Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Gastric and Duodenal Disorders

Nursing Process: The Patient With Ulcer Disease

NURSING

PROCESS:THE PATIENT WITH ULCER DISEASE

Assessment

The

nurse asks the patient to describe the pain and the methods used to relieve it

(e.g., food, antacids). The patient usually describes peptic ulcer pain as

burning or gnawing; it occurs about 2 hours after a meal and frequently awakens

the patient between midnight and 3 AM. Taking antacids,

eating, or vomiting often relieves the pain. If the patient reports a recent

history of vomiting, the nurse determines how often emesis has occurred and

notes important characteristics of the vomitus: Is it bright red, does it

resemble coffee grounds, or is there undigested food from previous meals? Has

the patient noted any bloody or tarry stools?

The

nurse also asks the patient to list his or her usual food in-take for a 72-hour

period and to describe food habits (e.g., speed of eating, regularity of meals,

preference for spicy foods, use of sea-sonings, use of caffeinated beverages

and decaffeinated coffee). Lifestyle and habits are a concern as well. Does the

patient use irri-tating substances? For example, does he or she smoke

cigarettes? If yes, how many? Does the patient ingest alcohol? If yes, how much

and how often? Are NSAIDs used? The nurse inquires about the patient’s level of

anxiety and his or her perception of current stres-sors. How does the patient

express anger or cope with stressful sit-uations? Is the patient experiencing

occupational stress or problems within the family? Is there a family history of

ulcer disease?

The

nurse assesses vital signs and reports tachycardia and hypotension, which may

indicate anemia from GI bleeding. The stool is tested for occult blood, and a

physical examination, in-cluding palpation of the abdomen for localized

tenderness, is per-formed as well.

Diagnosis

NURSING DIAGNOSES

Based

on the assessment data, the patient’s nursing diagnoses may include the

following:

•

Acute pain related to the effect of gastric acid

secretion on damaged tissue

•

Anxiety related to coping with an acute disease

•

Imbalanced nutrition related to changes in diet

•

Deficient knowledge about prevention of symptoms

and management of the condition

COLLABORATIVE PROBLEMS/POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS

Potential

complications may include the following:

•

Hemorrhage

•

Perforation

•

Penetration

•

Pyloric obstruction (gastric outlet obstruction)

Planning and Goals

The

goals for the patient may include relief of pain, reduced anx-iety, maintenance

of nutritional requirements, knowledge about the management and prevention of

ulcer recurrence, and absence of complications.

Nursing Interventions

RELIEVING PAIN

Pain

relief can be achieved with prescribed medications. The patient should avoid

aspirin, foods and beverages that contain caffeine, and decaffeinated coffee,

and meals should be eaten at regularly paced intervals in a relaxed setting.

Some patients benefit from learning relaxation techniques to help manage stress

and pain and to en-hance smoking cessation efforts.

REDUCING ANXIETY

The

nurse assesses the patient’s level of anxiety. Patients with pep-tic ulcers are

usually anxious, but their anxiety is not always obvi-ous. Appropriate

information is provided at the patient’s level of understanding, all questions

are answered, and the patient is en-couraged to express fears openly.

Explaining diagnostic tests and administering medications on schedule also help

to reduce anxi-ety. The nurse interacts with the patient in a relaxed manner,

helps identify stressors, and explains various coping techniques and relaxation

methods, such as biofeedback, hypnosis, or be-havior modification. The

patient’s family is also encouraged to participate in care and to provide

emotional support.

MAINTAINING OPTIMAL NUTRITIONAL STATUS

The

nurse assesses the patient for malnutrition and weight loss. After recovery

from an acute phase of peptic ulcer disease, the pa-tient is advised about the

importance of complying with the med-ication regimen and dietary restrictions.

