Chapter: Medicine and surgery: Respiratory system

Asthma - Obstructive lung disorders

Obstructive lung disorders

Asthma

Definition

A disease with airways obstruction (which is reversible spontaneously or with treatment), airway inflammation and increased airway responsiveness to a number of stimuli.

Incidence

20% of children, 5–14% of adults, increasing in prevalence.

Age

Can present at any age, predominantly in children.

Sex

M > F under 16 years, F > M over 16 years.

Geography

Varies, e.g. rare in underdeveloped countries.

Aetiology

Asthma can be classified as follows, although the division is not always clearcut:

1. Extrinsic asthma where there is an external cause

- It is allergy based and commonly presents in young atopic individuals.

- Atopy (asthma, eczema, hay fever and other allergies) has a familial component, it describes a disease manifestation related to the development of IgE antibodies against environmental antigens.

- Common domestic allergens include proteins from house-dust mites, pets and airborne fungi.

2. Intrinsic asthma tends to present later in life. There is no identifiable allergic precipitant.

3. Occupational asthma is a particular type of extrinsic asthma, which may occur in both atopic individuals (who are more at risk) or non-atopic individuals.

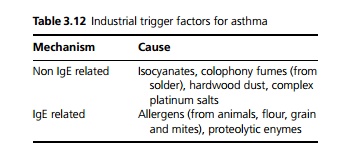

- Some industrial trigger factors are shown in Table 3.12. Patients with occupational asthma from the listed causes are entitled to compensation under industrial injuries legislation in the United Kingdom.

- For all patients, non-specific irritant trigger factors include viral infections, cold air, exercise, emotion, atmospheric pollution, dust, vapours, fumes and drugs particularly nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories and β-blockers.

Pathophysiology

The clinical picture of asthma results from mixed acute and chronic inflammation leading to bronchoconstriction, mucosal oedema and secretion of mucus into the lumen of the bronchi. With time this repeated stimulation causes hyperplasia of the smooth muscle and mucus glands within the bronchial wall as well as airway wall fibrosis. The pathophysiology is not yet fully understood. Asthma is a complex mixture of acute and chronic inflammation.

- Acute inflammation is largely mediated by allergen crosslinking of IgE on mast cells, leading to the release of mediators such as histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, proteolytic enzymes and cytokines.

- The chronic inflammation is mediated by T cells producing type 2 cytokines (TH2). IL-5 recruits eosinophils, IL-4 and IL-13 lead to IgE synthesis and mucous secretion.

- Eosinophils are also important, secreting mediators of acute and chronic inflammation including proteolytic enzymes.

- Neutrophils are prominent in severe and virusinduced asthma. They secrete mediators of acute and chronic inflammation including enzymes and oxygen radicals.

- Epithelial cells from the bronchi are activated by allergens, viruses and air pollution and release chemotactic factors that recruit and activate inflammatory cells.

- All of the above cell types release mediators of chronic inflammation recruiting and activating fibroblasts leading to airway fibrosis. They also lead, through mechanisms which are not yet clearly defined, to bronchial hyperresponsiveness – an exaggerated bronchoconstrictor response to non-specific insults to the airways.

The pattern of airway reaction following inhalation of an allergen:

· An acute reaction occurring within minutes, peaking at ∼20 minutes after inhalation (the acute inflammatory response).

· A late reaction occurring 4–8 hours after inhalation (the chronic inflammatory response).

· A dual phase response incorporating both acute and late phase reactions (the mixed acute and chronic inflammatory response that is characteristic of asthma).

Clinical features

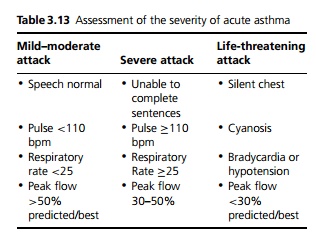

An asthma attack is characterised by rapid inspiration, slow and laboured expiration and polyphonic wheezes in all lung fields heard on expiration. Because of the potential severity of asthma patients require rapid assessment and intervention. An acute asthma attack is classified according to clinical severity (see Table 3.13).

