Definition, Merits, Demerits, Features - Parliamentary form of government | 11th Political Science : Chapter 6 : Forms of Government

Chapter: 11th Political Science : Chapter 6 : Forms of Government

Parliamentary form of government

Parliamentary form of government

Modern democratic governments are classified into

parliamentary and presidential on the basis of nature of relations between the

executive and the legislative organs of the government.

The parliamentary system of government is the one

in which the executive is responsible to the legislature for its policies and

acts. The presidential system of government, on the other hand, is one in which

the executive is not responsible to the legislature for its policies and acts,

and is constitutionally independent of the legislature in respect of its term

of office.

The parliamentary government is also known as

cabinet government irresponsible government or Westminster model of government

and is prevalent in Britain, Japan, Canada, India among others.

Ivor Jennings called

the

parliamentary system as ‘cabinet system’ because the cabinet is the

nucleus of power in a parliamentary system. The parliamentary government is

also known as ‘responsible government’ as the cabinet (the real executive) is

accountable to the Parliament and stays in office so long as it enjoys the

latter’s confidence.

It is described as ‘Westminster mod-el of

government’ after the location of the British Parliament, where the

parliamenta-ry system originated. In the past, the Brit-ish constitutional and

political experts de-scribed the Prime Minister as ‘primus inter pares’ (first

among equals) in relation to the cabinet. In the recent period, the Prime

Minister’s power, influence and position have increased significantly vis-a-vis

the cabinet. He has come to play a ‘dominant’ role in the British

politico-administrative system.

Features of parliamentary form of government

Nominal and Real Executives: The President is the nominal executive (de

jure executive or titular executive) while the Prime Minister is the real

executive (de facto executive). Thus, the President is head of the State, while

the Prime Minister is head of the government.

Majority Party Rule: The political party which secures majority seats in the

LokSabha forms the government. The leader of that party is appointed

as the Prime Minister by the President; other ministers are appointed by the

President on the advice of the prime minister. However, when no single party

gets the majority, a coalition of parties may be invited by the President to

form the government.

Collective Responsibility: This is the bedrock principle of parliamentary

government. The ministers are collectively responsible to the Parliament.

Double Membership: The ministers are members of both the legislature and the executive.

Leadership of the Prime Minister: The Prime Minister plays the leadership

role in this system of government. He is the leader of council of ministers,

leader of the Parliament and leader of the party in power. In these capacities,

he plays a significant and highly crucial role in the functioning of the

government.

