Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment of Respiratory Function

Health History - Assessment of Respiratory Function

Assessment

HEALTH HISTORY

The health history focuses on the physical

and functional prob-lems of the patient and the effect of these problems on his

or her life. The reason the patient is seeking health care often is related to

one of the following: dyspnea

(shortness of breath), pain, ac-cumulation of mucus, wheezing, hemoptysis (blood spit up from the

respiratory tract), edema of the ankles and feet, cough, and general fatigue

and weakness.

In

addition to identifying the chief reason why the patient is seeking health

care, the nurse tries to determine when the health problem or symptom started,

how long it lasted, if it was relieved at any time, and how relief was

obtained. The nurse collects in-formation about precipitating factors,

duration, severity, and as-sociated factors or symptoms and also assesses for

risk factors and genetic factors that may contribute to the patient’s lung

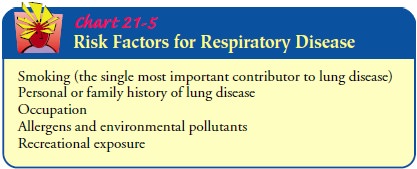

condi-tion (Chart 21-5).

The nurse assesses the impact of signs

and symptoms on the patient’s ability to perform activities of daily living and

to partic-ipate in usual work and family activities. In addition, psychoso-cial

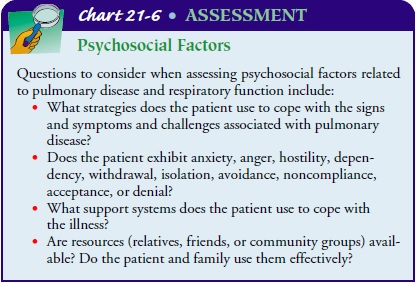

factors that may affect the patient are explored (Chart 21-6). These factors

include anxiety, role changes, family relationships, financial problems,

employment status, and the strategies the pa-tient uses to cope with them.

Many

respiratory diseases are chronic and progressively debil-itating. Therefore,

ongoing assessment of the patient’s physical abilities, psychosocial supports,

and quality of life is needed to plan appropriate interventions. It is

important for the patient with a respiratory disorder to understand the

condition and to be familiar with necessary self-care interventions. The nurse

evalu-ates these factors over time and provides education as needed.

Signs and Symptoms

The

major signs and symptoms of respiratory disease are dyspnea, cough, sputum

production, chest pain, wheezing, clubbing of the fingers, hemoptysis, and

cyanosis. These clinical manifestations are related to the duration and

severity of the disease.

DYSPNEA

Dyspnea (difficult or labored breathing, shortness of breath) is a symptom common to many pulmonary and cardiac disorders, particularly when there is decreased lung compliance or increased airway resistance. The right ventricle of the heart will be affected ultimately by lung disease because it must pump blood through the lungs against greater resistance. It may also be associated with neurologic or neuromuscular disorders such as myasthenia gravis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, or muscular dystrophy.

Clinical Significance.

In general, acute diseases of the lungs

pro-duce a more severe grade of dyspnea than do chronic diseases. Sudden

dyspnea in a healthy person may indicate pneumothorax (air in the pleural

cavity), acute respiratory obstruction, or ARDS. In immobilized patients,

sudden dyspnea may denote pulmonary embolism. Orthopnea (inability to breathe easily except in an upright

position) may be found in patients with heart disease and occasionally in

patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary dis-ease (COPD); dyspnea with an

expiratory wheeze occurs with COPD. Noisy breathing may result from a narrowing

of the air-way or localized obstruction of a major bronchus by a tumor or

foreign body. The presence of both inspiratory and expiratory wheezing usually

signifies asthma if the patient does not have heart failure.

The

circumstance that produces the dyspnea must be deter-mined. Therefore, it is

important to ask the patient the following questions:

·

How much exertion triggers shortness

of breath?

·

Is there an associated cough?

·

Is dyspnea related to other

symptoms?

·

Was the onset of shortness of breath

sudden or gradual?

·

At what time of day or night does

the dyspnea occur?

·

Is the shortness of breath worse

when the patient is flat in bed?

·

Does the shortness of breath occur

at rest? With exercise? Running? Climbing stairs?

· Is the shortness of breath worse while walking? If so, when walking how far? How fast?

Relief Measures.

The

management of dyspnea is aimed at iden-tifying and correcting its cause. Relief

of the symptom sometimes is achieved by placing the patient at rest with the

head elevated (high Fowler’s position) and, in severe cases, by administering

oxygen.

