Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Oncologic or Degenerative Neurologic Disorders

ParkinsonŌĆÖs Disease

PARKINSONŌĆÖS DISEASE

ParkinsonŌĆÖs disease is a

slowly progressing neurologic movement disorder that eventually leads to

disability. The degenerative or id-iopathic form is the most common; there is

also a secondary form with a known or suspected cause. Although the cause of

most cases is unknown, research suggests several causative factors, including

ge-netics, atherosclerosis, excessive accumulation of oxygen free radi-cals,

viral infections, head trauma, chronic antipsychotic medication use, and some

environmental exposures. Parkinsonian symptoms usually first appear in the

fifth decade of life; however, cases have been diagnosed at the age of 30

years. It is the fourth most common neurodegenerative

disease. ParkinsonŌĆÖs disease affects men morefrequently than women and

nearly 1% of the population older than 60 years of age (Gray & Hildebrand,

2000).

Pathophysiology

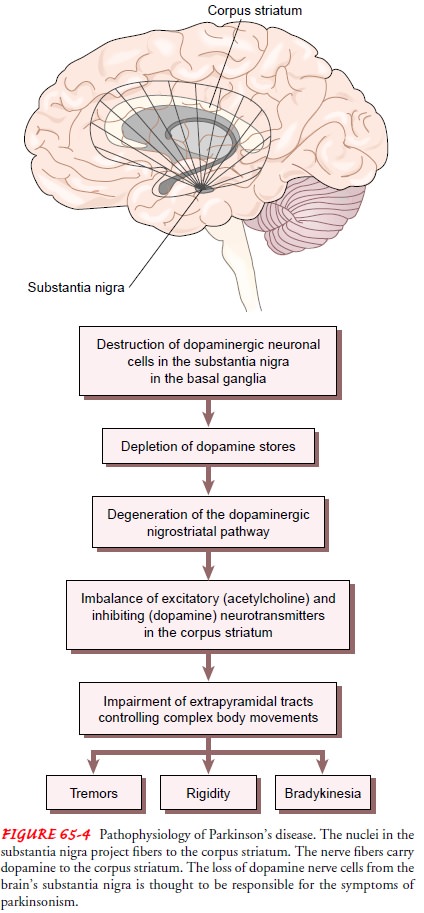

ParkinsonŌĆÖs disease is associated with decreased levels of dopamine due to destruction of pigmented neuronal cells in the substantia nigra in the basal ganglia of the brain (Fig. 65-4). The nuclei of the substantia nigra project fibers or neuronal pathways to the corpus striatum, where neurotransmitters are key to control of complex body movements.

Through the

neurotransmitters acetyl-choline (excitatory) and dopamine (inhibitory),

striatal neurons relay messages to the higher motor centers that control and

refine motor movements. The loss of dopamine stores in this area of the brain

results in more excitatory neurotransmitters than inhibitory neurotransmitters,

leading to an imbalance that affects voluntary movement.

Basic science research in the past two decades has

revealed that more neurotransmitter pathways in the brain than just the

dopaminergic system are involved. Parts of the glutamatergic, cholinergic,

tryptaminergic, noradrenergic, adrenergic, seroton-ergic, and peptidergic

pathways (responsible for cell metabolism, growth, nutrition, and so forth)

show damage in ParkinsonŌĆÖs dis-ease (Chase, Oh & Konitsiotis, 2000;

Przuntek, 2000; Rascol, 2000).

Clinical symptoms do not appear until 60% of the

pigmented neurons are lost and the striatal dopamine level is decreased by 80%.

Cellular degeneration impairs the extrapyramidal tracts that control

semiautomatic functions and coordinated movements; motor cells of the motor cortex

and the pyramidal tracts are not affected.

Clinical Manifestations

ParkinsonŌĆÖs disease has

a gradual onset and symptoms progress slowly over a chronic, prolonged course.

The three cardinal signs are tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia (abnormally slow move-ments). Other features include

hypokinesia, gait disturbances, and postural instability (Gray &

Hildebrand, 2000).