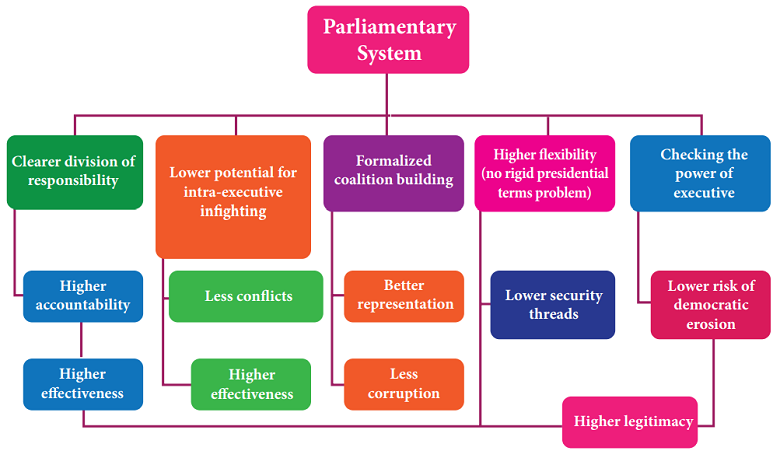

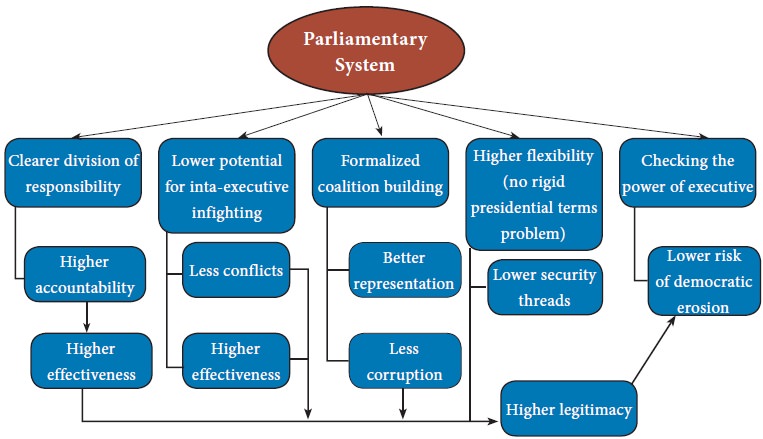

Merits of the parliamentary form of government

Harmony between Legislature and Executive: The greatest advantage of the parliamentary system

is that it ensures harmonious relationship and cooperation between the

egislative and executive organs of the government. The executive is a part of

the legislature and both are inter dependent at work. As a result, there is

less scope for disputes and conflicts between the two organs.

Responsible Government: In the parliamentary system establishes a

responsible government. The ministers are responsible to the Parliament for all

their acts of omission and commission. The Parliament exercises control

over the ministers through various devices like question hour, discussions,

adjournment motion, no confidence motion, etc.

Prevents Despotism: under this system, the executive authority is vested in a

group of individuals (council of ministers) and not in a single person. This

dispersal of authority checks the dictatorial tendencies of the executive.

Moreover, the executive is responsible to the Parliament and can be removed by

a no-confidence motion.

Wide Representation: In a parliamentary system, it is possible to provide

representation to all sections and regions in the government. The prime

minister while selecting his minister scan take this factor into consideration.

Demerits of the parliamentary form of government

Unstable Government: The parliamentary system does not provide a stable

government. There is no guarantee that a government can survive its tenure. The

ministers depend on the majority legislators for their continuity and survival

in office.

ii. no-confidence

motion or political defection or evils of multiparty coalition can make the

government unstable.

No Continuity of Policies: The parliamentary system is not conductive

for the formulation and implementation of long-term policies. This is due to

the uncertainty of the tenure of the government. A change in the ruling party

is usually followed by changes in the policies of the government.

Dictatorship of the Cabinet: When the ruling party enjoys absolute majority

in the Parliament, the cabinet becomes autocratic and exercises nearly

unlimited powers.

Harold J Laski says that

the

parliamentary system gives the executive an opportunity for tyranny.

Ramsay Muir, the

former British Prime Minister, also complained of the ‘dictatorship of the

cabinet’.

Against Separation of Powers: In the parliamentary system, the legislature and the executive are together and inseparable. The cabinet acts as the leader of legislature as well as the executive. Hence, the whole system of government goes against the letter and spirit of the theory of separation of powers.

Raju Ramachandran , senior advocate at the Supreme Court of India

This debate is academic. A switchover to the

presidential system is not possible under our present constitutional scheme

because of the ‘basic structure’ doctrine propounded by the Supreme Court in

1973 which has been accepted by the political class without reservation, except

for an abortive attempt during the Emergency by Indira Gandhi’s government to

have it overturned. The Constituent Assembly had made an informed choice after

considering both the British model and the American model and after Dr. B.R.

Ambedkar had drawn up a balance sheet of their merits and demerits. To alter

the informed choice made by the Constituent Assembly would violate the ‘basic

structure’ of the Constitution. I must clarify that I have been a critic of the

‘basic structure’ doctrine.

