Chapter: Psychology: Memory

Psychology: Possible Subdivisions of Episodic Memory

Possible

Subdivisions of Episodic Memory

Plainly, then, we need to

distinguish semantic memory from episodic, and we need to distinguish different

types of semantic memory. Do we also need subdivisions within episodic memory?

Some theorists believe we do, granting special status, for example, to autobiographical memory—the memory that

defines, for each of us, who we are (e.g.,Baddeley, Aggleton, & Conway,

2002; Cabeza & St. Jacques, 2007). Other theorists propose that certain types of events are stored in

specialized memory systems—so that some authors argue for special status for flashbulb memories, and others suggest

special status for memories for traumatic

events.

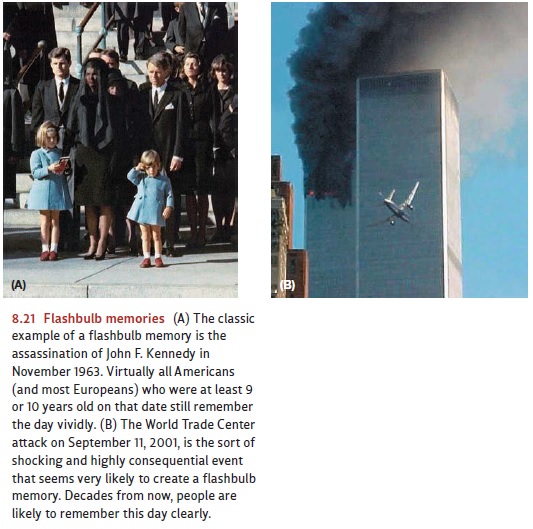

FLASHBULB MEMORIES

Each one of us encounters a wide

diversity of events in our lives. Many of these events are emotionally neutral

(shopping for groceries, or buying a new Psychology textbook), while others

trigger strong feelings (an especially romantic evening, or a death in the

family). In general, emotional episodes tend to be better remembered—more

vividly, more completely, and more accurately (e.g., Reisberg & Heuer,

2004)—and many mechanisms contribute to this effect. Among other points,

emotional events are likely to be interesting to us, guaranteeing that we pay

close attention to them; and we’ve already seen that attention promotes memory.

Emotional events are also likely to involve issues or people we care about;

this makes it likely that we’ll readily connect the event to other knowledge

(about the issues or the people)—and these connections, of course, also promote

memory. In addition, the various biological changes that accom-pany emotion

play a role—facilitating the process of memory consolidation (e.g., Buchanan

& Adolphs, 2004; Dudai, 2004; Hamann, 2001; LaBar & Cabeza, 2006;

LaBar, 2007).

Within the broad set of emotional

memories, however, our memory for some events seems truly extraordinary for its

longevity: People claim to remember these events, even decades later, “as if

they happened yesterday.” These especially vivid memories, called flashbulb memories, typically concern

events that were highly distinctive andunexpected as well as strongly

emotional. The most common examples involve emo-tionally negative events that triggered fear, or grief, or horror—such as

the memory of an early morning phone call reporting a parent’s death, or the

memory of hearing about the attack on the World Trade Center in 2001 (Figure

8.21).

The clarity and longevity of

flashbulb memories led psychologists R. Brown and Kulik (1977) many years ago

to propose that we must have some special “flashbulb mechanism” distinct from

the mechanisms that create other, more mundane memories.

The full pattern of evidence,

however, suggests that there is no such special mechanism. As one concern,

people usually talk with their friends about these remarkable events (i.e., you

tell me your story, and I tell you mine), and it’s probably this rehearsal, not

some specialized mechanism, that makes these memories so long lasting. What’s

more, flashbulb memories—like other memories—are not immune to error: In fact,

some flashbulb memories are filled with inaccuracies and represent the event in

a fashion far from the truth (see, for example, M. Conway et al., 2009;

Greenberg, 2004; Hirst et al., 2009; Luminet & Curci, 2009; Neisser, 1982a,

1986).

