Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Pain Management

Neurologic and Neurosurgical Approaches to Pain Management

Neurologic and Neurosurgical Approaches to Pain

Management

In some situations, especially with long-term and severe in-tractable

pain, usual pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic methods of pain relief are

ineffective. In those situations, neuro-logic and neurosurgical approaches to

pain management may be considered. Intractable pain refers to pain that cannot

be relieved satisfactorily by the usual approaches, including medications. Such

pain usually is the result of malignancy (especially of the cervix, bladder,

prostate, and lower bowel), but it may occur in other conditions, such as

postherpetic neuralgia, trigeminal neu-ralgia, spinal cord arachnoiditis, and

uncontrollable ischemia and other forms of tissue destruction.

Neurologic and

neurosurgical methods available for pain relief include (1) stimulation

procedures (intermittent electrical stimulation of a tract or center to inhibit

the transmission of pain impulses), (2) administration of intraspinal opioids

(see pre-vious discussion), and (3) interruption of the tracts conducting the

pain impulse from the periphery to cerebral integration cen-ters. The latter

are destructive or ablative procedures, and their effects are permanent.

Ablative procedures are used when other methods of pain relief have failed.

STIMULATION PROCEDURES

Electrical stimulation, or neuromodulation, is a method of sup-pressing

pain by applying controlled low-voltage electrical pulses to the different

parts of the nervous system. Electrical stimulation is thought to relieve pain

by blocking painful stimuli (the gate control theory). This pain-modulating

technique is administered by many modes. TENS and dorsal spinal cord

stimulation are the most common types of electrical stimulation used. (See

previous discussion of TENS.) In addition, there are also brain-stimulating

techniques in which electrodes are implanted in the periventric-ular area of

the posterior third ventricle, allowing the patient to stimulate this area to

produce analgesia.

In spinal cord stimulation, a technique used for the relief of chronic,

intractable pain, ischemic pain, and pain from angina, a surgically implanted

device allows the patient to apply pulsed electrical stimulation to the dorsal

aspect of the spinal cord to block pain impulses (Linderoth & Meyerson,

2002). (The largest accumulation of afferent fibers is found in the dorsal

column of the spinal cord.) The dorsal column stimulation unit consists of a

radiofrequency stimulation transmitter, a transmitter antenna, a radiofrequency

receiver, and a stimulation electrode. The battery-powered transmitter and

antenna are worn externally; the re-ceiver and electrode are implanted. A

laminectomy is performed above the highest level of pain input, and the

electrode is placed in the epidural space over the posterior column of the

spinal cord. (The placement of the stimulating systems varies.) A subcutaneous

pocket is constructed over the clavicular area or some other site for placement

of the receiver. The two are connected by a sub-cutaneous tunnel. Careful

patient selection is necessary, and not all patients receive total pain relief.

Deep brain stimulation is performed for special pain prob-lems when the

patient does not respond to the usual techniques of pain control. With the

patient under local anesthesia, electrodes are introduced through a burr hole

in the skull and inserted into a selected site in the brain, depending on the

location or type of pain. After the effectiveness of stimulation is confirmed,

the im-planted electrode is connected to a radiofrequency device or

pulse-generator system operated by external telemetry. It is used in

neuropathic pain that may occur with damage or injury that oc-curred following

stroke, brain or spinal cord injuries, or phantom limb pain. Use of deep brain

stimulation has decreased and may be related to improved pain control and

intraspinal therapies (Rezai & Lozano, 2002).

Interruption of Pain Pathways

As described above, stimulation of a peripheral nerve, the spinal cord,

or the deep brain using minute amounts of electricity and a stimulating device

is used if all other pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatments fail to

provide adequate relief. These treatments are reversible. If they need to be

discontinued, the ner-vous system continues to function. Treatments that

interrupt the pain pathways, however, are permanent.

Pain-conducting fibers

can be interrupted at any point from their origin to the cerebral cortex. Some

part of the nervous system is destroyed, resulting in varying amounts of

neurologic deficit and incapacity. In time, pain usually returns as a result of

either regeneration of axonal fibers or the development of alter-native pain

pathways.