Abuse of power worries

A presidential system centralises power in one

individual unlike the parliamentary system, where the Prime Minister is the

first among equals. The surrender to the authority of one individual, as in the

presidential system, is dangerous for democracy. The over-centralisation of

power in one individual is something we have to guard against. Those who argue

in favour of a presidential system often state that the safeguards and checks

are in place: that a powerful President can be stalled by a powerful

legislature. But if the legislature is dominated by the same party to which the

President belongs, a charismatic President or a “strong President” may prevent

any move from the legislature. On the other hand, if the legislature is

dominated by a party opposed to the President’s party and decides to checkmate

him, it could lead to a stalemate in governance because both the President and

the legislature would have democratic legitimacy.

A diverse country like India cannot function

without consensus-building. This “winner takes it all” approach, which is a

necessary consequence of the presidential system, is likely to lead to a

situation where the views of an individual can ride roughshod over the

interests of different segments.

What about the States?

The other argument, that it is easier to bring

talent to governance in a presidential system, is specious. You can get

‘outside’ talent in a parliamentary system too. Right from C.D. Deshmukh, T.A.

Pai, Manmohan Singh, M.G.K. Menon and Raja Ramanna talent has been coming into

the parliamentary system with the added safeguard of democratic accountability,

because the ‘outsiders’ have to get elected after assuming office. On the other

hand, bringing ‘outside’ talent in a presidential system without people being democratically

elected would deter people from giving independent advice to the chief

executive because they owe their appointment to him/her.

Those who speak in favour of a presidential system

have only the Centre in mind. They have not thought of the logical consequence,

which is that we will have to move simultaneously to a “gubernatorial” form in

the States. A switch at the Centre will also require a change in the States.

Are we ready for that?

Changing

to a presidential system is the best way of ensuring a democracy that works

Our parliamentary system is a perversity only the

British could have devised: to vote for a legislature in order to form the

executive. It has created a unique breed of legislator, largely unqualified to

legislate, who has sought election only in order to wield executive power.

There is no genuine separation of powers: the legislature cannot truly hold the

executive accountable since the government wields the majority in the House.

The parliamentary system does not permit the existence of a legislature

distinct from the executive, applying its collective mind freely to the

nation’s laws.

For 25 years till 2014, our system has also

produced coalition governments which have been obliged to focus more on

politics than on policy or performance. It has forced governments to

concentrate less on governing than on staying in office, and obliged them to

cater to the lowest common denominator of their coalitions, since withdrawal of

support can bring governments down. The parliamentary system has distorted the

voting preferences of an electorate that knows which individuals it wants but

not necessarily which parties or policies.

Failures in the system

India’s many challenges require political

arrangements that permit decisive action, whereas ours increasingly promote

drift and indecision. We must have a system of government whose leaders can

focus on governance rather than on staying in power.

A system of directly elected chief executives at

all levels – panchayat chiefs, town mayors, Chief Ministers (or Governors) and

a national President – elected for a fixed term of office, invulnerable to the

whims of the legislature, and with clearly defined authority in their

respective domains – would permit India to deal more efficiently with its critical

economic and social challenges.

Cabinet posts would not be limited to those who are

electable rather than those who are able. At the end of a fixed period of time

— say the same five years we currently accord to our Lok Sabha

— the public would be able to judge the individual

on performance in improving the lives of Indians, rather than on political

skill at keeping a government in office.

The fear that an elected President could become a

Caesar is ill-founded since the President’s power would be balanced by directly

elected chief executives in the States. In any case, the Emergency demonstrated

that even a parliamentary system can be distorted to permit autocratic rule.

Dictatorship is not the result of a particular type of governmental system.

Direct accountability

Indeed, the President would have to work with

Parliament to get his budget through or to pass specific Bills. India’s

fragmented polity, with dozens of political parties in the fray, makes a

U.S.-style two-party gridlock in Parliament impossible. An Indian presidency,

instead of facing a monolithic opposition, would have the opportunity to build

issue-based coalitions on different issues, mobilising different temporary

alliances of different smaller parties from one policy to the next – the

opposite of the dictatorial steamroller some fear a presidential system could

produce.

