Chapter: Psychology: Memory

Psychology: Retrieval

RETRIEVAL

When we learn, we transfer new

information into our long-term store of knowl-edge, and then we consolidate

this newly acquired information. But we still need one more step in this

sequence, because memories provide no benefit for us if we can’t retrieve them

when we need them. Hence retrieval—the

step of locating and activating information in memory—is crucial. Moreover, the

success of retrieval is far from guaranteed, and many cases of apparent

“forgetting” can be understood as retrieval

failures—cases in which the information is in your memory, but you fail

tolocate it.

Partial Retrieval

Retrieval failure can be

documented in many ways—including the fact that sometimes we remember part of the information we’re seeking,

but we can’t recall the rest. This pat-tern can arise in many circumstances,

but it’s most clearly evident in the phenomenon psychologists call the tip-of-the-tongue (TOT) effect.

Try to think of the word that

means “to formally renounce the throne.” Try to think of the name of the

Russian sled drawn by three horses. Try to think of the word that describes

someone who, in general, does not like other people. Chances are that, in at

least one of these cases, you found yourself in a frustrated state: certain you

know the word but unable to come up with it. The word was, as people say, right

on the “tip of your tongue.”

People who are in the so-called

TOT state can often remember roughly what the word sounds like—and so, when

they’re struggling to recall abdicate,

they might remember abrogate or annotate instead. Likewise, they can

often recall what letter the word begins with, and how many syllables it has,

even though they can’t recall the word itself (A. Brown, 1991; R. Brown &

McNeill, 1966; Harley & Bown, 1998; L. James & Burke, 2000; B.

Schwartz, 1999).

Similar results have been

obtained when people try to recall specific names—for example, what is the

capital of Nicaragua? Who was the main character in the movie TheMatrix? In response to these

questions, people can often recall the number of syllablesin the target name

and the name’s initial letter, but not the name itself (Brennen, Baguley,

Bright, & Bruce, 1990; Yarmey, 1973). They also can often recall related

mate-rial, even if they can’t remember the target information. (Thus, they

might remember Morpheus, but not the main character, from The Matrix; the main character, of course, was Neo. And the Russian sled is a troika;

it’s a misanthrope who doesn’t like

other peo-ple; Nicaragua’s capital is Managua.)

People in the TOT state cannot

recall the target word, but the word is certainly in their memory. If it

weren’t, they wouldn’t be able to remember the word’s sound, or its starting

letter and syllable count. What’s more, people often recognize the word when it’s offered to them (“Yes! That’s it!”).

This is, therefore, unmistakably a case of retrieval failure—the information is

preserved in storage, but for various reasons it is inaccessible.

Effective Retrieval Cues

Retrieval failure is also clearly

the problem whenever you seem to have forgotten some-thing, but then recall it

once you’re given an adequate retrieval

cue. A clear illustration of this pattern often arises when someone returns

to his hometown after a long absence. This return can unleash a flood of

recollection, including the recall of many details the person thought he’d

forgotten long ago. Since these memories do surface, triggered by the sights

and sounds of the hometown, there’s no doubt about whether the memories were

established in the first place (obviously, they were) or lost from stor-age

(obviously, they weren’t). Only one explanation is possible, therefore, for why

the memories had been unavailable for so many years prior to the person’s

return to his hometown. They were in memory, but not findable—exactly the

pattern we call retrieval failure.

Why do some retrieval cues (but

not others) allow us to locate seemingly long-lost memories? One important

factor is whether the cue re-creates the context in which the original learning

occurred. This is obviously the case in returning to your hometown— you’re back

in the context in which you had the experiences you’re now remembering. But the

same broad point can be documented in the lab; and so, for example, if an

indi-vidual focused on the sounds of words while learning them, then she would

be well served by reminders that focus on sound (“Was there a word on the list

that rhymes with log? ”); if she

focused on meaning while learning, then the best reminder would be one that

again draws her attention toward meaning (“Was one of the words a type of

fruit?”; R. Fisher & Craik, 1977).

The explanation for this pattern

lies in our earlier discussion of memory connec-tions. Learning, we suggested,

is essentially a process of creating (or strengthening) connections that link

the to-be-remembered material to other things you already know. But what

function do these connections serve? When the time comes to recall something,

the connections serve as retrieval paths—routes

that lead you back to the desired information. Thus, if you noticed in a movie

that Jane’s smile caused Tarzan to howl, this will create a link between your

memory of the smile and your memory of the howl. Later on, thinking about the

smile will bring Tarzan’s howl into your thoughts—and so your retrieval is

being guided by the connection you estab-lished earlier.