Moreover, the longevity of

flashbulb memories may be less extraordinary than it seems, because other, more

mundane, memories may also be extremely long lasting. One study tested people’s

memory for faces, asking in particular whether people could still identify

photos of people they’d gone to high school with many years earlier (Bahrick et

al., 1975; also see M. Conway, Cohen, & Stanhope, 1991; also see Bahrick

& Hall, 1991; Bahrick, Hall, Goggin, Bahrick, & Berger, 1994). People

who had graduated from high school 14 years earlier were still able to name

roughly 90% of the faces; the success rate was roughly 75% for people who

graduated 34 years earlier. A half-century after leaving high school, people

could still name 60% of the faces (and it’s unclear whether this small drop-off

in accuracy reflects an erosion of memory or a more gen-eral decline in

cognitive performance caused by normal aging). Clearly, therefore, even

“non-flashbulb memories” can last for a very long time.

Flashbulb memories do seem

remarkable—in their clarity, their durability, and (in some cases) their

accuracy. But these attributes are likely to be the result of rehearsal plus

the ordinary mechanisms associated with emotional remembering, and not a basis

for claiming that flashbulb memories are somehow in a class by themselves.

MEMORY FOR TRAUMATIC EVENTS

There has been considerable

controversy over a different proposal—the notion that memory for traumatic events might follow its own

rules, different from the principles governing other types of episodic memory.

Certainly, many of the principles we’ve dis-cussed apply to traumatic memory,

just as they apply to memories of other sorts. Thus, traumatic memories become

harder to recall as time goes by; and they sometimes con-tain errors, just like

all memories do. Traumatic memories are also better retained if they’re

rehearsed (thought about) once in a while. In these regards, traumatic

memo-ries seem quite similar to other sorts of episodic memory. The debate,

however, is focused on a further issue—whether trauma memories are governed by

a separate set of principles tied to how people might protect them-selves from the painful recollection of horrific

events.

Overall, how well are traumatic

events remembered? If someone has witnessed wartime atrocities or has been the

victim of a brutal crime, how fully will he remember these horrific events

(Figure 8.22)? If someone suffers through the horrors of a sexual assault, will

she be left with a vivid memory as a terrible remnant of the expe-rience? The

evidence suggests that traumatic events tend to be remembered accurately,

completely, and for many years. Indeed, the victims of some atrocities seem

plagued by a cruel enhancement of memory, leaving them with extra-vivid

recollections of the awful event (see, for example, K. Alexander et al., 2005;

Brewin, 1998; Goodman et al., 2003; McNally, 2003b; Pope, Hudson, Bodkin, &

Oliva, 1998; S. Porter & Peace, 2007; Thomsen & Berntsen, 2009). In

fact, in many cases these recollections can become part of the

package of difficulties that lead

to a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress

disorder, and so they may be horribly disruptive for the afflicted

individual .

There are, however, some striking

exceptions to this broad pattern. Researchers have documented many cases in

which people have suffered through truly extreme events but seem to have little

or no recall of the horrors (see, for example, Arrigo & Pezdek, 1997).

Thus, someone might be in a terrible car crash but have absolutely no

recollec-tion of the accident. Someone might witness a brutal crime but be

unable to recall it just a few hours later.

How should we think about this

mixed pattern? Let’s start with the outcome that’s by far more common—the

person whose trauma is remembered all too well. This outcome is probably best

understood in terms of the biological process of consolida-tion, using the

hypothesis that this process is promoted by the conditions that accom-pany

bodily arousal (Buchanan & Adolphs, 2004; Hamann, 2001). But what about the

cases of the other sort—the person with no memory of the trauma at all? In many

of these cases, the traumatic events were accompanied by physical duress, such

as sleep deprivation, head injuries, or alcohol abuse, each of which can

disrupt memory (McNally, 2003b). In still other cases, the extreme stress

associated with the event is likely to have disrupted the biological processes

(the protein synthesis) needed for establishing the memory in the first place;

as a result, no memory is ever established (Hasselmo, 1999; McGaugh, 2000;

Payne, Nadel, Britton, & Jacobs, 2004).