MONITORING AND MANAGING POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS

Hemorrhage

Gastritis

and hemorrhage from peptic ulcer are the two most common causes of upper GI

tract bleeding. Hemorrhage, the most common complication, occurs in about 15%

of patients with peptic ulcers (Yamada, 1999). The site of bleeding is usually

the distal portion of the duodenum. Bleeding may be manifested by hematemesis

or melena (tarry stools). The vomited

blood can be bright red, or it can have a “coffee grounds” appearance (which is

dark) from the oxidation of hemoglobin to methemoglobin. When the hemorrhage is

large (2000 to 3000 mL), most of the blood is vomited. Because large quantities

of blood may be lost quickly, immediate correction of blood loss may be

required to prevent hemorrhagic shock. When the hemorrhage is small, much or

all of the blood is passed in the stools, which will appear tarry black because

of the digested hemoglobin. Management depends on the amount of blood lost and

the rate of bleeding.

The

nurse assesses the patient for faintness or dizziness and nausea, which may

precede or accompany bleeding. It is impor-tant to monitor vital signs

frequently and to evaluate the patient for tachycardia, hypotension, and

tachypnea. Other nursing in-terventions include monitoring the hemoglobin and

hematocrit, testing the stool for gross or occult blood, and recording hourly

urinary output to detect anuria or oliguria (absence or decreased urine

production).

Many

times the bleeding from a peptic ulcer stops sponta-neously; however, the

incidence of recurrent bleeding is high. Because bleeding can be fatal, the

cause and severity of the hem-orrhage must be identified quickly and the blood

loss treated to prevent hemorrhagic shock. Management of upper GI tract

bleeding consists of quickly determining the amount of blood lost and the rate

of bleeding, rapidly replacing the blood that has been lost, stopping the

bleeding, stabilizing the patient, and di-agnosing and treating the cause.

Related nursing and collabora-tive interventions include the following:

•

Inserting a peripheral IV line for the infusion of

saline or lactated Ringer’s solution and blood products. The nurse may need to

assist with the placement of a pulmonary artery catheter for hemodynamic

monitoring. Blood component therapy is initiated if there are signs of shock

(eg, tachycar-dia, sweating, coldness of the extremities).

•

Monitoring the hemoglobin and hematocrit to assist

in evaluating blood loss

•

Inserting an NG tube to distinguish fresh blood

from “coffee grounds” material, to aid in the removal of clots and acid, to

prevent nausea and vomiting, and to provide a means of monitoring further

bleeding

•

Administering a room-temperature lavage of saline

solution or water. This is controversial; some authorities recommend using ice

lavage (Yamada, 1999).

•

Inserting an indwelling urinary catheter and

monitoring urinary output

•

Monitoring vital signs and oxygen saturation and

adminis-tering oxygen therapy

•

Placing the patient in the recumbent position with

the legs elevated to prevent hypotension; or, to prevent aspiration from

vomiting, placing the patient on the left side

•

Treating hemorrhagic shock

If

bleeding cannot be managed by the measures described, other treatment

modalities may be used. Transendoscopic coagulation by laser, heat probe,

medication, a sclerosing agent, or a combina-tion of these therapies can halt

bleeding and make surgical inter-vention unnecessary. There is much debate

regarding how soon endoscopy should be performed. Some believe that endoscopy

should be performed in the first 24 hours after hemorrhage has been stabilized.

Others believe that endoscopy may be performed during acute bleeding, as long

as the esophageal or gastric area can be visualized (blood may decrease

visibility) (Yamada, 1999).

For

those who are unable to undergo surgery, selective em-bolization may be used.

This procedure involves forcing emboli of autologous blood clots with or

without Gelfoam (absorbable gelatin sponge) through a catheter in the artery to

a point above the bleeding lesion. A radiologist performs this procedure.