TREMOR

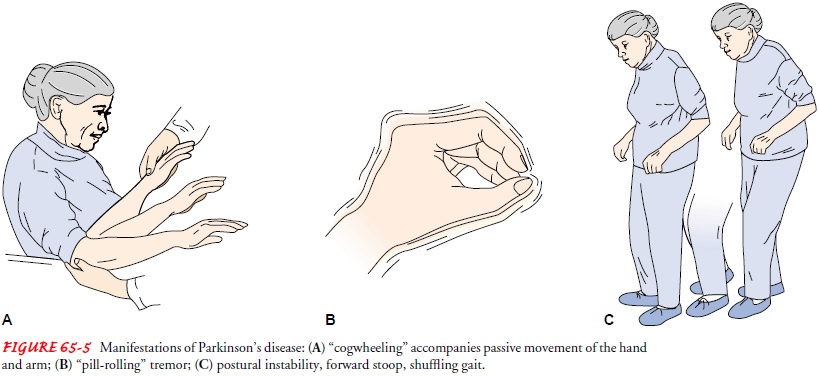

Although symptoms are

variable, a slow, unilateral, resting tremor is present in 70% of patients at

the time of diagnosis. Resting tremor characteristically disappears with

purposeful movement but is evident when the extremities are motionless. The

tremor may present as a rhythmic, slow turning motion (pronationŌĆō supination)

of the forearm and the hand and a motion of the thumb against the fingers as if

rolling a pill (Fig. 65-5). Tremor is present while the patient is at rest; it

increases when the patient is walking, concentrating, or feeling anxious.

RIGIDITY

Resistance to passive

limb movement characterizes muscle rigidity. Passive movement of an extremity

may cause the limb to move in jerky increments referred to as cogwheeling.

Rigidity of the pas-sive extremity increases when another extremity is engaged

in voluntary active movement. Stiffness of the neck, trunk, and shoul-ders is

common. Early in the disease, the patient may complain of shoulder pain.

BRADYKINESIA

One of the most common features of ParkinsonŌĆÖs disease is

brady-kinesia. Patients take longer to complete most activities and have

difficulty initiating movement, such as rising from a sitting posi-tion or

turning in bed.

Hypokinesia (abnormally

diminished movement) is also com-mon and may appear after the tremor. The

freezing phenomenon is a transient inability to perform active movement and is

thought to be an extreme form of bradykinesia. Additionally, the patient tends

to shuffle and exhibits a decreased arm swing. As dexterity declines, micrographia (shrinking, slow

handwriting) develops. The face becomes increasingly masklike and

expressionless and the frequency of blinking decreases. Dysphonia (soft, slurred, low-pitched, and less audible speech) may

occur due to weakness and incoordination of the muscles responsible for speech.

In many cases, the patient develops dysphagia, begins to drool, and is at risk

for choking and aspiration.

The patient commonly develops postural and gait problems. There is a loss of postural reflexes, and the patient stands with the head bent forward and walks with a propulsive gait. The posture is caused by the forward flexion of the neck, hips, knees, and el-bows. The patient may walk faster and faster, trying to move the feet forward under the bodyŌĆÖs center of gravity (shuffling gait). Difficulty in pivoting and loss of balance (either forward or back-ward) places the patient at risk for falls.

OTHER MANIFESTATIONS

The effect of ParkinsonŌĆÖs disease on the basal ganglia

often pro-duces autonomic symptoms that include excessive and un-controlled

sweating, paroxysmal flushing, orthostatic hypotension, gastric and urinary

retention, constipation, and sexual distur-bances (Herndon et al., 2000).

Psychiatric changes are

often interrelated and may be predictive of one another. They include

depression, dementia (progressive

mental deterioration), sleep disturbances, and hallucinations (Herndon et al.,

2000). Depression is common; whether it is a reaction to the disorder or is

related to a biochemical abnormal-ity remains a question. Mental changes may

appear in the form of cognitive, perceptual, and memory deficits, although

intellect is not usually affected. A number of psychiatric manifestations

(personality changes, psychosis, dementia, and acute confusion) are common

among the elderly. The prevalence of dementia is about 25% and the pattern is

similar to that of patients with AlzheimerŌĆÖs disease. Although there is no

direct documented causal relationship, the rates of depression and dementia are

highly cor-related in these patients (Herndon et al., 2000).Approximately 41%

of women and 25% of men with Parkin-sonŌĆÖs disease experience sleep

disturbances. This may be connected to depression, dementia, or medications.

Auditory and visual hal-lucinations have been reported in approximately 37% of

persons with ParkinsonŌĆÖs and may be associated with depression, demen-tia, lack

of sleep, or adverse effects of medications (Herndon et al., 2000).

