Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment of Respiratory Function

Physical Assessment of the Upper Respiratory Structures

PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT OF THE UPPER RESPIRATORY STRUCTURES

For

a routine examination of the upper airway, only a simple light source, such as

a penlight, is necessary. A more thorough exami-nation requires the use of a

nasal speculum.

Nose and Sinuses

The

nurse inspects the external nose for lesions, asymmetry, or inflammation and

then asks the patient to tilt the head backward. Gently pushing the tip of the

nose upward, the nurse examines the internal structures of the nose, inspecting

the mucosa for color, swelling, exudate, or bleeding. The nasal mucosa is

nor-mally redder than the oral mucosa, but it may appear swollen and hyperemic

if the patient has a common cold. In allergic rhinitis, however, the mucosa

appears pale and swollen.

Next

the nurse inspects the septum for deviation, perforation, or bleeding. Most

people have a slight degree of septal deviation, but actual displacement of the

cartilage into either the right or left side of the nose may produce nasal

obstruction. Such deviation usually causes no symptoms.

While

the head is still tilted back, the nurse inspects the infe-rior and middle

turbinates. In chronic rhinitis, nasal polyps may develop between the inferior and

middle turbinates; they are dis-tinguished by their gray appearance. Unlike the

turbinates, they are gelatinous and freely movable.

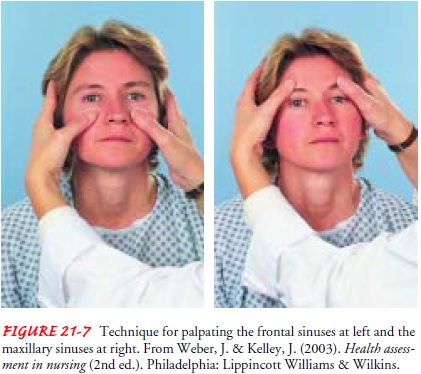

Next

the nurse may palpate the frontal and maxillary sinuses for tenderness (Fig.

21-7). Using the thumbs, the nurse applies gentle pressure in an upward fashion

at the supraorbital ridges (frontal sinuses) and in the cheek area adjacent to

the nose (max-illary sinuses). Tenderness in either area suggests inflammation.

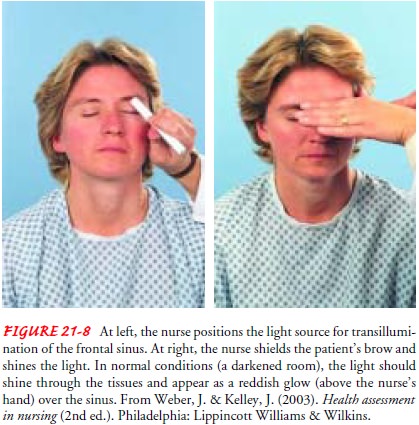

The frontal and maxillary sinuses can be inspected by transillu-mination

(passing a strong light through a bony area, such as the sinuses, to inspect

the cavity; Fig. 21-8). If the light fails to pen-etrate, the cavity is likely

to contain fluid or pus.

Pharynx and Mouth

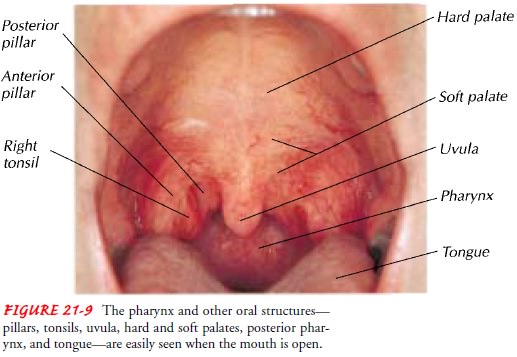

After

the nasal inspection, the nurse may assess the mouth and pharynx, instructing

the patient to open the mouth wide and take a deep breath. Usually this will

flatten the posterior tongue and briefly allow a full view of the anterior and

posterior pillars, ton-sils, uvula, and posterior pharynx (Fig. 21-9). The

nurse inspects these structures for color, symmetry, and evidence of exudate,

ul-ceration, or enlargement. If a tongue blade is needed to depress the tongue

to visualize the pharynx, it is pressed firmly beyond the midpoint of the tongue

to avoid a gagging response.

Trachea

Next

the position and mobility of the trachea are usually noted by direct palpation.

This is performed by placing the thumb and index finger of one hand on either

side of the trachea just above the sternal notch. The trachea is highly

sensitive, and palpating too firmly may trigger a coughing or gagging response.

The tra-chea is normally in the midline as it enters the thoracic inlet be-hind

the sternum, but it may be deviated by masses in the neck or mediastinum.

Pleural or pulmonary disorders, such as a pneu-mothorax, may also displace the

trachea.

Related Topics