On this basis, let’s think

through what would happen if a person studied a list of words and focused, say,

on the sound of the words. This focus would establish certain

connections—perhaps one between dog

and log, and one between paper and caper. These connections will be useful if, later, this person is

asked questions about rhymes.

If she’s asked, “Was there a word

on the list that rhymes with log?”

the connection now in place will guide her thoughts to the target word dog. But the same connection will play

little role in other situations. If she’s asked, “Did any of the words on the

list name animals with sharp teeth?” the path that was established during

learning—from log to dog—is much less helpful; what she needs

with this cue is a retrieval path leading from sharp teeth to the target.

The impact of these same

retrieval cues would be different, though, if the person had thought about

meaning during learning. This focus would have created a different set of

connections—perhaps one between dog

and wolf. In this case, the “rhymes

with log?” cue would likely be

ineffective, because the person has established no connection with log. A cue that focused on meaning,

however, might trigger the target word.

Overall, then, an effective

retrieval cue is generally one that takes advantage of an already established

connection in memory. We’ve worked through this issue by point-ing to the

difference between meaning-based connections and sound-based connec-tions, but

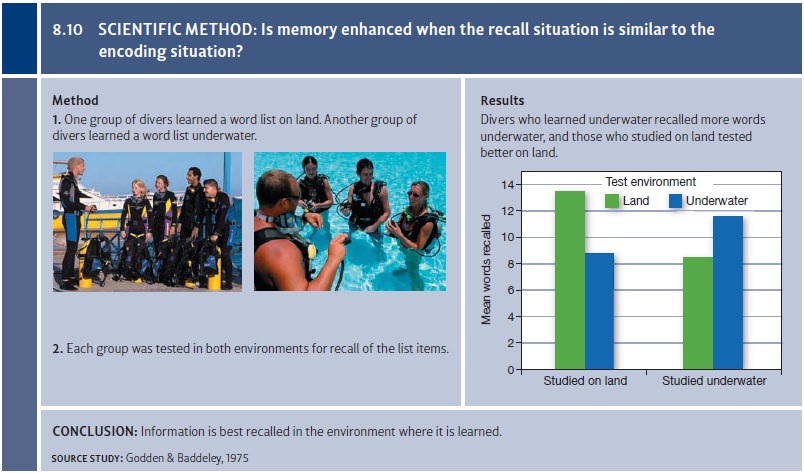

the same point can be made in other ways. In one experiment, the researchers

asked deep-sea divers to learn various materials. Some of the divers learned

the material while sitting on land by the edge of the water. Others learned the

material while 20 feet underwater, hearing the material via a special

communication set. Within each of these two groups, half of the divers were

then tested while above water, and half were tested below (Godden &

Baddeley, 1975).

Imagine that you’re a diver in

the group that learned while underwater. In this setting , the world has a

different look and feel than it does above water: The sound of your breathing

is quite prominent; so is the temperature. As a result, you might end up

thinking about your breathing (say) during learning , and this will likely

cre-ate memory connections between these breathing thoughts and the materials

you’re learning. If you are then back underwater at the time of the memory

test, the sound of your breathing will again be prominent, and this may lead

you back into the same thoughts. Once thinking these thoughts, you will benefit

from the memory connec-tion linking the thoughts to the target materials—and so

you’ll remember the mate-rials. In contrast, if you’re on land during the

memory test, then the sound of breathing is absent, and so these thoughts won’t

be triggered and the connections you established earlier will have no

influence.

We might therefore expect the

divers who learned underwater to remember best if tested underwater; this

setting increases their chances of benefiting from the memory connections they

established during learning. Likewise, the divers who learned on land should do

best if tested on land. And that’s exactly what the data show (Figure 8.10).

Related examples are easy to

find. Participants in one study were asked to read an article similar to those

they routinely read in their college classes; half read the article in a quiet

setting, and half read it in a noisy environment. When tested later, those who

read the article in quiet did best if they were tested in quiet; those who read

it in a noisy environment did best if tested in a noisy setting (Grant et al.,

1998). In both cases, par-ticipants showed the benefit of being able to use, at

time of retrieval, the specific con-nections established during learning.

In case after case, then, it’s

helpful, at the time of memory retrieval, to return to the context of learning.