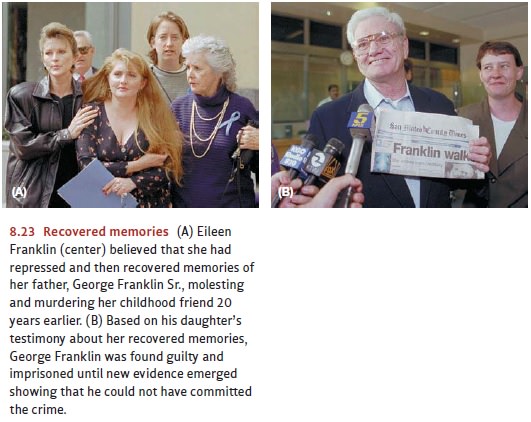

Plainly, therefore, several

factors are relevant to trauma memory. But the heated debate over these

memories centers on a further claim: Some authors argue that highly painful

memories will be repressed—that is,

hidden from view by defense mechanisms designed to shield a person from

psychological harm. In a related claim, some authors suggest that painful

events will trigger the defense of dissociation,

in which the person tries to create a sense of “psychological distance” between

themselves and the horror. In either case, the proposal is that these memories

are blocked by a specialized mechanism that’s simply irrelevant to other, less

painful, memories. According to this view, trauma memory is indeed a special

subset within the broader domain of episodic memory.

Advocates for this special status

point to several forms of evidence, including cases in which a memory seems to

have been pushed out of consciousness and kept hidden for many years but is

then “recovered” (brought back into consciousness) at some later point. This

pattern is sometimes alleged in cases of child sexual abuse: The vic-tim

represses the memory (or dissociates) and so has no recollection of the abuse

for years. Later in life, however, the victim recovers the memory, revealing at

last the long-hidden crime.

Do these cases provide evidence

for repression or dissociation, followed by a process of memory recovery? In

answering, we need to start by acknowledging that incest and childhood sexual

abuse are surely far more prevalent than many people suppose (Pipe, Lamb,

Orbach, & Cederbork, 2007). It’s also clear that some events—particularly

emo-tionally significant events—can be held in memory for a very long

time—years or even decades. We also know that it’s possible for memories to be

“lost” for years and then recovered (e.g., Geraerts et al., 2006; Geraerts et

al., 2009; Geraerts et al., 2007). On all these grounds, then, it seems

plausible that these memories of childhood abuse, hid-den for decades, may be

entirely accurate—and, indeed, provide evidence for horrid wrongdoing and

criminal prosecution.

But there are some complications here. For one thing, the pattern just described— with memories lost from view and then recovered—may not involve repression or dis-sociation at all. As an alternative, these memories might just indicate a long-lasting retrieval failure that was eventually reversed, once the appropriate memory cue came along. This would take none of the importance away from these memories: They still would reveal serious crimes, worthy of substantial punishment. But, from this perspec-tive, our explanation of these memories involves no mechanism beyond the memory processes we’ve already been discussing—and so, on this basis, the content of these memories would be distinctive in a tragic way; but the processes that create and main-tain these memories would be the same as those operating in other cases.

In addition, and far more

troubling, at least some of the “recovered memories” may in fact be

false—created through mechanisms. After all, many of these recovered memories

involve events that took place years ago, and we know that the risk of error is

greater in remembering the distant past than it is in remembering recent

events. Likewise, the evidence is clear that people can have detailed (false) recollection

of entire episodes—including highly emotional episodes—that never happened at

all. And we know that these false memories are even more likely if the per-son,

from her current perspective, regards the “remembered” event as plausible (see,

for example, Bernstein & Loftus, 2009; Chrobak & Zaragoza, 2008;

Loftus, 2005; Ofshe, 1992; Pezdek, Blandon-Gitlin, & Gabbay, 2006;

Principe, Kanaya, Ceci, & Singh, 2006). We also know that false memories,

when they occur, can be recalled just as vividly, just as confidently, and with

just as much distress as when recalling actual memories (Figure 8.23). All of

these points remind us that we cannot take the veracity of the recovered

memories for granted. Some recovered memories are very likely to be accurate, but

some are likely to be false. And, sadly, we have no means of telling which

memories are which—which provide a factually correct record of terrible

misdeeds and which provide a vivid and compelling fiction, portraying events that never happened. (For discussion of

this difficult issue, see Freyd, 1996, 1998; Geraerts et al., 2006; Geraerts et

al., 2009; Geraerts et al., 2007; Ghetti et al., 2006; Giesbrecht et al., 2008;

Kihlstrom & Schacter, 2000; Loftus & Guyer, 2002; McNally &

Geraerts, 2009; Schooler, 2001.)

The debate over recovered

memories is ongoing and has many implications— including implications for the

legal system, because these memories are sometimes offered as evidence for

criminal wrongdoing. But in the meantime, what about our initial question? Are

traumatic memories in a special category, involving mechanisms irrelevant to

other categories of episodic memory? In light of the continuing debate, the

answer remains a matter of substantial disagreement.

Related Topics