increasing.

A local anesthetic agent administered through an epidural catheter is

applied directly to the nerve root. The anesthetic agent can be administered

continuously in low doses, intermittently on a schedule, or on demand as the

patient requires it, and is often combined with the epidural administration of

opioids. Surgical patients treated with this combination experience fewer

compli-cations after surgery, ambulate sooner, and have shorter hospital stays

than patients receiving standard therapy (Correll, Viscusi, Grunwald et al., 2001).

Opioid Analgesic Agents

Opioids can be administered by various routes, including oral,

in-travenous, subcutaneous, intraspinal, intranasal, rectal, and trans-dermal

routes. The goal of administering opioids is to relieve pain and improve

quality of life; therefore, the route of administration, dose, and frequency of

administration are determined on an in-dividual basis. Factors that are

considered in determining the route, dose, and frequency of medication include

the character-istics of the pain (eg, its expected duration and severity), the

overall status of the patient, the patient’s response to analgesic medications,

and the patient’s report of pain. Although the oral route is usually preferred

for administering opioids, oral opioids must be given frequently enough and in

large enough doses to be effective. Opioid analgesic agents given orally may

provide a more consistent serum level than those given intramuscularly.

If the patient is

expected to require opioid analgesic agents at home, the patient’s and the

family’s ability to administer opioids as prescribed is considered in planning.

Steps are taken to ensure that the medication will be available to the patient.

Many phar-macies, especially those in smaller rural areas or inner cities, may

be reluctant to stock large amounts of opioids. Therefore, arrange-ments for

obtaining these prescription medications must be made ahead of time.

With the administration

of opioids by any route, side effects must be considered and anticipated.

Anticipating side effects and taking steps to minimize them increase the

likelihood that the pa-tient will receive adequate pain relief without

interrupting ther-apy to treat these effects.

RESPIRATORY DEPRESSION AND SEDATION

Respiratory depression is the most serious adverse effect of opi-oid

analgesic agents administered by intravenous, subcutaneous, or epidural routes.

However, it is relatively rare because doses ad-ministered through these routes

are small, and tolerance to respi-ratory depressant effects increases if the

dose is increased slowly. The risk of respiratory depression increases with age

and the con-comitant use of other opioids or other central nervous system

de-pressants. The risk of respiratory depression also increases when the

catheter is placed in the thoracic area and when the intra-abdominal or

intrathoracic pressure is increased.

The patient receiving opioids by any route must be assessed fre-quently

for changes in respiratory status. Specific notable changes are decreasing

respiratory rate or shallow respirations. Despite the risks associated with

their use, intravenous and epidural opioids are considered safe, with the risks

related to epidural administra-tion no greater than those related to

intravenous or other systemic routes of administration. Sedation, which may

occur with any method of administering opioids, is likely to occur when opioid

doses are increased. However, the patient often develops tolerance quickly, so

that in a short time the patient is no longer sedated by the dose that initially

caused sedation. Increasing the time between doses or reducing the dose

temporarily, as prescribed, usually prevents deep sedation from occurring. The

patient at risk for se-dation must be monitored closely for changes in

respiratory sta-tus. The patient is also at risk for other problems associated

with sedation and immobility. Therefore, the nurse must initiate strategies to

prevent problems such as skin breakdown.

NAUSEA AND VOMITING

Nausea and vomiting frequently occur with opioid use. Usually these

effects occur some hours after the initial injection. Patients, especially

postoperative patients, may not think to tell the nurse that they are

nauseated, particularly if the nausea is mild. How-ever, the patient receiving

an opioid should be assessed for nau-sea and vomiting, which may be triggered

by a position change and may be prevented by having the patient change

positions slowly. Adequate hydration and the administration of antiemetic

agents may decrease the incidence. Opioid-induced nausea and vomiting often

subside within a few days.

CONSTIPATION

Constipation, a common side effect of opioid use, may become so severe

that the patient is forced to choose between relief of pain and relief of

constipation. This situation can occur in patients after surgery and in

patients receiving large doses of opioids to treat cancer-related pain.

