Chapter: Basic & Clinical Pharmacology : Development & Regulation of Drugs

Preclinical Safety & Toxicity Testing

PRECLINICAL SAFETY & TOXICITY

TESTING

All drugs are toxic in some individuals at

some dose. Seeking

to cor-rectly define the limiting toxicities of drugs and the therapeutic index

comparing benefits and risks of a new drug is an essential part of the new drug

development process. Most drug candidates fail to reach the market, but the art

of drug development consists of effective assessment and management of risk

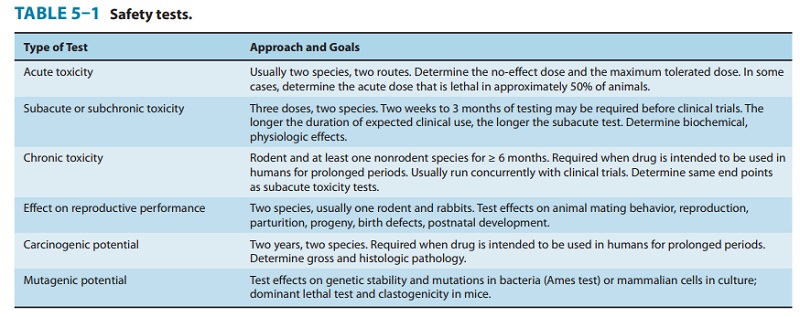

versus benefit and not total risk avoidance.Candidate drugs that survive the

initial screening procedures must be carefully evaluated for potential risks

before and during clinical testing. Depending on the proposed use of the drug,

pre-clinical toxicity testing includes most or all of the procedures shown in

Table 5–1. Although no chemical can be certified as completely “safe” (free of

risk), the objective is to estimate the risk associated with exposure to the

drug candidate and to consider this in the context of therapeutic needs and likely

duration of drug use.The goals of preclinical toxicity studies include

identifying potential human toxicities, designing tests to further define the

toxic mechanisms, and predicting the most relevant toxicities to be monitored

in clinical trials. In addition to the studies shown in Table 5–1, several

quantitative estimates are desirable. These include the no-effect dose—the maximum dose at which a speci-fied toxic effect

is not seen; the minimum lethal dose—the

small-est dose that is observed to kill any experimental animal; and, if

necessary, the median lethal dose (LD50)—the

dose that kills approximately 50% of the animals. Presently, the LD50

is estimated from the smallest number of animals possible. These doses are used

to calculate the initial dose to be tried in humans, usually taken as one

hundredth to one tenth of the no-effect dose in animals.

It

is important to recognize the limitations of preclinical test-ing. These

include the following:

1.

Toxicity testing is time-consuming and expensive. Two to 6 years may be

required to collect and analyze data on toxicity before the drug can be

considered ready for testing in humans.

2.

Large numbers of animals may be needed to obtain valid pre-clinical data.

Scientists are properly concerned about this situ-ation, and progress has been

made toward reducing the numbers required while still obtaining valid data.

Cell and tis-sue culture in vitro methods and computer modeling are

increasingly being used, but their predictive value is still lim-ited. Nevertheless,

some segments of the public attempt to halt all animal testing in the unfounded

belief that it has become unnecessary.

3.

Extrapolations of therapeutic index and toxicity data from animals to humans

are reasonably predictive for many but not for all toxicities. Seeking an

improved process, a Predictive Safety Testing Consortium of five of America’s

largest pharma-ceutical companies with an advisory role by the Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) has been formed to share internally developed laboratory methods

to predict the safety of new treatments before they are tested in humans. In

2007, this group presented to the FDA a list of biomarkers for early kid-ney

damage.

4.

For statistical reasons, rare adverse effects are unlikely to be detected in

preclinical testing.

Related Topics