Chapter: Medicine and surgery: Respiratory system

Tuberculosis - Respiratory infections

Tuberculosis

Definition

Tuberculosis (TB) is a common chronic infectious disease caused by M. tuberculosis.

Incidence

Approximately 7000 new cases a year in the United Kingdom and rising throughout Europe and the United States.

Age

Any age

Sex

M = F

Geography

Risk of contracting TB is markedly greater in developing countries, immigrants to the United Kingdom from the Asian sub-continent have a 40 times greater incidence of TB than non-immigrants. Worldwide the highest rates of tuberculosis are seen in sub-Saharan Africa, India, China and the islands of Southeast Asia. Intermediate rates of tuberculosis occur in Central and South America, Eastern Europe and Northern Africa.

Aetiology

M. tuberculosis is an acid fast aerobic bacillus that grows slowly. It is spread by coughing up of live bacilli after invasion of the disease into a main bronchus (open tuberculosis), which are then inhaled.

The rising prevalence and mortality of tuberculosis is thought to be related to the following:

· Poverty and crowded conditions particularly in urban environments.

· Relaxation of disease control programmes in the mid-twentieth century when TB was declining.

· HIV co-infection.

· The emergence of multiple drug resistance due to non-compliance with medication.

Groups particularly at risk include the elderly, the very young, alcoholics, immunosuppressed, e.g. organ transplant patients, chronic lung disease patients and hospital workers.

Pathophysiology

The cell wall of Mycobacterium contains complex lipids and glycolipids which sensitise T-cells to produce abundant cytokines, which recruit macrophages (a Type IV hypersensitivity immune response). The macrophages can phagocytose the organisms, but mycobacterial cell wall components interfere with the fusion of the lysosomes with the phagocytic vacuole, so that the bacteria can survive intracellularly.

The most common pattern of TB is a primary pulmonary infection:

· The mycobacteria are inhaled into the alveolar spaces of the lung. Conditions for growth are most favourable just below the pleura in the apex of the upper lobe or the apical lobe of the lower lobe. Here the inflammatory process forms the ‘Ghon focus’ usually just beneath the pleura. Bacteria spread to the draining lymph nodes at the lung hilum, and excite an immune response there also. This pattern forms the primary complex with infection at the periphery of the lung and enlarged peribronchial lymph nodes.

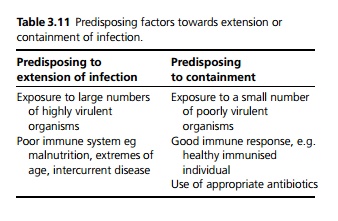

· The outcome of the primary infection depends on the balance between the virulence of the organism and the strength of the host response (see Table 3.11). If the host can mount an active cell mediated immune response the infection may be completely cleared.

· In the vast majority of cases there is an intermediate response and the activated macrophages aggregate and wall off a central area of caseous (cheeselike) necrosis. These are called granulomas or tubercles. Collagen is deposited around these, often becoming calcified. Twenty per cent of these tubercles contain viable mycobacteria, but clinically the infection becomes latent.

· If the immune response is very poor, there is progression of the caesating granulomas in the lymph nodes which erode into a bronchus or blood vessel causing further dissemination. This is called a ‘progressive primary infection’. Occasionally the Ghon focus may rupture through the pleura causing a tuberculous pleurisy.

Secondary tuberculosis

· Secondary tuberculosis is a reactivation of infection occurring in a previously latently infected individual. It usually occurs due to reactivation of a healed primary lesion due to a weakening of the host defence, e.g. diabetes mellitus, malnutrition, immunosuppression (drugs, HIV). It may occur at any time from weeks up to years after the original infection. Occasionally it may be due to reinfection from an external source. It differs from primary infection in its immunopathology. The lymph nodes are rarely involved, and there is reactivation of the immune response in the tissues.

· In the lung, the bacteria have a preference for the apices (higher pO2), and form an apical lung lesion known as an Assmann focus. It begins as a small caseating tuberculous granuloma, histologically similar to the Ghon focus, with destruction of lung tissue and cavitation. T cells are reinduced by the secondary infection, with activation of macrophages, and exactly as with primary TB the outcome is a balance between the virulence of the infection and the strength of the host immune system.