Preventing constipation must be a high priority in all patients receiving

opioids. Whenever a patient re-ceives opioids, a bowel regimen should begin at

the same time. Tolerance to this side effect does not occur; rather, it

persists even with long-term use of opioids.

Several strategies may help prevent and treat opioid-related

constipation. Mild laxatives and a high intake of fluid and fiber may be

effective in managing mild constipation. Unless con-traindicated, a mild

laxative and a stool softener should be ad-ministered on a regular schedule.

Continued severe constipation, however, often requires the use of a stimulating

cathartic agent, such as senna derivatives (Senokot) or bisacodyl (Dulcolax).

Oral laxatives and stool softeners may prevent constipation; rectal

sup-positories may be used if oral agents fail (Plaisance & Ellis, 2002).

INADEQUATE PAIN RELIEF

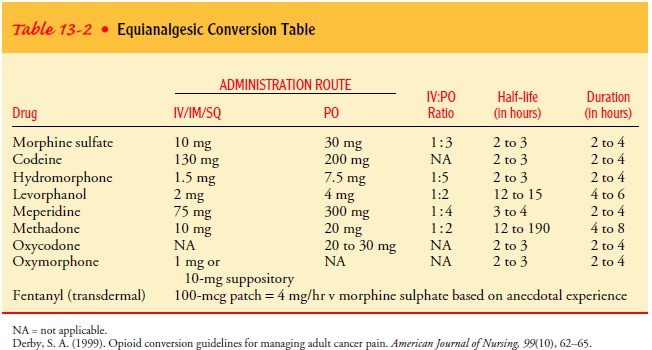

One factor commonly

associated with ineffective pain relief is an inadequate dose of opioid. This

is most likely to occur when the caregiver underestimates the patient’s pain or

the route of ad-ministration is changed without the differences in absorption

and action being considered. Consequently, the patient receives doses too small

to be effective and, possibly, too infrequently to relieve pain. For example,

if opioid delivery is changed from the intra-venous route to the oral route,

the oral dose must be approxi-mately three times greater than that given parenterally

to provide relief. Because of differences in absorption of orally administered

opioids among individuals, the patient must be assessed carefully to ensure

that the pain is relieved.

Table 13-2 lists opioids

and dosages that are equivalent to morphine. In general, no recalculation needs

to be done when switching from one brand of an agent to another brand of the

same medication, with the exception of extended-release oral morphine.

Currently, three brands of extended-release morphine (MS Contin, Oramorph,

Kadian) are commonly used by cancer patients. Although these agents come in the

same dosage form and contain the same drug, they are not considered

therapeuti-cally equivalent because they employ different release mecha-nisms.

Patients who need to switch brands should be monitored carefully both for

overdose and for inadequate pain relief.

OTHER EFFECTS OF OPIOIDS

During the health history, when asked about drug allergies, pa-tients

with previous hospital experience (especially for surgery) may report that they

are “allergic” to morphine. This report should be thoroughly investigated.

Commonly, this “allergy” will be described as itching only. Pruritus (itching)

is a frequent prob-lem associated with opioids administered through any route,

but it is not an allergic reaction. Itching can be relieved by adminis-tering

prescribed antihistamines. Epidurally administered opioids may also cause

urinary retention or pruritus. The patient should be monitored and may require

urinary catheterization. Small doses of naloxone may be prescribed to relieve

these problems in patients who are receiving epidural opioids for the relief of

acute postoperative pain.

A number of factors may

influence the safety and effectiveness of opioid administration. Opioid

analgesic agents are primarily metabolized by the liver and excreted by the

kidney. Therefore, metabolism and excretion of analgesic medications will be

im-paired in patients with liver or kidney disease, increasing the risk of cumulative

or toxic effects. In addition, normeperidine, a metabolite of meperidine, may

rapidly or unexpectedly accumu-late to toxic levels. This is more likely to

occur in patients with impaired kidney function and may result in seizures in

suscepti-ble patients.

Patients with untreated hypothyroidism are more susceptible to the

analgesic effects and side effects of opioids. In contrast, pa-tients with

hyperthyroidism may require larger doses for pain re-lief. Patients with a

decreased respiratory reserve from disease or aging may be more susceptible to

the depressant effects of opioids and must be carefully monitored for

respiratory depression.

