Chapter: Essential Anesthesia From Science to Practice : Clinical management : Regional anesthesia

Regional anesthesia

Regional

anesthesia

We can

imagine future clinicians to prescribe treatments that would exclusively affect

a single cell type or a specific organ without spillover effects. That type of

explicit therapy would be the opposite to general anesthesia, the name of which

implies generalized effects of the anesthetic drugs. Indeed, anesthetics

delivered via the lungs or by intravenous injection flood all organs in the

body, causing numerous undesired effects. How much better to pinpoint the

effect with regional anesthesia. Here, we deliver the drug directly to the

nervous tissue where we hope to cause a specific effect. We are closer to the

ideal but not quite in heaven because we still have to contend with side

effects that arise when the anesthetic drug appears in the circulation. We also

lack the specificity of drugs that would block only one type of fiber and spare

all others. Nevertheless, regional anesthesia provides a tool that can be used

to great advantage for many patients.

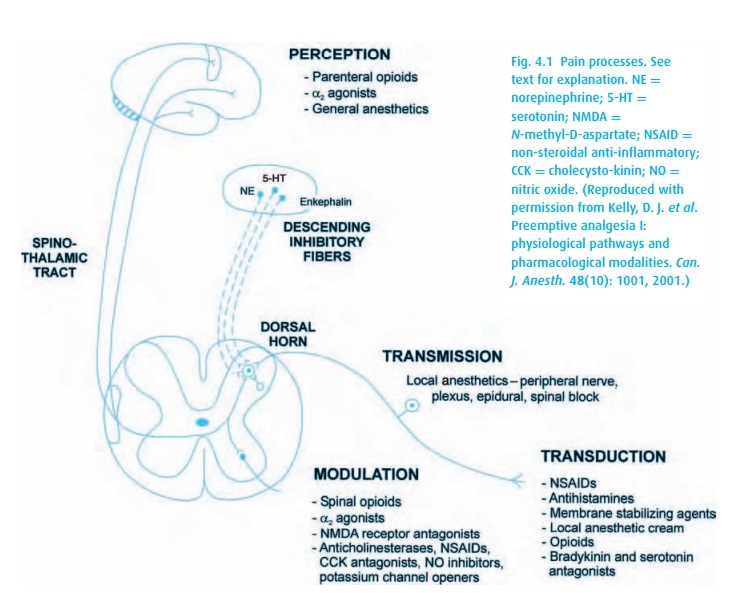

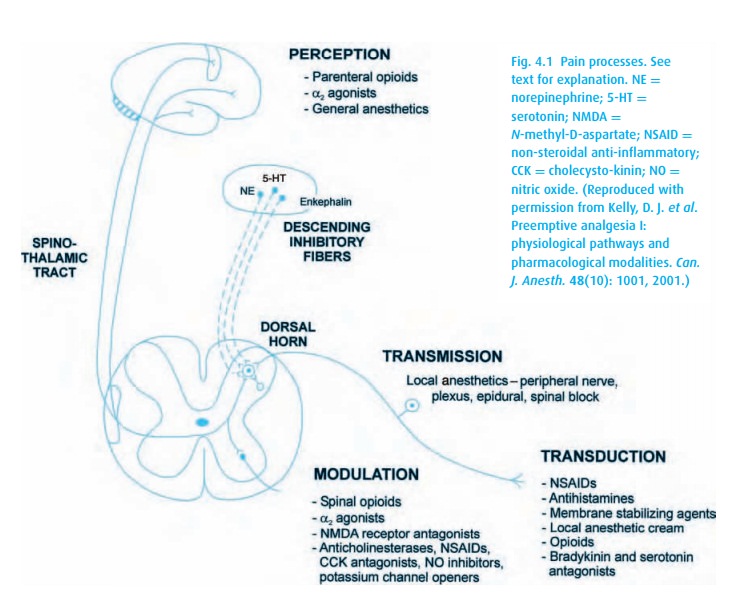

Four

distinct processes lead to the sensation of pain (Fig. 4.1):

·

Transduction Noxious stimulation of a peripheral receptor

releases localinflammatory mediators that cause changes in the activity and

sensitivity of sensory neurons. Pre-incisional

infiltration of local anesthetics effectively blocks transduction.

·

Transmission Once the noxious stimulus has been transduced,

the impulsestravel via A-delta and C fibers to the dorsal horn of the spinal

column where they synapse. The dorsal horn cells may be subject to “wind-up” or

enhanced excitability and sensitization. Transmission can be blocked with

regional anesthesia.

·

Perception Afferent fibers from the dorsal horn travel to

higher CNS cen-ters, mostly via the spinothalamic tracts. Activation of the

reticular forma-tion probably increases arousal and contributes the emotional

component of pain. Central-acting agents such as opioids alter perception.

·

Modulation Efferent pathways including inhibitory

neurotransmitters mod-ify the afferent nociceptive information.

The complexity of pain perception goes beyond this quick anatomic/physiologic summary. Strong emotional stimuli and distraction can completely block pain perception, as is often true for injuries sustained in battle (or when being eaten by a lion). Thus, in addition to the described processes of getting the signal from injured tissue to the brain, psychological factors modulate the pain experience.

While we

can interfere with the impulses traveling up the nervous pathways at any stage,

mounting evidence suggests that multi-modal and pre-emptive (before incision)

therapy can both improve immediate post-operative pain control and reduce the

risk of a subsequent chronic pain syndrome.

Transduction

of superficial noxious stimuli can be inhibited with pre-incisional local

infiltration. As the name implies, regional anesthesia involves anesthetiz-ing

a specific portion of the body, thereby preventing transmission. Because pain

sensation travels via nerves (A-delta and C fibers to be specific) from the

site of the injury to the spinal cord (dorsal columns) and then up to the

brain, the nerve impulse can be interrupted at numerous sites. Consider an

operation on the big toe. Local anesthetic infiltration suffices for only the

most superficial of procedures. For anything deeper, we make use of our

knowledge of the area’s innervation and the anatomic course of the nerves

through the body. Sensory impulses can be interrupted in several locations

including the ankle, popliteal fossa, sciatic notch, or at the spinal cord

level. The first three would be considered peripheral nerve blocks because they

block the transmission of the “pain mes-sage” before it reaches the central

nervous system. We can also block the message at the level of the central

nervous system with an epidural anesthetic (which could be a caudal block), or

a spinal (properly called a subarachnoid) block. Together, these last

approaches are called neuraxial anesthesia. And all can be effective for big

toe surgery.

When

used for operative anesthesia, we typically supplement a regional block with

sedation; the patient need not be aware during the procedure. A balance must be

struck between the patient’s comfort, and the side effects of sedation,

primarily respiratory depression. Also, all our sedatives, even midazolam

(Versed®), linger and produce a hangover effect. Therefore, the patient will

not be fully functional following the procedure, or even for the remainder of

the day. Some patients do not like this feeling and would prefer the reassuring

conversation of a caring anesthesiologist over drug-induced anxiolysis.

We may

be tempted to choose regional anesthesia for patients with cardio-vascular or

pulmonary problems, arguing that a properly conducted regional technique

stresses these systems less than does a general anesthetic. Be careful! If the

regional block is unsuccessful, if there are complications, or if the block

wears off during the operation, the patient may require emergency general

anesthe-sia and possibly also tracheal intubation. Similarly, regional

anesthesia must be used with caution in patients with a recognized “difficult

airway.” If we fear diffi-culty managing the patient’s airway, we would be

ill-advised to perform a regional anesthetic to “avoid the airway” without

adequate preparation (additional airway equipment, etc.).

Related Topics