Chapter: Essential Anesthesia From Science to Practice : Clinical management : Vascular access and fluid management

Risks - Fluid management

Risks

Blood

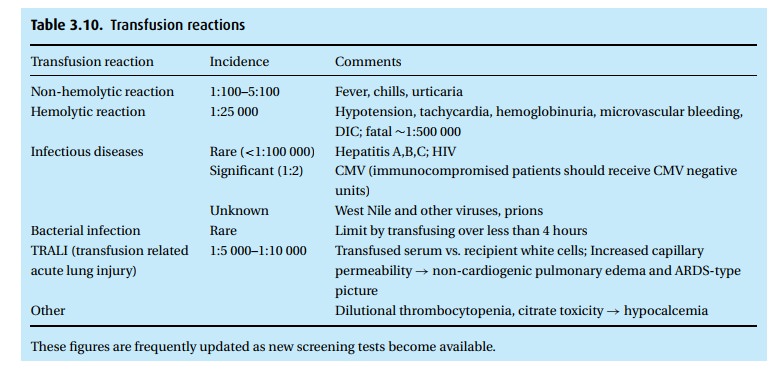

transfusions are inherently dangerous (Table 3.10).

In addition to the frequent non-hemolytic reactions, ABO incompatibility

threatens the poten-tial of a hemolytic reaction with hypotension, hematuria,

and fever. The diag-nosis can be made more readily if the patient is awake

since the symptoms of nausea, vomiting, flank or back pain and dizziness

frequently accompany a transfusion reaction.

Therapy includes stopping the infusion immediately (we return

both the remaining banked blood and a sample from the patient for testing),

treating mild symptoms with antihistamines and acetaminophen to reduce fever,

and perhaps adding corticosteroids to reduce the immune response. We worry most

about the potential for shock, kidney failure, and dissemi-nated intravascular

coagulation (DIC). In this last nasty syndrome, the antigen/ antibody reaction

can trigger factor XII (Hageman) which kicks the kinin system into action

leading to the generation of bradykinin and, through it, damage of endothelium

(oozing), hypotension, and thrombosis via the release of endo-genous tissue

thromboplastin. Human error plays a large part in transfusion reac-tions, which

account for more than half of transfusion-related deaths . . . transla-tion, double check all blood (patient and donor

blood types) before transfusing!

Unfortunately,

there are several types of transfusion reactions, and some can manifest even

several days after the transfusion.

As we

are largely water, maintenance of the patient’s fluid status represents one of

anesthesiology’s greatest challenges. Using vigilance, anticipation,

appropriate monitors, and vascular access, we manage fluids, blood, and blood

products to maintain stability and perfusion of vital organs.

Related Topics