Dehydrated patients are at increased risk for the hypotensive effects of

opioids. Patients who become hypotensive after the ad-ministration of an opioid

should be kept recumbent and rehydrated unless fluids are contraindicated.

Patients who are dehydrated are also more likely to experience nausea and

vomiting with opioid use. Rehydration usually relieves these symptoms.

Patients receiving

certain other medications, such as mono-amine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors,

phenothiazines, or tricyclic antidepressants, may have an exaggerated response

to the de-pressant effects of opioids. Patients taking these medications should

receive small doses of opioids and must be monitored closely. Continued pain in

these patients indicates that a thera-peutic level of the analgesic has not

been achieved. The patient must be monitored for sedation even if an analgesic

effect has not been obtained.

TOLERANCE AND ADDICTION

There is no maximum safe

dosage of opioids, nor is there any eas-ily identifiable therapeutic serum

level. Both the maximal safe dosage and therapeutic serum level are relative

and individual. Tolerance (the need

for increasing doses of opioids to achieve thesame therapeutic effect) will

develop in almost all patients taking opioids over an extended period. Patients

requiring opioids over a long term, especially cancer patients, will need

increasing doses to relieve pain. After the first few weeks of therapy, the

patient’s dosing requirements usually level off. Patients who become tol-erant

to the analgesic effects of large doses of morphine may ob-tain pain relief by

switching to a different opioid. Symptoms of physical dependence may occur when the opioids are discontin-ued; dependence

often occurs with opioid tolerance and does not indicate an addiction.

Addiction is a behavioral pattern of substance use character-ized by a compulsion

to take the drug primarily to experience its psychic effects. Fear that

patients will become addicted or de-pendent on opioids has contributed to

inadequate treatment of pain. This fear is commonly expressed by health care

providers as well as patients and results from lack of knowledge about the low

risk of addiction.

In an often-cited classic study (Porter & Jick, 1980) of more than

11,000 patients receiving opioids for a medical indication, only four patients

without a history of substance abuse could be identified as becoming addicted.

Addiction following therapeu-tic opioid administration is so negligible that it

should not be a consideration when caring for the patient in pain. Thus,

patients and health care providers should be dissuaded from withholding pain

medication because of concerns about addiction.

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

NSAIDs are thought to decrease pain by inhibiting cyclo-oxygenase (COX),

the rate-limiting enzyme involved in the production of prostaglandin from

traumatized or inflamed tissues. There are two types of COX: COX-1 and COX-2.

COX-1 is involved with mediating prostaglandin formation involved in the

maintenance of physiologic functions. Some of the physiologic functions

in-clude platelet aggregation through the provision of thromboxane precursors

and increased gastric mucosal blood flow. This pre-vents ischemia and promotes

mucosal integrity. Inhibition of COX-1 will result in gastric ulceration,

bleeding, and renal dam-age. The second type, COX-2, mediates prostaglandin

forma-tion that results in symptoms of pain, inflammation, and fever. Thus,

inhibition of COX-2 is desirable. Newer NSAIDs such as celecoxib (Celebrex),

rofecoxib (Vioxx), and valdecoxib (Bextra) are COX-2 inhibitors. Ibuprofen

(Advil, Motrin), another NSAID, blocks both COX-1 and COX-2 and is effec-tive

in relieving mild to moderate pain and has a low incidence of adverse effects.

Aspirin, the oldest NSAID, also blocks COX-1 as well as COX-2; however, because

it causes frequent and severe side effects, aspirin is infrequently used to

treat significant acute or chronic pain.

NSAIDs are very helpful in treating arthritic diseases and may be

especially powerful in treating cancer-related bone pain. They have been

effectively combined with opioids to treat postopera-tive and other severe

pain. The use of an NSAID with an opioid relieves pain more effectively than

the opioid alone. In such cases, the patient may obtain pain relief with less

opioid and fewer side effects. It has been shown that intraoperative

administration of NSAIDs results in improved postoperative pain control

follow-ing laparoscopic surgery and in some cases shorter hospital stays

(McLaughlin, 1994).