- In patients with a vigorous immune reaction there is healing of the apical region with collagen deposition and eventually calcification by the same process as the healing of the primary infection resulting in a latent apical fibrocaseous tuberculosis lesion.

- In patients with a poor immune response the lesion enlarges with caseous necrosis destroying lung tissue, thinning of the collagen wall and increasing the risk of erosion of a bronchus or blood vessel.

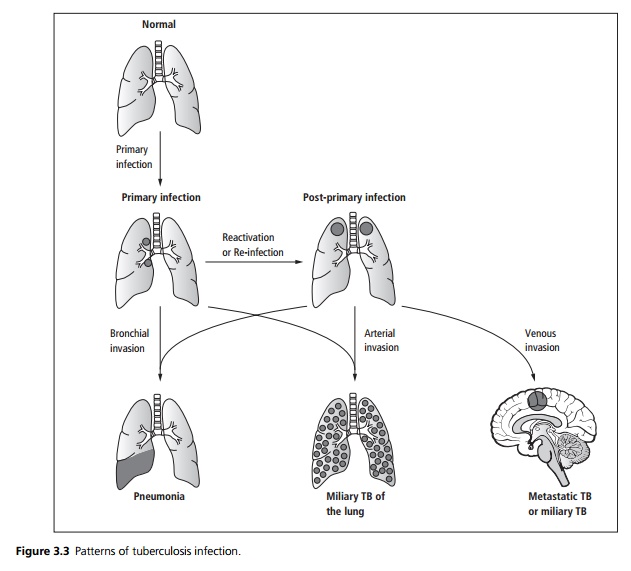

Patterns of progressive TB infection

See Fig. 3.3.

1 Tuberculous Bronchopneumonia: If an infected lymph node in primary tuberculosis, or an enlarging secondary tuberculous lesion erodes into a bronchus, tuberculous caseous material containing live tubercle bacilli spreads infection throughout that segment of lung. Coughing disperses these bacilli into the atmosphere, transmitting TB to other people. Without treatment, extensive caseating lesions develop rapidly, leading to a high mortality. This disease is sometimes called ‘galloping consumption’.

2 Miliary Tuberculosis: If an enlarged caseous node erodes into a pulmonary artery the entire lung becomes infected by miliary dissemination with multiple small tubercles. If a lesion erodes a pulmonary vein, there may be systemic miliary dissemination, for example to the meninges, spleen, liver, the choroid and the bone marrow.

3 Metastatic Tuberculosis: If there is systemic dissemination but only a few bacteria are dispersed and the patient mounts a good immune response, organisms may settle in only one or two organs such as adrenal glands, a kidney, bone, joints, brain and meninges or the reproductive tract. There they may remain dormant, reactivating many years later as single organ disease. By that time there may be no evidence of tuberculosis elsewhere.

Clinical features

1 Primary tuberculosis is usually asymptomatic, occasionally there may be a vague pyrexial illness some-times associated with respiratory symptoms such as a dry cough. The hypersensitivity reaction may produce a transient pleural effusion or erythema nodosum.

2 Secondary pulmonary tuberculosis presents typically with a gradual onset of tiredness, malaise, anorexia and loss of weight over weeks or months. The outstanding features are fever (drenching night sweats are rare) and cough productive of mucoid, purulent or blood stained sputum. A pleural effusion or pneumonia may be the presenting sign, chest signs are often absent and finger clubbing is only evident in late disease.

3 Miliary tuberculosis may present in a non-specific manner with vague ill health, weight loss and fever. As dissemination progresses there may be tuberculous meningitis, choroidal tubercles seen in the eye and hepatosplenomegaly.

Microscopy

The characteristic lesion, the tubercle (granuloma) consists of a central area of caseous tissue necrosis within which are viable mycobacteria. This central area is surrounded by a layer of activated macrophages and occasional multinucleate macrophages (Langerhans’ giant cells). Around the macrophage zone is a collar of lymphocytes and an outer coating of fibroblasts.

