Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Allergic Disorders

Latex Allergy - Allergic Disorders

LATEX ALLERGY

Latex

allergy, the allergic reaction to natural rubber proteins, has been implicated

in rhinitis, conjunctivitis, contact dermatitis, urticaria, asthma, and

anaphylaxis. Latex allergy and hypersensi-tivity were first reported in 1927

(Parslow et al., 2001). Although the prevalence of latex allergy is unknown,

since 1989 the num-ber of cases of latex allergy has steadily increased

(Parslow et al., 2001). This increase may be due to the widespread use of latex

gloves with implementation of universal and now standard pre-cautions in

response to the AIDS epidemic, changes in the man-ufacturing of gloves to speed

the process to meet the increased demand for gloves, and greater awareness

about latex allergy and its signs and symptoms.

Natural rubber latex is derived from the sap of the

rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis). The

conversion of the liquid rubber latex into a finished product entails the

addition of more than 200 chemi-cals. The proteins in the natural rubber latex

(Hevea proteins) or the various chemicals that are used in the manufacturing

process are thought to be the source of the allergic reactions. Not all

ob-jects composed of latex have the same ability to stimulate an al-lergic

response. For example, the antigenicity of latex gloves can differ widely

depending on their manufacturing method.

Populations at risk include health care workers,

patients with atopic allergies or multiple surgeries, people working in

factories manufacturing latex products, females, and patients with spina

bi-fida. Because more food handlers, hairdressers, auto mechanics, and police

are now wearing latex gloves, they may also be at risk for latex allergy. It is

estimated that 1% to 3% of the general population has an allergy to latex and

that 10% to 17% of health care workers are sensitized. Patients are at risk for

anaphylactic reactions due to con-tact with latex during medical treatments,

especially surgical pro-cedures. About 19% of anaphylactic reactions associated

with anesthesia are caused by allergy to latex (Brehler & Kütting, 2001).

Food that has been handled by individuals wearing

latex gloves may stimulate an allergic response. Cross-reactions have been

re-ported in people who are allergic to certain food products, such as kiwis,

bananas, pineapples, passion fruits, avocados, and chestnuts.

Routes

of exposure to latex products can be cutaneous, per-cutaneous, mucosal,

parenteral, and aerosol. The most frequent source of exposure is cutaneous,

which usually involves the wear-ing of natural latex gloves. The powder used to

facilitate putting on latex gloves can become a carrier of latex proteins from

the gloves; when the gloves are put on or removed, the particles be-come

airborne and can be inhaled or can settle on skin, mucous membranes, or

clothing. Mucosal exposure can occur from the use of latex condoms, catheters,

airways, and nipples. Parenteral exposure can occur from intravenous lines or

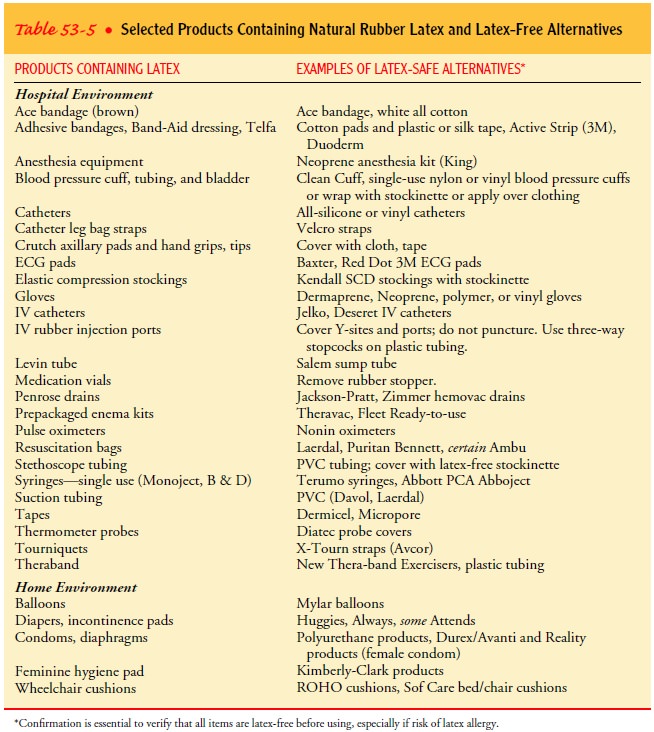

hemodialysis equip-ment. In addition to latex-derived medical devices, many

house-hold items also contain latex. Examples of medical and household items

containing latex and a list of alternative products are found in Table 53-5. It

is estimated that over 40,000 medical devices and nonmedical products contain

latex (Brehler & Kütting, 2001).

Clinical Manifestations

Several different types of reactions to latex are

possible. Irritant con-tact dermatitis, a nonimmunologic response, may be due

to me-chanical skin irritation or an alkaline pH associated with latex gloves.

