Chapter: Medicine and surgery: Musculoskeletal system

Rheumatoid arthritis - Seropositive arthritis

Seropositive arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Definition

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic multisystem, inflammatory disorder with a characteristic symmetrical polyarthritis.

Prevalence

One to two per cent of the adult population affected.

Age

Peak age of onset 30–55 years.

Sex

2–3 F : 1 M

Geography

Prevalence varies across the world from 0.1–5%.

Aetiology

It is thought that one or more environmental trigger factors occur in a genetically susceptible individual setting up a sustained inflammatory response.

· Twin studies demonstrate a significantly higher concordance in monozygotic compared with dizygotic twins.

· Hormonal factors are implicated, possibly the effects of oestrogen on T cell function, as females are affected more than males and there is a tendency for the disease to become quiescent during pregnancy. This sex difference diminishes after the menopause reinforcing the possibility of a role for sex hormones.

· The DR region of HLA appears particularly important in the susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis. Sixty per cent of patients who develop rheumatoid arthritis have DR4. Conversely certain HLA patterns appear to be protective.

· Infective agents have been suggested as triggering stimuli, including Proteus mirabilis, Mycoplasma, Epstein–Barr virus, parvovirus and various retro-viruses.

Pathophysiology

T cells: Antibody-mediated activation of T cells triggers a more generalised T cell activation. This may cause an inflammatory response to self-antigens (type II collagen, gp39) within the synovium in the presence of costimulatory factors found in abundance in rheumatoid tissue. Cytokine cascades result in a combination of angiogenesis and cellular influx, leading to transformation of the synovium with the ability to invade cartilage and connective tissue. The transformed synovium may also activate osteoclast-mediated bone erosion.

Synovitis: Early disease is characterised by synovial inflammation and a cellrich effusion within the joint causing swelling and pain. Neutrophils predominate within the effusion and release high levels of proteolyic enzymes, causing significant damage.

Rheumatoid factors are autoantibodies to the Fc portion of IgG; they may be of any antibody class. Routine serological testing detects IgM rheumatoid factor. These factors undergo a maturation of affinity for Fc and tend to form lattice-like complexes found throughout the tissues of the rheumatoid joint. It is thought that they provoke further inflammation and activate the complement system. Patients who test positive for IgM rheumatoid factor have a more severe pattern of joint damage.

Long-standing inflammation and effusion distends the joint capsule causing laxity of the ligaments. The overall result is joint instability and continued use leads to joint deformity.

After a variable period, synovial inflammation may become quiescent. Deformities, if already present, may continue to deteriorate through secondary degenerative changes.

Clinical features (articular)

Classically, rheumatoid arthritis presents as an insidious, progressive, symmetrical polyarthritis with pain, and stiffness particularly after periods of inactivity, swelling and limitation of joint movement. Occasionally a more rapid onset and progression is seen. Fifty per cent of patients presenting with episodic monoarthritis (palindromic rheumatism) will develop rheumatoid arthritis over the subsequent months or years.

· Hands and wrists: Initially there is muscle wasting and involvement of metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints. Later there is subluxation at metacarpal phalangeal joints and ulnar deviation of fingers. Characteristic fixed flexion (Boutonniere)` or hyperextension (swan neck) deformities develop at the proximal interphalangeal joints. Tender swelling of the ulnar styloid, subluxation and deviation of the hand may occur. Carpal tunnel syndrome can occur.

· Feet and ankles: These are affected in 50% of cases, usually developing a few years after onset. Swelling of the metatarsal phalangeal joints progresses to hammer toe deformities with associated ulceration due to pressure over the metatarsal heads.

· Knees are affected with severe effusions, Baker’s cyst formation, quadriceps wasting, flexion deformities and lateral angular deviation.

· Cervical spine inflammation and bone damage results in joint instability and risks atlantoaxial subluxation with resulting cervical myelopathy.

· Other joints involved include the temporomandibular joint causing a stiff painful jaw and the cricoarytenoid joint causing hoarse voice and inspiratory stridor.

· There is often associated muscle weakness and generalised osteopenia due to immobility, which may be further exacerbated by treatment with steroids.