Doing this will encourage some of the same thoughts that were in place during

learning, and so will allow you to take advantage of the connections link-ing

those thoughts to the target material. This broad pattern is referred to as a

benefit of context reinstatement—a

benefit of re-creating the state of mind you were in dur-ing learning.

Let’s also note that, in these

experiments, the physical setting (noisy or not; underwater or above) seems to

have a powerful influence on memory. However,

evidence suggests that the

physical setting matters only indirectly: A return to the phys-ical circumstances

of learning does improve recollection, but only because this return helps

re-create the mental context of learning—and it’s the mental context that

mat-ters. This was evident, for example, in a study in which participants were

presented with a long list of words. One day later, the experimenter brought

the participants back for an unexpected recall test that took place in either

the same room or a different one (one that differed in size, furnishings, and

so on, from the context of learning). Not surpris-ingly, recall was better for

those who were tested in the same physical environment— documenting, once

again, the benefit of context reinstatement. Crucially, though, the

investigator found a straightforward way of eliminating the difficulty caused

by an environmental change: A different group of participants were brought to

the new room; but just before the test, they were asked to think about the room

in which they had learned the lists—what it looked like, how it made them feel.

By doing so, they men-tally re-created the old environment for themselves; on

the subsequent recall test, these participants performed just as well as those

who were tested in their original room (S. Smith, 1979; S. Smith & Vela,

2001; Figure 8.11). Apparently, then, what mat-ters for retrieval is your

mental perspective, not the room you’re sitting in. If you change the physical

context without changing your mental perspective, the physical relocation has

no effect.

Encoding Specificity

The effectiveness of context reinstatement

also tells us something important about how materials are recorded in memory in

the first place. When people encounter some stim-ulus or event, they think about this experience in one way

or another; and as we’ve described, this intellectual engagement serves to

connect the new experience to other thoughts and knowledge. We’ve been

discussing how these connections serve as retrieval paths, helping people to

recall the target information, but let’s now add that this is possible only

because those connections are themselves part of the memory record. Thus,

continuing an earlier example, if people see the word dog and think about what it rhymes with, what ends up being stored

in memory is not just the word. What’s stored must be the word plus some record

of the connections made to rhyming words—otherwise, how could these connections

influence retrieval? Likewise, if people see a picture and think about what it

means, what’s stored in memory is not just the pic-ture, but a memory of the

picture together with some record of the connections to other, related ideas.

In short, what’s placed in memory

is not some neutral transcription of an event. Instead, what’s in memory is a

record of the event as understood from a

particular perspec-tive or perceived within a particular context.

Psychologists refer to this broad pattern asencoding specificity—based on the idea that what’s recorded in

memory is not just a“copy” of the original, but is instead encoded from the original (in other words, it’s trans-lated into

some other form) and is also quite specific

(and so represents the material plus

your thoughts and understanding of the material; Tulving & Osler, 1968;

Tulving & Thomson, 1973; also Hintzman, 1990).

This specificity, in turn, has

powerful effects on retrieval—that is, on how (or whether) the past is

remembered. For example, participants in one study read target words (e.g., piano) in either of two contexts: “The

man lifted the piano” or “The man tuned the piano.” These sentences led the

participants to think about the target word in a particular way, and it was

then this line of thinking that was encoded into each per-son’s memory. Thus,

continuing the example, what was recorded in memory was the idea of “piano as

something heavy” or “piano as a musical instrument.” This difference in memory

content became clear when participants were later asked to recall the target

words. If they had earlier seen the “lifted” sentence, then they were quite

likely to recall the target word if given the hint “something heavy.” The hint

“something with a nice sound” was much less effective. But if participants had

seen the “tuned” sentence, the result reversed: Now the “nice sound” hint was

effective, but the “heavy” hint was not (Barcklay, Bransford, Franks,

McCarrell, & Nitsch, 1974). In both cases, the memory hint was effective

only if it was congruent with what was stored in memory—just as the encoding

specificity proposal predicts.

This notion of encoding

specificity is crucial in many contexts. For example, imag-ine two friends who

have an argument. Each person is likely to interpret the argument in a way

that’s guided by his own position—and so he’ll probably perceive his own

remarks to be clear and persuasive, and his friend’s comments to be muddy and

evasive. Later on, how will each friend remember the event? Thanks to encoding

specificity, what each person places in memory is the argument as he understood it. As a result, we

really can’t hope for a fully objective, impartial memory, one that might allow

either of the friends to think back on the argument and perhaps reevaluate his

position. Instead, each will, inevitably, recall the argument in a way that’s

heavily colored by his initial leaning.

Related Topics