A regimen of a

fixed-dose, time-contingent NSAID (eg, every 4 hours) and a separately

administered fluctuating dose of opioid may be effective in managing moderate

to severe cancer pain. In more severe pain, the opioid dose will also be fixed,

with an addi-tional fluctuating dose as needed for breakthrough pain (a sud-den increase in pain despite the

administration of pain-relieving medications). These regimens result in better

pain relief with fewer opioid-related side effects.

Most patients tolerate NSAIDs well. However, those with im-paired kidney

function may require a smaller dose and must be monitored closely for side

effects. Patients taking NSAIDs bruise easily because NSAIDs have some

anticoagulant effect. More-over, they may displace other medications, such as

warfarin (Coumadin), from serum proteins and increase their effects. High doses

or prolonged use can irritate the stomach and in some cases result in

gastrointestinal bleeding as well. Thus, monitoring the patient for

gastrointestinal bleeding is indicated.

Gerontologic

Considerations Related to Analgesic Agents

Physiologic changes in older adults require that analgesic agents be

administered with caution. Drug interactions are more likely to occur in older

adults because of the higher incidence of chronic illness and the increased use

of prescription and over-the-counter medications. Although the elderly

population is an extremely het-erogeneous group, differences in response to

pain or medications by a patient in this 40-year span (60 to 100 years) are

more likely to be due to chronic illness or other individual factors than age.

Before administering opioid and nonopioid analgesic agents to elderly patients,

the nurse needs to obtain a careful medication history to identify potential

drug interactions.

Absorption and metabolism of medications are altered in elderly patients

because of decreased liver, renal, and gastrointestinal func-tion. In addition,

changes in body weight, protein stores, and dis-tribution of body fluid alter

the distribution of medications in the body. As a result, medications are not

metabolized as quickly and blood levels of the medication remain higher for a

longer period. Elderly patients are more sensitive to medications and at an

in-creased risk for drug toxicity (American Geriatrics Society, 1998).

Opioid and nonopioid analgesic medications can be given ef-fectively to

elderly patients but must be used cautiously because of the increased

susceptibility to depression of both the nervous and the respiratory systems.

Although there is no reason to avoid opioids simply because a person is

elderly, meperidine should be avoided because its active and neurotoxic

metabolite, normeperi-dine, is more likely to accumulate in the elderly. In

addition, be-cause of decreased binding of meperidine by plasma proteins, blood

concentrations of the medication twice those found in younger patients may

result.

In many cases, the initial dose of analgesic medication prescribed for

an elderly patient may be the same as that for a younger person, or slightly

smaller than the normal dose, but because of slowed me-tabolism and excretion

related to aging, the safe interval for subse-quent doses may be longer (or

prolonged). As always, the best guide to pain management and administration of

analgesic agents in all patients regardless of age is what the patient says.

The elderly pa-tient may obtain more pain relief for a longer time than a

younger patient. As a result, smaller, less frequent doses may be required. The

American Geriatrics Society (2002) has published clinical prac-tice guidelines

for managing chronic pain in elderly patients.

Tricyclic Antidepressant Agents and Anticonvulsant Medications

Pain of neurologic origin (eg, causalgia, tumor impingement on a nerve,

postherpetic neuralgia) is difficult to treat and in general is not responsive

to opioid therapy. When these pain syndromes are accompanied by dysesthesia (burning

or cutting pain), they may be responsive to a tricyclic antidepressant or an

antiseizure agent. When indicated, tricyclic antidepressant agents, such as

amitriptyline (Elavil) or imipramine (Tofranil), are prescribed in doses

considerably smaller than those generally used for depres-sion. The patient

needs to know that a therapeutic effect may not occur before 3 weeks.

Antiseizure medications such as phenytoin (Dilantin) or carbamazepine

(Tegretol) also are used in doses lower than those prescribed for seizure

disorders. Because a vari-ety of medications can be tried, the nurse should be

familiar with the possible side effects and should teach the patient and family

how to recognize these effects.

Related Topics