Any politician with aspirations to rule India as

President will have to win the support of people beyond his or her home turf;

he or she will have to reach out to different groups, interests, and

minorities. And since the directly elected President will not have coalition

partners to blame for his or her inaction, a presidential term will have to be

justified in terms of results, and accountability will be direct and personal.

Democracy, as I have long argued, is vital for

India’s survival: we are right to be proud of it. But few Indians are proud of

the kind of politics our democracy has inflicted upon us. With the needs and

challenges of one-sixth of humanity before our leaders, we must have a

democracy that delivers progress to our people. Changing to a presidential

system is the best way of ensuring a democracy that works. It is time for a

change.

Upendra Baxi, legal scholar and the former vice-chancellor of Delhi University

I think the debate has a life cycle of its own. It

has been brought up and discussed whenever there has been a super-majority

government. From Jawaharlal Nehru to Indira Gandhi to the present, the

presidential system has been debated extensively around two aspects: is it

desirable, and second, is it feasible?

To tackle the second aspect first, unless the

Supreme Court changes its mind, any such amendment would violate the ‘basic

structure’ of the Constitution as was decided with, and since, the Kesavnanda

Bharthi case. There is no way to get around this unless the Supreme Court now

takes a wholly different view.

Different models

On the desirability aspect, which presidential

system are we talking about when we pit the American presidential system

against the Westminster model? In the American system, the President appoints

his officers; they have limited tenure and their offices are confirmed by the

Senate (Upper House). Then, we have the Latin American model, where some

Constitutions give Presidents a term often amounting to a life tenure like in

Cuba. There are plenty of models to choose from and there are arguments against

each. So, which system is being argued for when the votaries of change seek a

shift to the presidential system?

Our Rajya Sabha cannot be compared to the U.S.

Senate where each state has its own Constitution and has the power to change

it. The relationship between the states and the federal government is

extraordinary; as is the status of their courts and the manner of appointment

of judges. I do not think people have thought about it. Merely stating that a

change to the presidential system is needed does not mean much. The Indian

debate currently is not focussed on the kind of presidential system envisaged.

What is the term we are seeking for the President? Should he/ she be

re-elected? If so, for how many terms? Then, who decides the change? Parliament?

All this requires a massive amendment to the ‘basic structure’ of the

Constitution. The Supreme Court has spelt its view on the ‘basic structure’ of

the Constitution.

Giving an opinion is one thing. A judgment is a

more carefully considered conclusion. Those who support the presidential system

should do their homework when they argue against the parliamentary system.

There is also the matter of separation of powers. In the U.S., the President,

who is also the Supreme Commander, has the power to veto the Congress. Does

India need this? The manner of removing the U.S. President through impeachment

is a very complex process. There is also the possibility of aggregating more

powers to the President.

One could argue that the parliamentary system too

runs a similar risk. I do not think it has been thought over. It is not on the

table yet.

Reform the process

On the other hand, there are ideas going around

about reforming the electoral processes to make democracy more robust. From

limiting expenditure of political parties and deciding the ceiling on the

expenditure, to holding simultaneous elections, declaring the results for a combination

of booths instead of constituencies — I think it is advisable to debate this

and ensure that the gaping loopholes in the electoral processes are speedily

plugged.

The present parliamentary system has been tried and

tested for nearly 70 years. Rather than change the system, why not reform

thoroughly and cleanse the electoral processes?

Why the framers of the Indian Constitution adopted for the Parliamentary Form of Government?

iii.

Familiarity with the System

iv.

Preference to More Responsibility

v.

Need to Avoid

Legislative—Executive Conflicts

vi.

Nature of Indian Society, India

is one of the most heterogeneous States and most complex plural societies in

the world. Hence, the Constitution-makers adopted the parliamentary system as

it offers greater scope for giving representation to various section, interests

and regions in the government. This promotes a national spirit among the people

and builds audited India.

Related Topics