Chapter: Medical Physiology: Renal Regulation of Potassium, Calcium, Phosphate, and Magnesium; Integration of Renal Mechanisms for Control of Blood Volume and Extracellular Fluid Volume

Role of Angiotensin II In Controlling Renal Excretion

Role of Angiotensin II In Controlling Renal Excretion

One of the body’s most powerful controllers of sodium excretion is angiotensin II. Changes in sodium and fluid intake are associated with reciprocal changes in angiotensin II formation, and this in turn contributes greatly to the maintenance of body sodium and fluid balances. That is, when sodium intake is elevated above normal, renin secretion is decreased, causing decreased angiotensin II formation. Because angiotensin II has several important effects in increas-ing tubular reabsorption of sodium, a reduced level of angiotensin II decreases tubular reabsorption of sodium and water, thus increasing the kidneys’ excretion of sodium and water. The net result is to minimize the rise in extracellular fluid volume and arterial pressure that would other-wise occur when sodium intake increases.

Conversely, when sodium intake is reduced below normal, increased levels of angiotensin II cause sodium and water retention and oppose reductions in arterial blood pressure that would otherwise occur. Thus, changes in activity of the renin-angiotensin system act as a powerful amplifier of the pressure natriuresis mechanism for maintaining stable blood pressures and body fluid volumes.

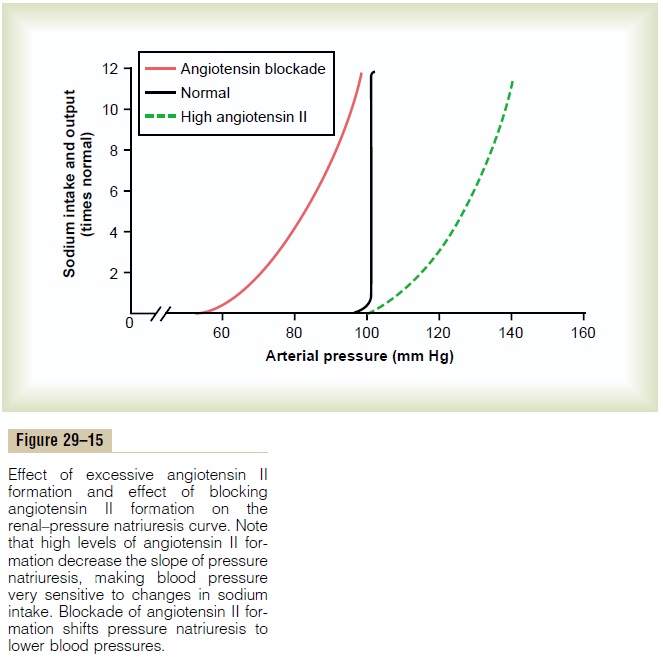

Importance of Angiotensin II in Increasing Effectiveness of Pressure Natriuresis. The importance of angiotensin IIin making the pressure natriuresis mechanism more effective is shown in Figure 29–15. Note that when the angiotensin control of natriuresis is fully functional, the pressure natriuresis curve is steep (normal curve), indicating that only minor changes in blood pressure are needed to increase sodium excretion when sodium intake is raised.

In contrast, when angiotensin levels cannot be decreased in response to increased sodium intake (high angiotensin II curve), as occurs in some hyper-tensive patients who have impaired ability to decrease renin secretion, the pressure natriuresis curve is not nearly as steep. Therefore, when sodium intake is raised, much greater increases in arterial pressure are needed to increase sodium excretion and maintain sodium balance. For example, in most people, a 10-fold increase in sodium intake causes an increase of only a few millimeters of mercury in arterial pressure, whereas in subjects who cannot suppress angiotensin

II formation appropriately in response to excess sodium, the same rise in sodium intake causes blood pressure to rise as much as 50 mm Hg. Thus, the inabil-ity to suppress angiotensin II formation when there is excess sodium reduces the slope of pressure natriure-sis and makes arterial pressure very salt sensitive.

The use of drugs to block the effects of angiotensin II has proved to be important clinically for improv-ing the kidneys’ ability to excrete salt and water. When angiotensin II formation is blocked with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (see Figure 29–15) or an angiotensin II receptor antagonist, the renal–pressure natriuresis curve is shifted to lower pressures; this indicates an enhanced ability of the kidneys to excrete sodium because normal levels of sodium excretion can now be maintained at reduced arterial pressures. This shift of pressure natriuresis provides the basis for the chronic blood pressure–lowering effects in hypertensive patients of the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor antagonists.

Excessive Angiotensin II Does Not Cause Large Increases in Extracellular Fluid Volume Because Increased Arterial Pressure Counterbalances Angiotensin-Mediated Sodium Retention.

Although angiotensin II is one of the most powerful sodium- and water-retaining hormones in the body, neither a decrease nor an increase in circulating angiotensin II has a large effect on extracellular fluid volume or blood volume. The reason for this is that with large increases in angiotensin II levels, as occurs with a renin-secreting tumor of the kidney, the high angiotensin II levels initially cause sodium and water retention by the kidneys and a small increase in extracellular fluid volume. This also initi-ates a rise in arterial pressure that quickly increases kidney output of sodium and water, thereby overcom-ing the sodium- and water-retaining effects of the angiotensin II and re-establishing a balance between intake and output of sodium at a higher blood pres-sure. Conversely, after blockade of angiotensin II for-mation, as occurs when an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor is administered, there is initial loss of sodium and water, but the fall in blood pressure offsets this effect, and sodium excretion is once again restored to normal.

Related Topics