Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Gastric and Duodenal Disorders

Gastric and Duodenal Ulcers

Gastric and Duodenal Ulcers

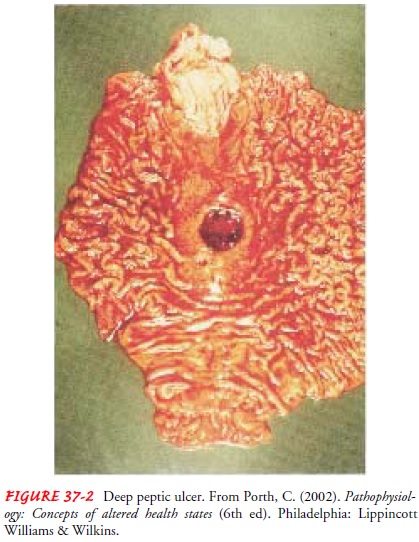

A peptic ulcer is an excavation (hollowed-out area) that forms in the

mucosal wall of the stomach, in the pylorus (opening between stomach and

duodenum), in the duodenum (first part of small intestine), or in the

esophagus. A peptic ulcer is frequently referred to as a gastric, duodenal, or

esophageal ulcer, depending on its location, or as peptic ulcer disease.

Erosion of a circumscribed area of mucous membrane is the cause (Fig. 37-2).

This erosion may extend as deeply as the muscle layers or through the muscle to

the peritoneum. Peptic ulcers are more likely to be in the duodenum than in the

stomach. As a rule they occur alone, but they may occur in multiples. Chronic

gastric ulcers tend to occur in the lesser curvature of the stomach, near the

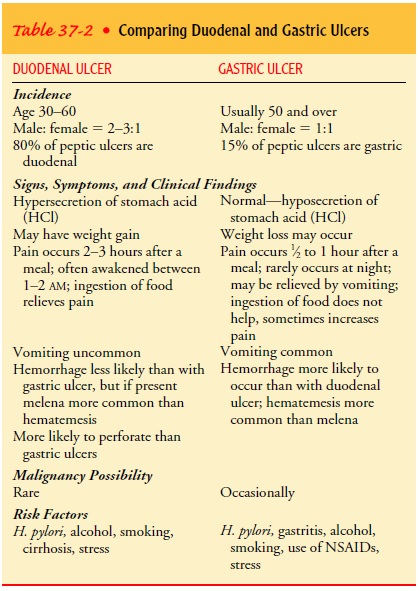

pylorus. Table 37-2 compares the features of gastric and duodenal ulcers.

Peptic ulcer disease occurs with the greatest frequency in people between the ages of 40 and 60 years. It is relatively uncommon in women of childbearing age, but it has been observed in children and even in infants. After menopause, the incidence of peptic ulcers in women is almost equal to that in men. Peptic ulcers in the body of the stomach can occur without excessive acid secretion.

In the past, stress and anxiety were thought to be causes of ulcers.

Research has identified that peptic ulcers result from infection with the

gram-negative bacteria H. pylori (Tytgat, 2000). However, ulcers do seem to

develop more commonly in people who are tense; whether this is a contributing

factor to the condition is uncertain. In addition, excessive secretion of HCl

in the stomach may contribute to the formation of gastric ulcers, and stress

may be associated with its increased secretion.

The ingestion of milk and caffeinated beverages, smoking, and alcohol

also may increase HCl secretion.Familial tendency may be a significant

predisposing factor. A further genetic link is noted in the finding that people

with blood type O are more susceptible to peptic ulcers than are those with

blood type A, B, or AB. There also is an association between duodenal ulcers

and chronic pulmonary disease or chronic renal disease. Other predisposing

factors associated with peptic ulcer include chronic use of NSAIDs, alcohol

ingestion, and excessive smoking.

Rarely, ulcers are caused by excessive amounts of the hormone gastrin,

produced by tumors. This Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES) consists of severe

peptic ulcers, extreme gastric hyperacidity, and gastrin-secreting benign or

malignant tumors of the pancreas. Stress ulcers, which are clinically different

from peptic ulcers, are ulcerations in the mucosa that can occur in the

gastroduodenal area. Stress ulcers may occur in patients who are exposed to

stressful conditions. Esophageal ulcers occur as a result of the backward flow

of HCl from the stomach into the esophagus (gastroesophageal reflux disease

[GERD]).

Pathophysiology

Peptic

ulcers occur mainly in the gastroduodenal mucosa because this tissue cannot

withstand the digestive action of gastric acid (HCl) and pepsin. The erosion is

caused by the increased concen-tration or activity of acid-pepsin, or by

decreased resistance of the mucosa. A damaged mucosa cannot secrete enough

mucus to act as a barrier against HCl. The use of NSAIDs inhibits the secretion

of mucus that protects the mucosa. Patients with duodenal ulcer disease secrete

more acid than normal, whereas patients with gas-tric ulcer tend to secrete

normal or decreased levels of acid.