In the long-term management of an asthmatic patient it is important to assess the degree of control that the patient’s symptoms are under. Night-time waking, early morning wheeze, acute exacerbations in the preceding year, previous admissions to intensive care and a high requirement for bronchodilator therapy are all markers of poor control.

Complication

Pneumothorax, surgical emphysema due to rupture of alveoli and pneumomediastinum.

Investigations

The PEF (peak expiratory flow) is the most commonly used investigation in asthma. During an attack there is a marked reduction in all expiratory flow indices. In chronic asthma there is a characteristic diurnal variation with PEF >15% lower in early morning as well as day to day variation of >15%. For diagnosis and management patients may therefore be asked to fill in PEF charts with measurements taken AM and PM (prior to any inhaler therapy).

The simplest diagnostic test for asthma is to show a 15% improvement in PEF or forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) with an inhaled bronchodilator. However, the test may be falsely negative if the asthma is controlled, in remission, or chronically very severe. If there is diagnostic difficulty in patients with mild symptoms or just cough, exercise tests or peak flow diary card recordings as above. Occasionally, a trial of oral corticosteroids for 2 weeks can be used. Skin tests are used to identify specific allergens and serum can be taken for total and specific IgEs.

Management

Management can be divided into acute and long-term management.

Long-term management

Asthma is a variable condition which often changes so treatment must be regularly reviewed.

Allergen avoidance can be advised, e.g. avoid pets, soft toys and dust and employ house dustmite avoidance mechanisms. However these rarely have a major impact on disease.

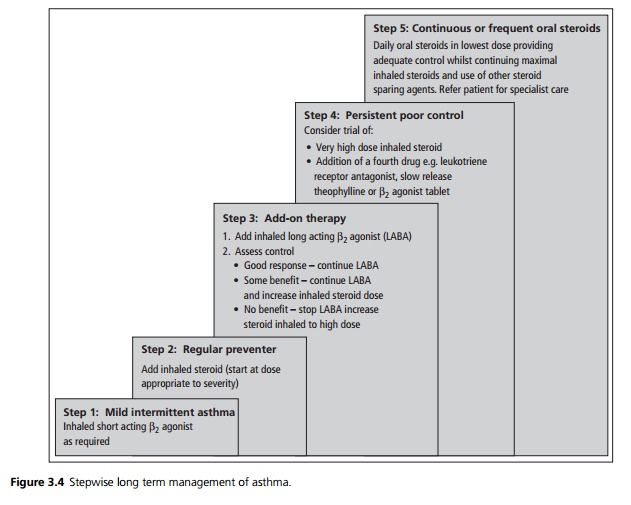

Drug therapy includes: short acting β2 agonists for

short term bronchodilation; inhaled steroids for anti-inflammatory activity; long acting β2 agonists for long term bronchodilation; anti leukotrienes, theo-phyllines and other agents with additional activities (see Fig. 3.4).

Except in mild intermittent asthma antiinflammatory therapy should be started early and must be used regularly. Once disease control is achieved the steroid dose is reduced under regular review to the minimum dose required to maintain disease control.

Long acting β2 agonists have been shown to produce better-sustained control. Their introduction is better than increasing inhaled steroids beyond a moderate dose, both in terms of greater effect and reduced side effects.

Self-management plans in which the patient adjusts

medications according to instructions relating to their PEF and/or symptoms have been shown to improve patient education, treatment compliance, disease control and acute exacerbations. They are strongly indicated in moderate to severe asthma.

Consideration should be given to stepping down treatment after a period of stability, but steroids should not be reduced more frequently than every 3 months.