Complications associated

with ParkinsonŌĆÖs disease are com-mon and are typically related to disorders of

movement. As the disease progresses, patients are at risk for respiratory and

urinary tract infection, skin breakdown, and injury from falls. The ad-verse

effects of medications used to treat the symptoms are asso-ciated with numerous

complications.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Laboratory tests and imaging studies are not helpful in

the diag-nosis of ParkinsonŌĆÖs disease, although PET scanning has been used in

evaluating levodopa (precursor of dopamine) uptake and conversion to dopamine

in the corpus striatum (Freed et al., 2001). Currently, the disease is

diagnosed clinically from the pa-tientŌĆÖs history and the presence of two of the

three cardinal man-ifestations: tremor, muscle rigidity, and bradykinesia.

Early diagnosis can be

difficult because the patient can rarely pinpoint when symptoms started. Often

a family member notices a change such as stooped posture, a stiff arm, a slight

limp, tremor, or slow, small handwriting. The medical history, presenting

symp-toms, neurologic examination, and response to pharmacologic management are

carefully evaluated when making the diagnosis.

Medical Management

Treatment is directed at

controlling symptoms and maintaining functional independence because there are

no medical or surgical approaches that prevent disease progression. Care is

individual-ized for each patient based on presenting symptoms and social,

occupational, and emotional needs. Pharmacologic management is the mainstay of

treatment, although advances in research have led to increased interest in

surgical interventions. Patients are usu-ally cared for at home and admitted to

the hospital only for com-plications or to initiate new treatments.

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Antiparkinsonian

medications act by 1) increasing striatal dopa-minergic activity, 2) reducing

the excessive influence of excitatory cholinergic neurons on the extrapyramidal

tract, thereby restor-ing a balance between dopaminergic and cholinergic

activities, oracting on neurotransmitter pathways other than the dopami-nergic

pathway.

Antiparkinsonian Medications.

Levodopa (Dopar,

Larodopa) isthe most effective agent and the mainstay of treatment (Karch,

2002; Obeso et al., 2001). Because levodopa is thought to pre-cipitate

oxidation, which further damages the substantia nigra and eventually speeds

disease progression, physicians delay pre-scribing the medication or increasing

the dosage for as long as possible (Karch, 2002). Levodopa is converted to

dopamine in the basal ganglia, producing symptom relief. The beneficial

ef-fects of levodopa are most pronounced in the first few years of treatment.

Benefits begin to wane and adverse effects become more severe over time.

Confusion, hallucinations, depression, and sleep alterations are associated

with prolonged use. Levodopa is usually given in combination with carbidopa

(Sinemet), an amino acid decarboxylase

inhibitor that helps to maximize the beneficial effects of levodopa by

preventing its breakdown out-side the brain and reducing its adverse effects

(Karch, 2002).

Within 5 to 10 years, most patients develop a response to

the medication characterized by dyskinesia

(abnormal involun-tary movements), including facial grimacing, rhythmic jerking

movements of the hands, head bobbing, chewing and smacking movements, and

involuntary movements of the trunk and extrem-ities. The patient may experience

an onŌĆōoff syndrome in which sudden periods of near immobility (ŌĆ£off effectŌĆØ)

are followed by a sudden return of effectiveness (ŌĆ£on effectŌĆØ). Various

adjunctive therapies are used to minimize dyskinesias (Przuntek, 2000; Rascol,

2000).

Budipine, available in

Europe but not the United States, is a non-dopaminergic, antiparkinsonian

medication that significantly reduces akinesia, rigidity, and tremor. It is

non-dopaminergic be-cause the action appears to be on neurotransmitter pathways

other than the dopaminergic pathway. It may be used as monotherapy or in

conjunction with other available antiparkinsonian medica-tions (Przuntek, 2000;

Przuntek et al., 2002). The usual dose of 40 to 60 mg is reached gradually.

Nausea and dry mouth are the most common side effects, although 75% of patients

experienced no side effects in clinical drug trials (Przuntek, 2000).

Anticholinergic Therapy.

