Chapter: Medicine and surgery: Respiratory system

Respiratory failure

Respiratory failure

Definition

Respiratory failure is defined as a fall in the arterial oxygen tension below 8 kPa. Carbon dioxide tension defines respiratory failure into type I (normal or low pCO2) and type II (pCO2 above 6 kPa).

Aetiology/pathophysiology

Type I failure, sometimes called ‘acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure’, is usually due to mismatch between ventilation and perfusion or right to left shunts. It can occur in any respiratory disease most commonly acute exacerbations of asthma or COPD, pulmonary oedema, pneumonia, pulmonary embolus and fibrosing alveolitis. Hyperventilation frequently leads to a low pCO2.

Type II failure, sometimes called ‘ventilatory failure’, is due to alveolar hypoventilation such that the carbon dioxide produced by tissue metabolism cannot be adequately removed and pCO2 rises. If the failure is chronic the patient with a type II respiratory failure will lose sensitivity to a raised carbon dioxide and therefore rely solely on hypoxic respiratory drive. If aggressive oxygen therapy is initiated the level of oxygen will rise and the respiratory drive is diminished, leading to further decreased ventilation which may be fatal. The most common cause of type II respiratory failure is chronic obstructive airway disease, other causes include any severe respiratory disease, failure of respiratory effort, e.g. central drive depression, chestwall disease such as deformity and neuromuscular disease such as myasthenia.

Clinical features

In a patient with a normal haemoglobin central cyanosis is visible when the pO2 falls below 6.7 kPa. Hypercapnia causes a flapping tremor of the outstretched hands, a bounding pulse, vasodilation, increased agitation, then confusion, drowsiness and coma. Other signs include the use of accessory muscles of respiration, tachypnoea, tachycardia, sweating and inability to speak in full sentences.

Complications

Pulmonary hypertension due to hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. With time the arteries undergo a proliferative change leading to irreversible pulmonary circulation changes. There is increased afterload on the right side of the heart leading to cor pulmonale.

Polycythaemia results from hypoxia, it causes an increase in blood viscosity and predisposes to thrombosis.

Investigations

Blood gas monitoring is the most important initial investigation to establish the type of failure and will dictate the mode of oxygen therapy.

Management

Acute or acute on chronic respiratory failure

Treat any reversible underlying cause:

Oversedation or opiate overdose by stopping or reversing sedation (e.g. flumazenil for benzodiazepines, naloxone for opiates).

Pulmonary oedema with diuretics.

Asthma by bronchodilators and corticosteroids. Pneumonia with appropriate antibiotics.

Pneumothorax or pleural effusion by aspiration or drainage.

COPD with bronchodilators, corticosteroids and antibiotics.

Controlled oxygen therapy:

In patients who have a raised pCO2 > 6kPa, oxygen therapy can potentially worsen the situation, because of the patient’s dependence on hypoxic drive. Controlled 24–28% oxygen is given by Venturi mask and arterial blood gases are repeated to ensure that the pO2 is rising and the pCO2 is not rising.

In patients with acute hypoxaemic failure and a normal or low pCO2, high-flow oxygen therapy can be used, but they must still be closely monitored with regular arterial blood gases to ensure that they are not tiring and developing type II failure.

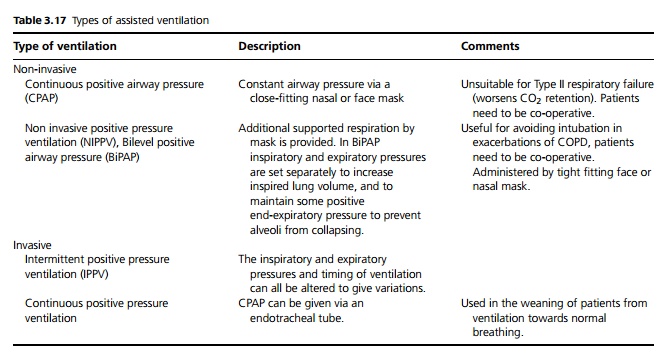

If pCO2 continues to rise or pO2 cannot be raised adequately with oxygen therapy then assisted ventilation is required, preferably before patients are completely exhausted (see Table 3.17).

Chronic respiratory failure

Long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) and in some cases non-invasive ventilation, is indicated for chronic respiratory failure. LTOT is indicated in patients with COPD who have a pO2 < 7.3 kPa when stable or a pO2 > 7.3 and <8 kPa when stable with polycythaemia, nocturnal hypoxaemia, peripheral oedema or pulmonary hypertension. 19 hours/day of oxygen 1–3 L/minute has been shown to increase survival in patients with chronic bronchitis or emphysema and respiratory failure. Patients must have stopped smoking (for safety reasons), and an oxygen concentrator needs to be installed in their home.

Prognosis

Fifty per cent of patients with severe chronic breathlessness die within 5 years, but in all stopping smoking is the most beneficial therapy.

Related Topics