Rebleeding may occur and often warrants

surgical intervention. The nurse monitors the patient carefully so that bleeding

can be detected quickly. Signs of bleeding include tachycardia, tachypnea,

hypotension, mental confusion, thirst, and oliguria. If bleeding re-curs within

48 hours after medical therapy has begun, or if more than 6 to 10 units of

blood are required within 24 hours to main-tain blood volume, the patient is

likely to require surgery. Some physicians recommend surgical intervention if a

patient hemor-rhages three times. Other criteria for surgery are the patient’s

age (massive hemorrhaging is three times more likely to be fatal in those older

than 60 years of age); a history of chronic duodenal ulcer; and a coincidental

gastric ulcer (Yamada, 1999). The area of the ulcer is removed or the bleeding

vessels are ligated. Many patients also undergo procedures (eg, vagotomy and

pyloroplasty, gastrectomy) aimed at controlling the underlying cause of the

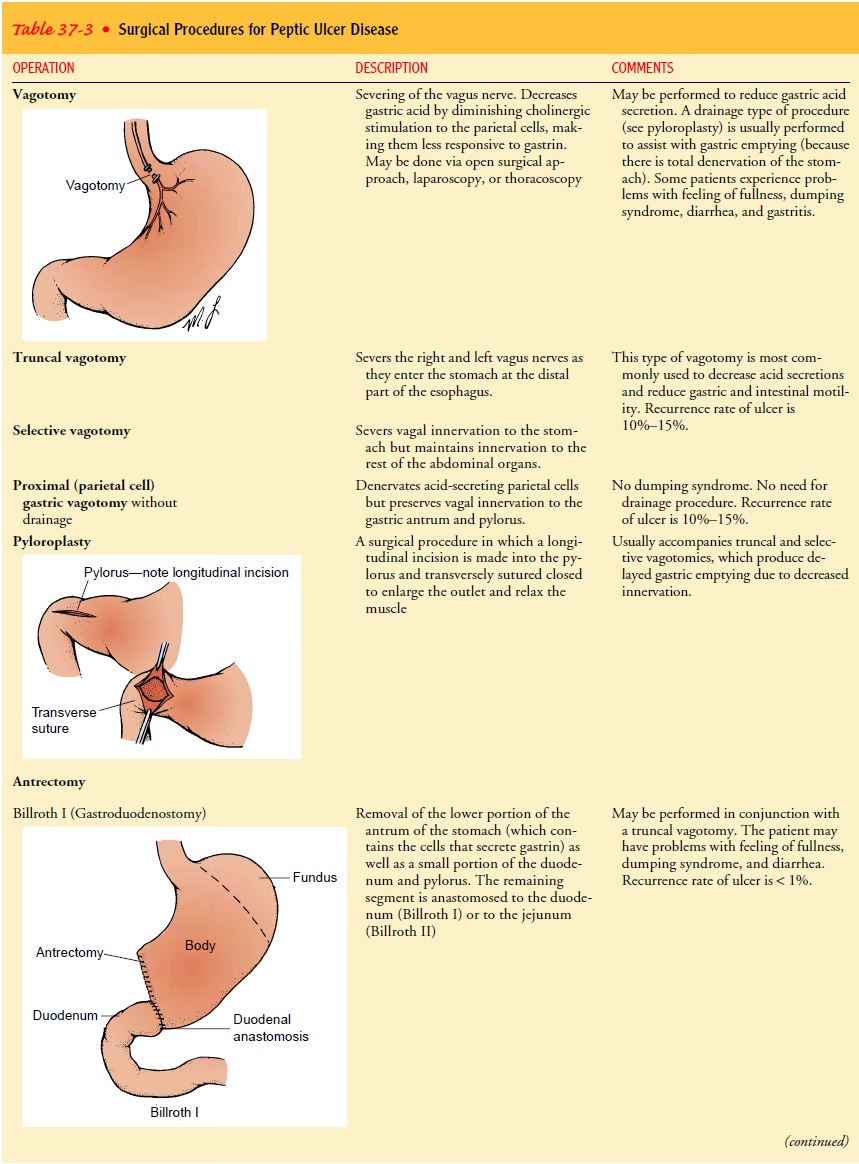

ulcers (see Table 37-3).

Perforation and Penetration

Perforation

is the erosion of the ulcer through the gastric serosa into the peritoneal

cavity without warning. It is an abdominal cat-astrophe and requires immediate

surgery. Penetration is erosion of the ulcer through the gastric serosa into

adjacent structures such as the pancreas, biliary tract, or gastrohepatic

omentum. Symp-toms of penetration include back and epigastric pain not relieved

by medications that were effective in the past. Like perforation, penetration

usually requires surgical intervention.

Signs

and symptoms of perforation include the following:

•

Sudden, severe upper abdominal pain (persisting and

in-creasing in intensity); pain may be referred to the shoulders, especially

the right shoulder, because of irritation of the phrenic nerve in the

diaphragm.