ZES is

suspected when a patient has several peptic ulcers or an ulcer that is

resistant to standard medical therapy. It is identified by the following

findings: hypersecretion of gastric juice, duode-nal ulcers, and gastrinomas

(islet cell tumors) in the pancreas. Ninety percent of tumors are found in the

“gastric triangle,” which encompasses the cystic and common bile ducts, the

second and third portions of the duodenum, and the neck and body of the

pancreas. Approximately one third of gastrinomas are malig-nant. Diarrhea and

steatorrhea (unabsorbed fat in the stool) may be evident. The patient may have

coexisting parathyroid adeno-mas or hyperplasia and may therefore exhibit signs

of hyper-calcemia. The most common complaint is epigastric pain. H. pylori is not a risk factor for ZES.

Stress ulcer is the term given to the acute mucosal

ulceration ofthe duodenal or gastric area that occurs after physiologically

stress-ful events, such as burns, shock, severe sepsis, and multiple organ

traumas. These ulcers are most common in ventilator-dependent patients after

trauma or surgery. Fiberoptic endoscopy within 24 hours after injury reveals

shallow erosions of the stomach wall; by 72 hours, multiple gastric erosions

are observed. As the stress-ful condition continues, the ulcers spread. When

the patient re-covers, the lesions are reversed. This pattern is typical of

stress ulceration.

Differences

of opinion exist as to the actual cause of mucosal ulceration in stress ulcers.

Usually, it is preceded by shock; this leads to decreased gastric mucosal blood

flow and to reflux of duodenal contents into the stomach. In addition, large

quantities of pepsin are released. The combination of ischemia, acid, and

pepsin creates an ideal climate for ulceration.

Stress

ulcers should be distinguished from Cushing’s ulcers and Curling’s ulcers, two

other types of gastric ulcers. Cushing’s ulcers are common in patients with

trauma to the brain. They may occur in the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum and

are usu-ally deeper and more penetrating than stress ulcers. Curling’s ulcer is

frequently observed about 72 hours after extensive burns and involves the

antrum of the stomach or the duodenum.

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms

of an ulcer may last for a few days, weeks, or months and may disappear only to

reappear, often without an identifiable cause. Many people have symptomless

ulcers, and in 20% to 30% perforation or hemorrhage may occur without any

preceding manifestations.

As a

rule, the patient with an ulcer complains of dull, gnaw-ing pain or a burning

sensation in the midepigastrium or in the back. It is believed that the pain

occurs when the increased acid content of the stomach and duodenum erodes the

lesion and stimulates the exposed nerve endings. Another theory suggests that

contact of the lesion with acid stimulates a local reflex mech-anism that

initiates contraction of the adjacent smooth muscle. Pain is usually relieved

by eating, because food neutralizes the acid, or by taking alkali; however,

once the stomach has emptied or the alkali’s effect has decreased, the pain

returns. Sharply local-ized tenderness can be elicited by applying gentle

pressure to the epigastrium at or slightly to the right of the midline.

Other

symptoms include pyrosis

(heartburn), vomiting, con-stipation or diarrhea, and bleeding. Pyrosis is a

burning sensation in the esophagus and stomach that moves up to the mouth.

Heartburn is often accompanied by sour eructation, or burping, which is common

when the patient’s stomach is empty.

Although

vomiting is rare in uncomplicated duodenal ulcer, it may be a symptom of a

peptic ulcer complication. It results from obstruction of the pyloric orifice,

caused by either muscu-lar spasm of the pylorus or mechanical obstruction from

scarring or acute swelling of the inflamed mucous membrane adjacent to the

ulcer. Vomiting may or may not be preceded by nausea; usu-ally it follows a

bout of severe pain and bloating, which is relieved by ejection of the gastric

contents. Emesis often contains un-digested food eaten many hours earlier.

Constipation or diarrhea can occur, probably as a result of diet and

medications.

Fifteen

percent of patients with gastric ulcers experience bleed-ing. Patients may

present with GI bleeding as evidenced by the passage of tarry stools. A small

portion of patients who bleed from an acute ulcer have had no previous

digestive complaints, but they develop symptoms thereafter (Yamada, 1999).

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

A

physical examination may reveal pain, epigastric tenderness, or abdominal

distention. A barium study of the upper GI tract may show an ulcer; however,

endoscopy is the preferred diagnostic procedure because it allows direct

visualization of inflammatory changes, ulcers, and lesions. Through endoscopy,

a biopsy of the gastric mucosa and of any suspicious lesions can be obtained.