Destructive procedures used to interrupt the transmission of pain

include cordotomy and rhizotomy. These procedures are of-fered if the patient

is thought to be near the end of life and will have an improved quality of life

as an outcome (Linderoth & Meyerson, 2002). Often these procedures can

provide pain relief for the duration of a patient’s life. The use of other

methods to interrupt pain transmission is waning since the use of intraspinal

therapies and newer pain management treatments are available.

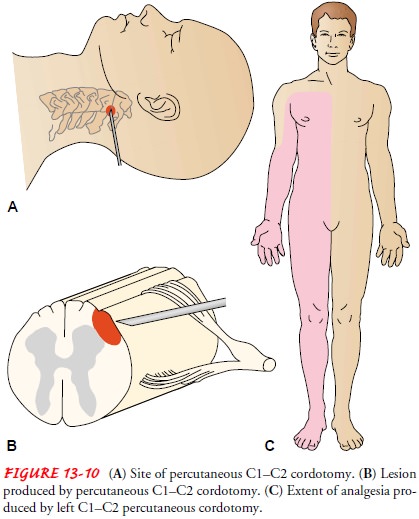

CORDOTOMY

A cordotomy is the

division of certain tracts of the spinal cord (Fig. 13-10). It may be performed

percutaneously, by the open method after laminectomy, or by other techniques.

Cordotomy is performed to interrupt the transmission of pain (Hodge &

Christensen, 2002). Care must be taken to destroy only the sen-sation of pain,

leaving motor functions intact.

RHIZOTOMY

Sensory nerve roots are

destroyed where they enter the spinal cord. A lesion is made in the dorsal root

to destroy neuronal dys-function and reduce nociceptive input. With the advent

of micro-surgical techniques, the complications are few, with mild sensory

deficits and mild weakness (Fig. 13-11).

Nursing Interventions

With each of these procedures, patients are provided with written and verbal instructions about their expected effect on pain and on possible untoward consequences.

The patient is monitored for specific effects of each method of pain intervention, both positive and

negative. The specific nursing care of patients who undergo neurologic and

neurosurgical procedures for the relief of chronic pain depends on the type of

procedure performed, its effectiveness in relieving the pain, and the changes

in neurologic function that accompany the procedure. After the procedure, the

patient’s pain level and neurologic function are assessed. Other nursing

inter-ventions that may be indicated include positioning, turning and skin

care, bowel and bladder management, and interventions to promote patient

safety. Pain management remains an important aspect of nursing care with each

of these procedures.

ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES

People suffering chronic, debilitating pain are often desperate. Often

they will try anything, recommended by anyone, at any price. Information about

an array of potential therapies can be found on the Internet and in the

self-help section of the book-store. Therapies specifically recommended for

pain from these sources include but are not limited to chelation, therapeutic

touch, music therapy, herbal therapy, reflexology, magnetic ther-apy,

electrotherapy, polarity therapy, acupressure, emu oil, pectin therapy,

aromatherapy, homeopathy, and macrobiotic dieting. Many of these “therapies”

(with the exception of macrobiotic di-eting) are probably not harmful. However,

they have yet to be proven effective by the standards used to evaluate the

effective-ness of medical and nursing interventions. The National Institutes of

Health has established an office to examine the effectiveness of alternative

therapies.

Despite the lack of

scientific evidence that these therapies are effective, a patient may find any

one of them helpful via theplacebo response. It is important when caring for a

patient who is using or considering using untested therapies (often referred to

as alternative therapies) not to diminish the patient’s hope and potential

placebo response. This must be weighed against the professional nurse’s

responsibility to protect the patient from costly and potentially harmful and

dangerous therapies that the patient is not in a position to evaluate

scientifically.

Problems arise when

patients do not find relief but are de-prived of conventional therapy because

the alternative therapy “should be helping,” or when patients abandon

conventional therapy for alternative therapy. In addition, few alternative

ther-apies are free. Desperate patients may risk financial ruin seeking

alternative therapies that do not work.

The nurse’s role is to

help the patient and family understand scientific research and how that differs

from anecdotal evidence. Without diminishing the placebo effects the patient

may receive, the nurse encourages the patient to assess the effectiveness of

the therapy continually using standard pain assessment techniques. In addition,

the nurse encourages the patient using alternative therapies to combine them

with conventional therapies and to discuss this use with the physician.

Related Topics