Anticholinergic agents

(trihexyphenidyl,cycrimine, procyclidine, biperiden, and benztropine mesylate)

are effective in controlling tremor and rigidity. They may be used in

combination with levodopa. They counteract the action of the neurotransmitter

acetylcholine. Because the side effects include blurred vision, flushing, rash,

constipation, urinary retention, and acute confusional states, these

medications are often poorly tol-erated in elderly patients. Intraocular

pressure must be closely monitored: these medications are contraindicated in

patients with narrow-angle glaucoma. Patients with prostate hyperplasia are

monitored for signs of urinary retention.

Antiviral Therapy.

Amantadine hydrochloride

(Symmetrel) is anantiviral agent used in early ParkinsonŌĆÖs treatment to reduce

rigidity, tremor, and bradykinesia. It is thought to act by releasing dopamine

from neuronal storage sites. Studies suggest it may also have antiglutamatergic

properties that affect the glutamatergic pathway, thus improving

levodopa-induced dyskinesias (Rascol, 2000). Amantadine has a low incidence of

side effects, which in-clude psychiatric disturbances (mood changes, confusion,

depres-sion, hallucinations), lower extremity edema, nausea, epigastric

distress, urinary retention, headache, and visual impairment.

Dopamine Agonists.

Bromocriptine mesylate

and pergolide (ergotderivatives) are dopamine receptor agonists and are useful

in postponing the initiation of carbidopa or levodopa therapy. Dopamine

agonists are often added to the medication regimen when carbidopa or levodopa

loses effectiveness. Pergolide (Permax) is 10 times more potent than

bromocriptine mesylate (Parlodel), although this provides no therapeutic

advantage. Adverse re-actions to these medications include nausea, vomiting,

diar-rhea, lightheadedness, hypotension, impotence, and psychiatric effects.

Two new dopamine

agonists, ropinirole hydrochloride (Requip) and pramipexole (Mirapex) (nonergot

derivatives), are primarily for patients in the early stages of ParkinsonŌĆÖs

disease and are not expected to have the potentially serious adverse effects of

per-golide and bromocriptine mesylate. Pramipexole (Mirapex) canbe used without

levodopa for treatment of early disease and with levodopa in advanced stages.

Cabergoline (Dostinex), an ergot alkaloid with a long duration of action, has

been approved for use.

Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAO Inhibitors).

Of

the MAOinhibitors, selegiline (Eldepryl) is one of the most exciting and

controversial developments in the pharmacotherapy of Parkin-sonŌĆÖs disease

(Herndon et al., 2000). This medication inhibits dopamine breakdown and is

thought to slow the progression of the disease. Researchers believe this

medication may have a neuro-protective effect in the early stages of

ParkinsonŌĆÖs disease, but this has not been shown in clinical trials. Selegiline

is currently used in combination with a dopamine agonist to delay the use of

car-bidopa or levodopa therapy. Adverse effects are similar to those of

levodopa.

Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) Inhibitors.

Clinical trialssuggest

that the COMT inhibitors entacapone (Comtess) and tolcapone (Tasmar) have

little effect on parkinsonian symptoms when given alone but can increase the

duration of action of car-bidopa or levodopa when given in combination with

them. COMT inhibitors block an enzyme that metabolizes levodopa, making more

levodopa available for conversion to dopamine in the brain. Entacapone and

tolcapone reduce motor fluctuations in patients with advanced ParkinsonŌĆÖs

disease.

Antidepressants.

Tricyclic antidepressants may be prescribed

toalleviate the depression that is so common in ParkinsonŌĆÖs disease. The usual

dosage is one-third to one-half the dosage used in de-pressed patients without

ParkinsonŌĆÖs disease. Amitriptyline is typ-ically prescribed because of its

anticholinergic and antidepressant effect. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such

as fluoxetine hydro-chloride (Prozac) and bupropion hydrochloride (Wellbutrin),

are effective for treating depression but may aggravate parkinsonism.

Antihistamines.

Diphenhydramine hydrochloride

(Benadryl),orphenadrine citrate (Banflex), and phenindamine hydrochloride

(Neo-Synephrine) have mild central anticholinergic and sedative effects and may

reduce tremors.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The limitations of

levodopa therapy, improvements in stereotac-tic surgery, and new approaches in

transplantation have renewed interest in the surgical treatment of ParkinsonŌĆÖs

disease. In pa-tients with disabling tremor, rigidity, or severe

levodopa-induced dyskinesia, surgery may be considered. Although surgery

provides some relief in selected patients, it has not been shown to alter the

course of the disease or produce permanent improvement.