En-doscopy may reveal lesions that are not evident on x-ray studies because of

their size or location.

Stools

may be tested periodically until they are negative for oc-cult blood. Gastric

secretory studies are of value in diagnosing achlorhydria and ZES. H. pylori infection may be determined by

biopsy and histology with culture. There is also a breath test that detects H. pylori, as well as a serologic test

for antibodies to the H. pylori antigen.

Pain that is relieved by ingesting food orantacids and absence of pain on

arising are also highly suggestive of an ulcer.

Medical Management

Once

the diagnosis is established, the patient is informed that the problem can be

controlled. Recurrence may develop; however, peptic ulcers treated with

antibiotics to eradicate H. pylori

have a lower recurrence rate than those not treated with antibiotics. The goals

are to eradicate H. pylori and to

manage gastric acidity. Methods used include medications, lifestyle changes,

and surgical intervention.

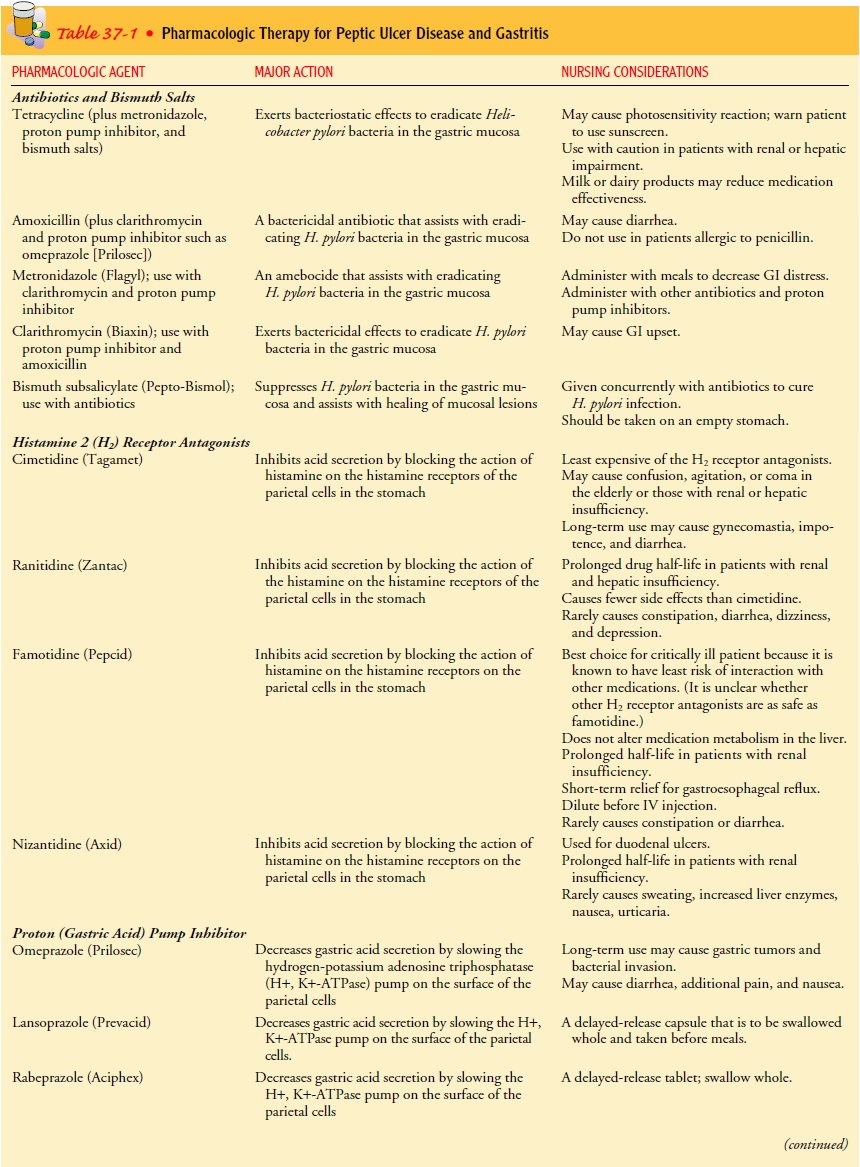

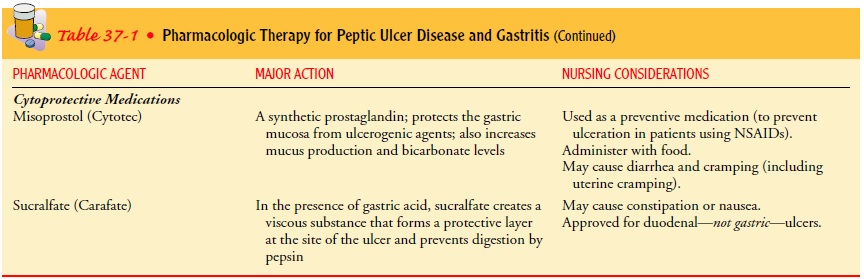

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Currently,

the most commonly used therapy in the treatment of ulcers is a combination of

antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors, and bismuth salts that suppresses or

eradicates H. pylori; hista-mine 2 (H2) receptor antagonists

and proton pump inhibitors are used to treat NSAID-induced and other ulcers not

associated with H. pylori ulcers.