•

Vomiting and collapse (fainting)

•

Extremely tender and rigid (boardlike) abdomen

•

Hypotension and tachycardia, indicating shock

Because

chemical peritonitis develops within a few hours after perforation and is

followed by bacterial peritonitis, the perfora-tion must be closed as quickly

as possible. In a few patients, it may be deemed safe and advisable to perform

surgery for the ulcer dis-ease in addition to suturing the perforation.

Postoperatively,

the stomach contents are drained by means of an NG tube. The nurse monitors

fluid and electrolyte balance and assesses the patient for peritonitis or

localized infection (in-creased temperature, abdominal pain, paralytic ileus,

increased or absent bowel sounds, abdominal distention). Antibiotic therapy is

administered parenterally as prescribed.

Pyloric Obstruction

Pyloric

obstruction, also called gastric outlet obstruction (GOO), occurs when the area

distal to the pyloric sphincter becomes scarred and stenosed from spasm or

edema or from scar tissue that forms when an ulcer alternately heals and breaks

down. The pa-tient has nausea and vomiting, constipation, epigastric fullness,

anorexia, and, later, weight loss.

In

treating the patient with pyloric obstruction, the first con-sideration is to

insert an NG tube to decompress the stomach. Con-firmation that obstruction is

the cause of the discomfort is accomplished by assessing the amount of fluid

aspirated from the NG tube. A residual of more than 400 mL strongly suggests

ob-struction. Usually an upper GI study or endoscopy is performed to confirm

gastric outlet obstruction. Decompression of the stomach and management of

extracellular fluid volume and electrolyte bal-ances may improve the patient’s

condition and avert the need for surgical intervention. A balloon dilatation of

the pylorus via endoscopy may be beneficial. If the obstruction is unrelieved

by medical management, surgery (in the form of a vagotomy and antrectomy or gastrojejunostomy and

vagotomy) may be required.

PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE

Teaching Patients Self-Care

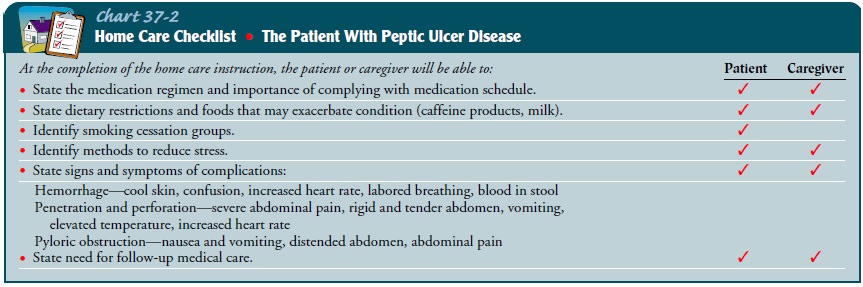

To manage ulcer disease successfully, the patient is instructed about the factors that will help or aggravate the condition (Chart 37-2). The nurse reviews information about medications to be taken at home, including name, dosage, frequency, and possible side ef-fects, stressing the importance of continuing to take medications even after signs and symptoms have decreased or subsided.

Then the patient is instructed to avoid certain

medications and foods that exacerbate symptoms as well as substances that have

acid-producing potential (eg, alcohol; caffeinated beverages such as coffee,

tea, and colas). It is important to counsel the patient to eat meals at regular

times and in a relaxed setting, and to avoid overeating. If relevant, the nurse

also informs the patient about the irritant effects of smoking on the ulcer and

provides infor-mation about smoking cessation programs.

The

nurse reinforces the importance of follow-up care for ap-proximately 1 year,

the need to report recurrence of symptoms, and the need for treating possible

problems that occur after surgery, such as intolerance to dairy products and

sweet foods.

Evaluation

EXPECTED PATIENT OUTCOMES

Expected

patient outcomes may include the following:

1) Reports freedom from

pain between meals

2) Feels less anxiety by

avoiding stress

3) Complies with

therapeutic regimen

a.

Avoids irritating foods and beverages

b.

Eats regularly scheduled meals

c.

Takes prescribed medications as scheduled

d.

Uses coping mechanisms to deal with stress

4) Maintains weight

5) Is free of complications

Related Topics