COUGH

Cough

results from irritation of the mucous membranes any-where in the respiratory

tract. The stimulus producing a cough may arise from an infectious process or

from an airborne irritant, such as smoke, smog, dust, or a gas. The cough is

the patient’s chief protection against the accumulation of secretions in the

bronchi and bronchioles.

Clinical Significance.

Cough may indicate serious pulmonarydisease. The nurse needs to evaluate the character of the cough— is it dry, hacking, brassy, wheezing, loose, or severe? A dry, irrita-tive cough is characteristic of an upper respiratory tract infection of viral origin or may be a side effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor therapy. Laryngotracheitis causes an ir-ritative, high-pitched cough. Tracheal lesions produce a brassy cough. A severe or changing cough may indicate bronchogenic carcinoma. Pleuritic chest pain accompanying coughing may in-dicate pleural or chest wall (musculoskeletal) involvement.

The time of coughing is also noted.

Coughing at night may herald the onset of left-sided heart failure or bronchial

asthma. A cough in the morning with sputum production may indicate bronchitis.

A cough that worsens when the patient is supine sug-gests postnasal drip

(sinusitis). Coughing after food intake may indicate aspiration of material

into the tracheobronchial tree. A cough of recent onset is usually from an

acute infection.

SPUTUM PRODUCTION

A patient who coughs long enough almost invariably produces sputum. Violent coughing causes bronchial spasm, obstruction, and further irritation of the bronchi and may result in syncope (fainting). A severe, repeated, or uncontrolled cough that is non-productive is exhausting and potentially harmful. Sputum production is the reaction of the lungs to any constantly recurring irritant. It also may be associated with a nasal discharge.

Clinical Significance.

A profuse amount of purulent sputum(thick and yellow, green, or rust-colored) or a change in color of the sputum probably indicates a bacterial infection. Thin, mu-coid sputum frequently results from viral bronchitis. A gradual increase of sputum over time may indicate the presence of chronic bronchitis or bronchiectasis. Pink-tinged mucoid sputum suggests a lung tumor. Profuse, frothy, pink material, often welling up into the throat, may indicate pulmonary edema. Foul-smelling sputum and bad breath point to the presence of a lung abscess, bronchiectasis, or an infection caused by fusospirochetal or other anaerobic organisms.

Relief Measures.

If

the sputum is too thick for the patient to ex-pectorate, it is necessary to

decrease its viscosity by increasing its water content through adequate

hydration (drinking water) and inhalation of aerosolized solutions, which may

be delivered by any type of nebulizer. Strategies to assist the patient to

cough pro-ductively are discussed later.

Smoking

is contraindicated with excessive sputum production because it interferes with

ciliary action, increases bronchial secre-tions, causes inflammation and

hyperplasia of the mucous mem-branes, and reduces production of surfactant.

Thus, smoking impairs bronchial drainage. When the person stops smoking, sputum

volume decreases and resistance to bronchial infections increases.

The

patient’s appetite may decrease because of the odor of the sputum or the taste

it leaves in the mouth. The nurse encourages adequate oral hygiene and wise

selection of food, measures that will stimulate appetite. In addition, the nurse

encourages the pa-tient and family to remove sputum cups, emesis basins, and

soiled tissues before mealtime. Encouraging the patient to drink citrus juices

at the beginning of the meal may increase the palatability of the rest of the

meal because these juices cleanse the palate of the sputum taste.

CHEST PAIN

Chest

pain or discomfort may be associated with pulmonary or car-diac disease. Chest

pain associated with pulmonary conditions may be sharp, stabbing, and

intermittent, or it may be dull, aching, and persistent. The pain usually is

felt on the side where the pathologic process is located, but it may be

referred elsewhere—for example, to the neck, back, or abdomen.

Clinical Significance.

Chest pain may occur with pneumonia,pulmonary embolism with lung

infarction, and pleurisy. It also may be a late symptom of bronchogenic

carcinoma. In carcinoma the pain may be dull and persistent because the cancer

has in-vaded the chest wall, mediastinum, or spine.

Lung

disease does not always produce thoracic pain because the lungs and the

visceral pleura lack sensory nerves and are in-sensitive to pain stimuli.

However, the parietal pleura has a rich supply of sensory nerves that are

stimulated by inflammation and stretching of the membrane. Pleuritic pain from irritation

of the parietal pleura is sharp and seems to “catch” on inspiration; pa-tients

often describe it as “like the stabbing of a knife.” Patients are more

comfortable when they lie on the affected side as this splints the chest wall,

limits expansion and contraction of the lung, and reduces the friction between

the injured or diseased pleurae on that side. Pain associated with cough may be

reduced manually by splinting the rib cage.