Table 37-1 provides details about pharma-cologic treatment.

The

patient is advised to adhere to the medication regimen to ensure complete

healing of the ulcer. Because most patients be-come symptom-free within a week,

it becomes a nursing responsi-bility to stress the importance of following the

prescribed regimen so that the healing process can continue uninterrupted and

the re-turn of chronic ulcer symptoms can be prevented. Rest, sedatives, and

tranquilizers may add to the patient’s comfort and are pre-scribed as needed.

Maintenance dosages of H2 receptor antagonists are usually recommended for 1

year.

For

patients with ZES, hypersecretion of acid may be con-trolled with high doses of

H2 receptor antagonists.

These patients may require twice the normal dose, and dosages usually need to

be increased with prolonged use. Octreotide (Sandostatin), a med-ication that

suppresses gastrin levels, also may be prescribed.

Patients

at risk for stress ulcers may be treated prophylacti-cally with IV H2 receptor antagonists

and cytoprotective agents (e.g., misoprostol, sucralfate) because of the risk

for upper GI tract hemorrhage. Frequent gastric aspiration is performed to

allow monitoring of gastric secretion pH.

STRESS REDUCTION AND REST

Reducing

environmental stress requires physical and psychologi-cal modifications on the

patient’s part as well as the aid and coop-eration of family members and

significant others. The patient may need help in identifying situations that

are stressful or exhausting. A rushed lifestyle and an irregular schedule may

aggravate symp-toms and interfere with regular meals taken in relaxed settings

and with the regular administration of medications. The patient may benefit

from regular rest periods during the day, at least during the acute phase of

the disease. Biofeedback, hypnosis, or behavior modification may be helpful.

SMOKING CESSATION

Studies

have shown that smoking decreases the secretion of bicar-bonate from the

pancreas into the duodenum, resulting in increased acidity of the duodenum.

Research indicates that continuing to smoke cigarettes may significantly

inhibit ulcer repair. Therefore, the patient is strongly encouraged to stop

smoking. Smoking cessa-tion support groups and other smoking cessation

approaches are helpful for many patients (Eastwood, 1997).

DIETARY MODIFICATION

The

intent of dietary modification for patients with peptic ulcers is to avoid

oversecretion of acid and hypermotility in the GI tract. These can be minimized

by avoiding extremes of temperature and overstimulation from consumption of

meat extracts, alcohol, coffee (including decaffeinated coffee, which also

stimulates acid secretion) and other caffeinated beverages, and diets rich in

milk and cream (which stimulate acid secretion). In addition, an effort is made

to neutralize acid by eating three regular meals a day. Small, frequent

feedings are not necessary as long as an antacid or a histamine blocker is

taken. Diet compatibility becomes an in-dividual matter: the patient eats foods

that can be tolerated and avoids those that produce pain.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The

introduction of antibiotics to eradicate H.

pylori and of H2 receptor antagonists as treatment for ulcers has

greatly reduced the need for surgical interventions. However, surgery is usually

recom-mended for patients with intractable ulcers (those that fail to heal

after 12 to 16 weeks of medical treatment), life-threatening hem-orrhage,

perforation, or obstruction, and for those with ZES not re-sponding to

medications (Yamada, 1999). Surgical procedures include

vagotomy, with or without pyloroplasty, and the Billroth I and Billroth II

procedures. Patients who need ulcer surgery may have had a long illness. They

may be discouraged and have had interruptions in their work role and pressures

in their family life.

FOLLOW-UP CARE

Recurrence

within 1 year may be prevented with the prophylac-tic use of H2 receptor antagonists

given at a reduced dose. Not all patients require maintenance therapy; it may

be prescribed only for those with two or three recurrences per year, those who

have had a complication such as bleeding or outlet obstruction, or those who

are candidates for gastric surgery but are at too high a risk for surgery. The

likelihood of recurrence is reduced if the pa-tient avoids smoking, coffee

(including decaffeinated coffee) and other caffeinated beverages, alcohol, and

ulcerogenic medications (eg, NSAIDs).

Related Topics