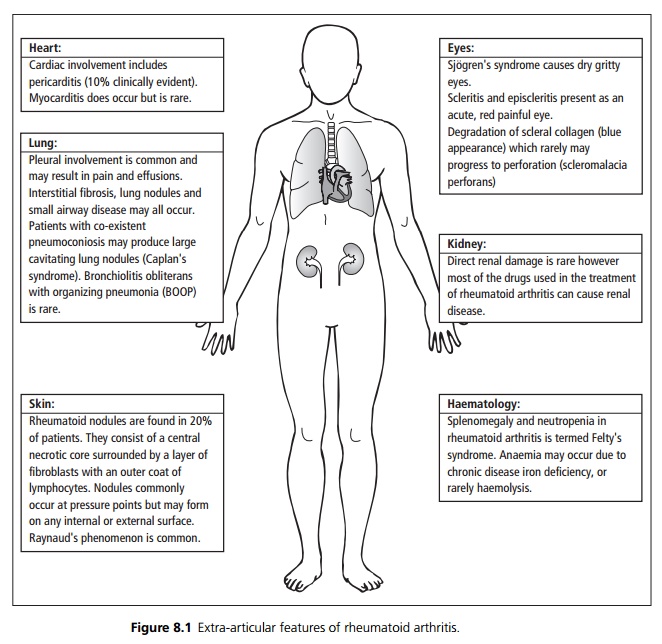

Clinical features (extra-articular)

See Fig. 8.1.

Investigations

· Blood: Anaemia (usually normochromic normocytic), with raised inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP).

· Immunology: IgM rheumatoid factor is present in 70%.

· X-ray: Early changes include soft tissue swelling, periarticular osteopenia and marginal erosion of bone. Later there is progressive loss of joint space, more extensive erosive changes and bone destruction, joint subluxation and secondary degenerative changes.

Management

Treatment strategies are multimodal and include physical interventions, symptom-controlling drugs, steroids, disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD), anti-cytokines and surgery.

· Non-pharmacological interventions include patient education, physical therapy, psychological support (e.g. patient support groups), occupational therapy, nutritional and dietary advice, appliances and footwear.

· Symptom control is generally with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which reduce pain and stiffness (ibuprofen, indomethacin, diclofenac, etc.) These have not been shown to prevent joint erosions but they can result in greater joint movement.

· Cox II inhibitors should be used in preference to standard NSAIDs in patients who are at high risk of developing serious gastrointestinal adverse effects (e.g. patients over 65 years of age, those using other medications that increase the risk of upper GI bleeding or those requiring a prolonged course of maximal dose NSAIDs). Cox II inhibitors are relatively contraindicated in patients with cardiovascular disease, a previous history of peptic ulcer disease or previous GI bleeding.

· Oral, intravenous or intra-articular steroids are used to suppress inflammation, and may be administered. High doses may be required at times of exacerbation, but because of side effects, doses should be gradually reduced and stopped if possible once the disease is quiescent.

· Disease modifying antirheumatic drugs: Patients with rheumatoid arthritis should be treated with DMARDs soon after diagnosis, as these have been shown to improve prognosis. They act to ameliorate symptoms and slow progression of structural damage. Methotrexate is normally used as first line, other agents include sulphasalazine, gold and hydroxychloroquine. Combinations of DMARDs are increasingly used. Onset is slow, 10–20 weeks, and all have some degree of toxicity.

· Tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors (etanercept and infliximab) are used in patients with persistently active rheumatoid arthritis that has not responded adequately to at least two DMARDs, including methotrexate.

· Anti-cytokines including anti-IL-1 and anti-IL-6 are undergoing evaluation.

· Because of immobility and steroid therapy patients with rheumatoid arthritis are at high risk for development of osteoporosis. Most patients should be treated with calcium and vitamin D supplementation. Bisphosphonate therapy should be considered in high-risk patients.

Surgical management aims to help with symptom control and maximise joint function. Procedures include the following:

i. Synovectomy, which is the removal of excessive synovial swelling from joints and tendons, may help to reduce pain and stiffness in early disease.

ii. Tendon repair and transfer is used particularly in the wrist and hand.

iii. Excision arthroplasty (limited joint excision) or arthrodesis (joint fusion) may be performed for intractable pain at the elbow or wrist; however, there is an inevitable loss of function. Atlantoaxial subluxation may require surgical stabilisation.

iv. Joint replacement has significant postoperative morbidity but can be an effective longer term treatment.

Prognosis

The disease generally progresses insidiously in the majority of cases although most patients experience periods of exacerbation and quiescence.

Related Topics