Stereotactic Procedures.

Thalamotomy and

pallidotomy areeffective in relieving many of the symptoms of ParkinsonŌĆÖs

dis-ease. Patients eligible for these procedures are those who have had an

inadequate response to medical therapy; they must meet strict criteria to be

eligible. Candidates eligible for these procedures are patients with idiopathic

ParkinsonŌĆÖs disease who are taking max-imum doses of antiparkinsonian

medications. Patients with de-mentia and atypical ParkinsonŌĆÖs disease are

usually not considered for stereotactic procedures. ParkinsonŌĆÖs disease rating

scales and specific neurologic testing are used to identify eligible

patients.The intent of thalamotomy and pallidotomy is to interrupt the nerve

pathways and thereby alleviate tremor or rigidity. During thalamotomy, a

stereotactic electrical stimulator destroys part of the ventrolateral portion

of the thalamus in an attempt to reduce tremor; the most common complications

are ataxia and hemiparesis. Pallidotomy involves destroying part of the ventral

aspect of the medial globus pallidus through electrical stimula-tion in

patients with advanced disease. The procedure is effective in reducing

rigidity, bradykinesia, and dyskinesia, thus improv-ing motor function and

activities of daily living in the immediate postoperative course. In small

studies, clinical improvements have been demonstrated over 3 to 4 years. The

clinical benefit is greater in patients younger than 60 years (Freed et al.,

2001). Complications include hemiparesis, stroke, and visual changes.

CT, x-rays, MRI, or angiography is used to localize the

ap-propriate surgical site in the brain. Then the patientŌĆÖs head is po-sitioned

in a stereotactic frame (Fig. 65-6). The surgeon makes an incision in the skin

and then a burr hole. Next, the surgeon passes an electrode through the burr

hole to the target area in the thalamus or globus pallidum. The desired

response of the patient to the electrical stimulation is the basis for the

final site chosen by the neurosurgeon. Stereotactic procedures are completed on

one side of the brain at a time. If rigidity or tremor is bilateral, a 6-month

interval is suggested between procedures.

Neural Transplantation.

Surgical implantation of adrenal medul-lary tissue

into the corpus striatum is performed in an effort to reestablish normal

dopamine release. Preliminary evidence has shown high morbidity and mortality

rates, and the implants ap-pear to improve parkinsonian symptoms for only 6

months. Re-searchers are conducting studies to determine if transplanting human

fetal brain cells or genetically engineered cells into the ni-grostriatal

region is effective (Aminoff, 2000). Legal and ethical issues surrounding the

use of fetal brain cells have limited the im-plementation of this procedure.

Recently, fetal pig neuronal cells survived transplantation into a patient with

ParkinsonŌĆÖs dis-ease; this may provide an alternative to human cell transplants

(Aminoff, 2000).

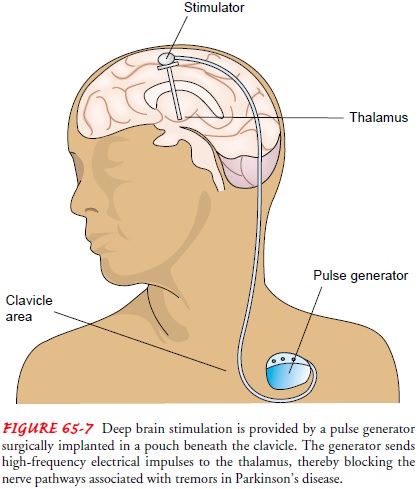

Deep Brain Stimulation.

Recently approved by the FDA,pacemaker-like brain implants show promising results in relieving tremors. The stimulation can be bilateral or unilateral, although bilateral stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus is thought to be of greater benefit to patients than results achieved with thala-motomy, pallidotomy, or fetal nigral transplantation (Obeso et al., 2001).

In deep brain stimulation, an electrode is placed in the thalamus and connected

to a pulse generator implanted in a subcutaneous subclavicular or abdominal

pouch. The battery-powered pulse generator sends high-frequency electrical

impulses through a wire placed under the skin to a lead anchored to the skull

(Fig. 65-7). The electrode blocks nerve pathways in the brain that cause

tremors. These devices are not without compli-cations, both from the surgical

procedure needed for implanta-tion and from complications (such as lead

leakage) of the device itself (Koller et al., 2001; Obeso et al., 2001).

Related Topics