Common symptoms of irritant dermatitis include erythema and pruritus. These

symptoms can be eliminated by changing glove brands or using powder-free

gloves. Use of hand lotion before don-ning latex gloves may worsen the symptoms

because lotions may leach latex proteins from the gloves, increasing skin

exposure and the risk of developing true allergic reactions (Burt, 1998).

Delayed hypersensitivity to latex, a type IV allergic reaction mediated by T cells in the immune system, is localized to the area of exposure and is characterized by symptoms of contact der-matitis, including vesicular skin lesions, papules, pruritus, edema, erythema, and crusting and thickening of the skin. These symp-toms usually appear on the back of the hands. This reaction is thought to be due to chemicals that are used for manufacturing latex products. It is the most common allergic reaction to latex. Although not usually life-threatening, delayed hypersensitivity reactions often require major changes in the patient’s home and work environment to avoid further exposure.

Immediate

hypersensitivity, a type I allergic reaction, is medi-ated by the IgE mast cell

system. Symptoms can include rhinitis, conjunctivitis, asthma, and anaphylaxis.

The term “latex allergy” is usually used to describe the type I reaction.

Clinical manifesta-tions have a rapid onset and can include urticaria,

wheezing, dys-pnea, laryngeal edema, bronchospasm, tachycardia, angioedema,

hypotension, and cardiac arrest.

Localized

itching, erythema, or local urticaria within minutes after exposure to latex

are often the initial symptoms. Symptoms of subsequent reactions can include

generalized urticaria, angio-edema, rhinitis, conjunctivitis, asthma, and

anaphylactic shock minutes after dermal or mucosal exposure to latex. An

increasing number of individuals allergic to latex experience severe reactions

characterized by generalized urticaria, bronchospasm, and hypo-tension (Brehler

& Kütting, 2001).

Diagnostic Testing

The diagnosis of latex allergy is based on the

history and diag-nostic test results (Parslow et al., 2001). Sensitization is

detected by skin testing, RAST, or ELISA. Skin tests have been unreliable

because of variability in the techniques used; however, a new stan-dardized

skin testing reagent is expected to be available in the near future. Skin tests

should be done only by clinicians who have ex-pertise in their administration

and interpretation and who have the necessary equipment available to treat

local or systemic aller-gic reactions to the reagent (Hamilton & Adkinson,

1998). Nasal challenge and dipstick tests may be useful in the future as

screen-ing tests for latex allergy.

Medical Management

The best treatment available for latex allergy is

the avoidance of latex products, but this is often difficult because of the

widespread use of latex-based products. Patients who have experienced an

anaphylactic reaction to latex should be instructed to wear med-ical

identification. Antihistamines and an emergency kit con-taining epinephrine

should be provided to these patients, along with instructions about emergency

management of latex allergy symptoms. Patients should be counseled to notify

all health care workers as well as local paramedic and ambulance companies

about their allergy. Warning labels can be attached to car win-dows to alert

police and paramedics about the driver’s or passen-ger’s latex allergy in case

of a motor vehicle crash. Individuals with latex allergy should be provided

with a list of alternative products and referred to local support groups; they

are also urged to carry their own supply of nonlatex gloves.

People

with type I latex sensitivity may be unable to continue to work if a latex-free

environment is not possible. This may occur with surgeons, dentists, operating

room personnel, or in-tensive care nurses. Occupational implications for

employees with type IV latex sensitivity are usually easier to manage by

changing to nonlatex gloves and avoiding direct contact with latex-based

medical equipment. Although latex-specific immuno-therapy has been reported,

this method of treatment remains ex-perimental (Brehler & Kütting, 2001).

Nursing Management

The nurse can assume a pivotal role in the management

of both patients and staff with latex allergies. All patients should be asked

about latex allergy, although special attention should be given to those at

particularly high risk (eg, patients with spina bifida, patients who have

undergone multiple surgical procedures). Every time an invasive procedure must

be performed, the nurse should consider the possibility of latex allergies.

Nurses working in op-erating rooms, intensive care units, short procedure

units, and emergency departments need to pay particular attention to latex

allergy.

Although

the type I reaction is the most significant of the re-actions to latex, care

must be taken in the presence of irritant contact dermatitis and delayed

hypersensitivity reaction to avoid further exposure of the individual to latex.

Patients with latex al-lergy are advised to notify their health care providers

and to wear a medical information bracelet. Patients must become knowl-edgeable

about what products contain latex and what products are safe, nonlatex alternatives.

They must also become knowl-edgeable about signs and symptoms of latex allergy

and emer-gency treatment and self-injection of epinephrine in case of allergic

reaction.

Nurses can be instrumental in establishing and

participating in multidisciplinary committees to address latex allergy and to

promote a latex-free environment. Latex allergy protocols and ed-ucation of

staff about latex allergy and precautions are important strategies to reduce

this growing problem and to ensure assess-ment and prompt treatment of affected

individuals.

Related Topics