The

nurse assesses the quality, intensity, and radiation of pain and identifies and

explores precipitating factors, along with their relationship to the patient’s

position. Also, it is important to as-sess the relationship of pain to the

inspiratory and expiratory phases of respiration.

Relief Measures.

Analgesic

medications may be effective in re-lieving chest pain, but care must be taken

not to depress the respiratory center or a productive cough, if present.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) achieve this goal and thus are

used for pleuritic pain. A regional anesthetic block may be per-formed to

relieve extreme pain.

WHEEZING

Wheezing

is often the major finding in a patient with bron-choconstriction or airway

narrowing. It is heard with or without a stethoscope, depending on its

location. Wheezing is a high-pitched, musical sound heard mainly on expiration.

Relief Measures. Oral

or inhalant bronchodilator medicationsreverse wheezing in most instances.

CLUBBING OF THE FINGERS

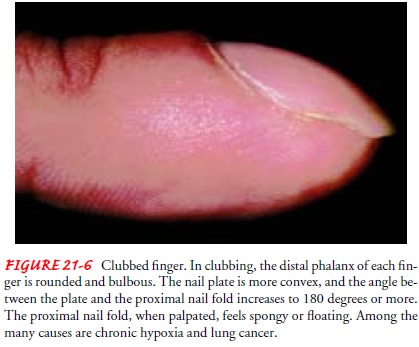

Clubbing

of the fingers is a sign of lung disease found in patients with chronic hypoxic

conditions, chronic lung infections, and ma-lignancies of the lung. This

finding may be manifested initially as sponginess of the nailbed and loss of

the nailbed angle (Fig. 21-6).

HEMOPTYSIS

Hemoptysis (expectoration of blood from the respiratory tract) is a symptom of both pulmonary and cardiac disorders. The onset of hemoptysis is usually sudden, and it may be intermittent or continuous. Signs, which vary from blood-stained sputum to a large, sudden hemorrhage, always merit investigation. The most common causes are:

·

Pulmonary infection

·

Carcinoma of the lung

·

Abnormalities of the heart or blood

vessels

·

Pulmonary artery or vein

abnormalities

·

Pulmonary emboli and infarction

Diagnostic

evaluation to determine the cause includes several studies: chest x-ray, chest

angiography, and bronchoscopy. A care-ful history and physical examination are

necessary to diagnose the underlying disease, irrespective of whether the

bleeding involved a very small amount of blood in the sputum or a massive

hemor-rhage. The amount of blood produced is not always proportional to the

seriousness of the cause.

First,

it is important to determine the source of the bleeding— the gums, nasopharynx,

lungs, or stomach. The nurse may be the only witness to the episode. When

documenting the bleeding episode, the nurse considers the following points:

·

Bloody sputum from the nose or the

nasopharynx is usually preceded by considerable sniffing, with blood possibly

ap-pearing in the nose.

·

Blood from the lung is usually

bright red, frothy, and mixed with sputum. Initial symptoms include a tickling

sensation in the throat, a salty taste, a burning or bubbling sensation in the

chest, and perhaps chest pain, in which case the pa-tient tends to splint the bleeding

side. The term “hemop-tysis” is reserved for the coughing up of blood arising

from a pulmonary hemorrhage. This blood has an alkaline pH (greater than 7.0).

·

If the hemorrhage is in the stomach,

the blood is vomited (hematemesis) rather than coughed up. Blood that has been

in contact with gastric juice is sometimes so dark that it is referred to as

“coffee grounds.” This blood has an acid pH (less than 7.0).

CYANOSIS

Cyanosis,

a bluish coloring of the skin, is a very late indicator of hypoxia. The

presence or absence of cyanosis is determined by the amount of unoxygenated

hemoglobin in the blood. Cyanosis ap-pears when there is 5 g/dL of unoxygenated

hemoglobin. A pa-tient with a hemoglobin level of 15 g/dL will not demonstrate

cyanosis until 5 g/dL of that hemoglobin becomes unoxygenated, reducing the

effective circulating hemoglobin to two thirds of the normal level. An anemic

patient rarely manifests cyanosis, and a polycythemic patient may appear

cyanotic even if adequately oxygenated. Therefore, cyanosis is not a reliable sign of hypoxia.

Assessment

of cyanosis is affected by room lighting, the pa-tient’s skin color, and the

distance of the blood vessels from the surface of the skin. In the presence of

a pulmonary condition, central cyanosis is assessed by observing the color of

the tongue and lips. This indicates a decrease in oxygen tension in the blood.

Peripheral cyanosis results from decreased blood flow to a certain area of the

body, as in vasoconstriction of the nailbeds or earlobes from exposure to cold,

and does not necessarily indicate a central systemic problem.

Related Topics