Complications

Fungal infection of cavitated areas of old TB infection forming a mycetoma.

An enlarged lymph node may compress a bronchus, causing collapse of a segment or lobe of the lung. This usually heals spontaneously but occasionally may persist giving rise to bronchiectasis particularly of the middle lobe (Brock’s Syndrome).

Metastatic TB: Bone marrow invasion may lead to a pancytopenia. Bone involvement may lead to pathological fractures, particularly of the spine together with a paravertebral abscess. Tuberculous meningitis, tuberculous peritonitis or tuberculous pericarditis may occur.

Investigations

An abnormal chest X-ray is often found incidentally in the absence of symptoms, but it is very rare for a case of pulmonary tuberculosis to be present if the chest X-ray is completely normal. The X-ray shows patchy or nodular shadowing in the upper zone with fibrosis and loss of volume; calcification and cavitation may also be present. There may be calcification in the pericardial sac. In miliary TB the chest X-ray may be normal, as tubercles are not visible until they are 1–2 mm.

TB can mimic almost any disease, radiographically, so confirmation of the diagnosis must be by staining and culture of material such as sputum, early morning urine samples, cerebrospinal fluid, bronchoscopic washings, pleural, transbronchial, lymph node, or bone marrow solid organ biopsy.

Microscopy with Ziehl–Nielsen staining or auramine fluorescent stain for acid fast bacilli (AFB). Rapid results can be obtained with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and DNA probes, which are highly sensitive; however, they may be positive with no active disease. Formal culture of material is the only way of accurately determining virulence and antibiotic sensitivity and should be attempted in every case, results may take 4–6 weeks.

HIV testing should be performed in all patients diagnosed with TB, even those without known risk factors, as patients with HIV are much more likely to have systemic organ involvement, relapse after treatment and may need lifelong treatment with isoniazid to prevent reactivation. They will also benefit from HIV specific treatment to improve their immune response.

Tuberculin testing is used for contact tracing and prior to vaccination, it is used to assess exposure and sensitisation to TB. It relies on the hypersensitivity reaction, and is rarely helpful in the diagnosis of tuberculosis:

i. The Tine test and Heaf test are for screening: 4/6 point needles coated with old tuberculin are used to puncture the skin, 72 hours after the test a hypersensitivity reaction is present. If the spots are confluent, the test is positive, indicating exposure. In an immunised adult no TB treatment is required as long as there is no evidence of infection.

ii. The Mantoux test involves injecting a purified protein derivative intra dermally. The reaction is read at 48–72 hours and is said to be positive if the induration is 10 mm or more in diameter, negative if less than 5 mm.

If the test is positive with a low concentration of purified protein derivative this can indicate active infection requiring treatment. In an immunocompromised host (such as chronic renal failure, lymphoma or HIV) or patients with miliary TB, the tests may be falsely negative.

Management

· Hospitalisation is required for severely ill patients or where compliance is a particular problem.

· Standard regimen is with 2 months of rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol and pyrazinamide, and a further 4 months of rifampicin and isoniazid alone. These are taken 30 minutes before breakfast to aid absorption.

· Multiresistant strains require sensitivity assessment and should be treated with three drugs to which the organism is sensitive for a full 6 months to avoid development of further resistance.

Prevention

In the United Kingdom, vaccination with BCG (Bacille Calmette–Guerin)´ has been given to Heaf negative 12 year olds since 1954. It is also offered to infants up to 6 weeks after birth (without prior skin testing) in areas with a high incidence of tuberculosis. Contact tracing of cases is essential for screening of all close family members and individuals who share kitchen and bath-room facilities by history, chest X-ray and tuberculin test.

Patients with chest X-ray evidence of previous TB who become immunosuppressed, e.g. renal dialysis, steroid treatment or organ transplant, may have daily isoniazid treatment to prevent reactivation of latent infection.

Prognosis

Five per cent of patients do not respond to therapy, only 1% due to resistance, the remainder due to failed compliance.

Related Topics