Acute management

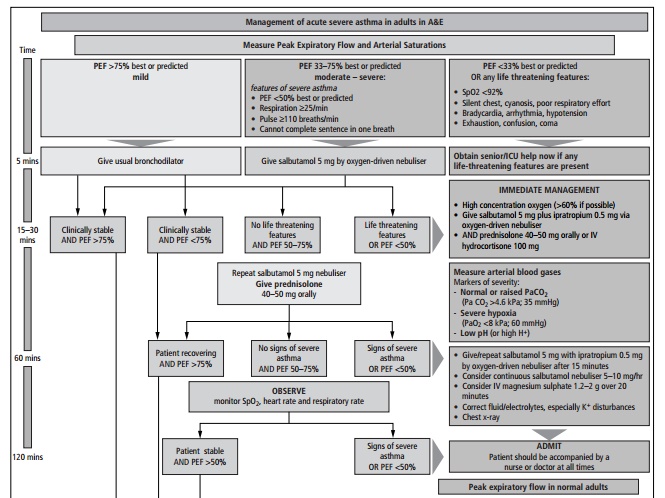

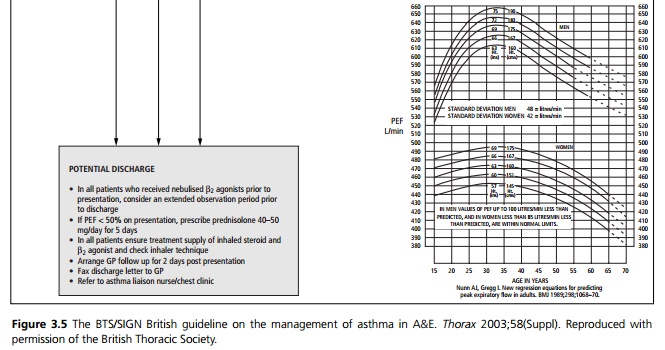

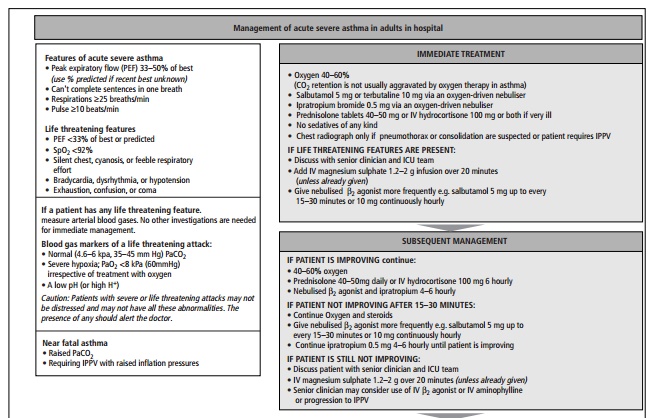

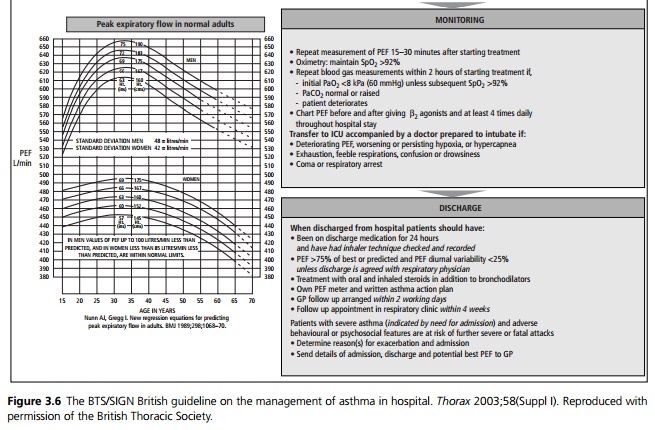

This should follow the BTS/SIGN British Guidelines (see Figs. 3.5 and 3.6).

Prognosis

Most children and teenagers with asthma improve as they get older, although asthma may recur in adult life. All patients should be advised not to smoke and to avoid potential work allergens. Mortality is ∼2000 per year in the United Kingdom and is reduced by inhaled steroid therapy.

Related Topics