Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Allergic Disorders

Diagnostic Evaluation of Patients With Allergic Disorders

Diagnostic Evaluation

Diagnostic evaluation of the patient with

allergic disorders com-monly includes blood tests, smears of body secretions,

skin tests, and the radioallergosorbent test (RAST). Results of laboratory

blood studies provide supportive data for various diagnostic pos-sibilities;

however, they are not the major criteria for the diagno-sis of allergic

disease.

COMPLETE BLOOD COUNT WITH DIFFERENTIAL

The white blood cell (WBC) count is usually

normal except with infection. Eosinophils, granular leukocytes, normally make

up 1% to 3% of the total number of WBCs. A level between 5% and 15% is

nonspecific but does suggest allergic reaction. Higher levels are considered

moderate and severe. In moderate eosinophilia, 15% to 40% of blood leukocytes

as eosinophils are found in patients with allergic disorders as well as in

patients with malig-nancy, immunodeficiencies, parasitic infections, and

congenital heart disease, and those receiving peritoneal dialysis. In severe

eosinophilia, 50% to 90% of blood leukocytes as eosinophils are found in the

idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome.

EOSINOPHIL COUNT

An actual count of eosinophils may be

obtained from blood sam-ples or smears of secretions. A total eosinophil count

can be ob-tained from a blood sample by using special diluting fluids that

hemolyze erythrocytes and stain the eosinophils. During symp-tomatic episodes,

smears obtained from nasal secretions, con-junctival secretions, and sputum of

atopic patients usually reveal eosinophils, indicative of an active allergic

response.

TOTAL SERUM IMMUNOGLOBULIN E LEVELS

High

total serum IgE levels support the diagnosis of atopic dis-ease. A normal IgE

level, however, does not exclude the diagno-sis of an allergic disorder. IgE

levels are not as sensitive as the paper radioimmunosorbent test (PRIST) and

the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Indications for determining IgE

levels include the following:

· Evaluation of

immunodeficiency

· Evaluation of drug

reactions

· Initial laboratory

screening for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

· Evaluation of allergy

among children with bronchiolitis

· Differentiation of

atopic and nonatopic eczema

· Differentiation of

atopic and nonatopic asthma and rhinitis

SKIN TESTS

Skin

testing entails the intradermal injection or superficial appli-cation

(epicutaneous) of solutions at several sites. Depending on the suspected cause

of allergic signs and symptoms, several dif-ferent solutions may be applied at

several separate sites. These so-lutions contain individual antigens

representing an assortment of allergens, including pollen, most likely to be

implicated in the pa-tient’s disease. Positive reactions (wheal and flare) are

clinically significant when correlated with the history, physical findings, and

results of other laboratory tests.

The results of skin tests complement the data obtained from the history. They indicate which of several antigens are most likely to provoke symptoms and provide some clue to the inten-sity of the patient’s sensitization. The dosage of the antigen (al-lergen) injected is also important. Most patients are hypersensitive to more than one pollen. Under testing conditions, they may not react (although they usually do) to the specific pollens that induce their attacks.

In

cases of doubt about the validity of the skin tests, a RAST or a provocative

challenge test may be performed. If a skin test is indicated, there is a

reasonable suspicion that a specific allergen is producing symptoms in an

allergic patient. Several precau-tionary steps, however, must be observed

before skin testing with allergens:

· Testing is not performed

during periods of bronchospasm.

· Epicutaneous tests

(scratch or prick tests) are performed be-fore other testing methods in an

effort to minimize the risk of systemic reaction.

· Emergency equipment must

be readily available to treat anaphylaxis.

Types of Skin Tests

The methods of skin testing include prick

skin tests, scratch tests, and intradermal skin testing (Fig. 53-3). After

prick or scratch tests, intradermal skin testing is performed with allergens

that did not elicit positive reactions. Because a larger antigen challenge is

being used, local or systemic reactions could occur if the same antigens that

produced positive skin or scratch reactions are used. The back is the most

suitable area of the body for skin testing be-cause it permits the performance

of many tests. The multitest ap-plicator is a commercially available device

with multiple test heads that allows simultaneous administration of antigens by

multiple punctures at different sites.

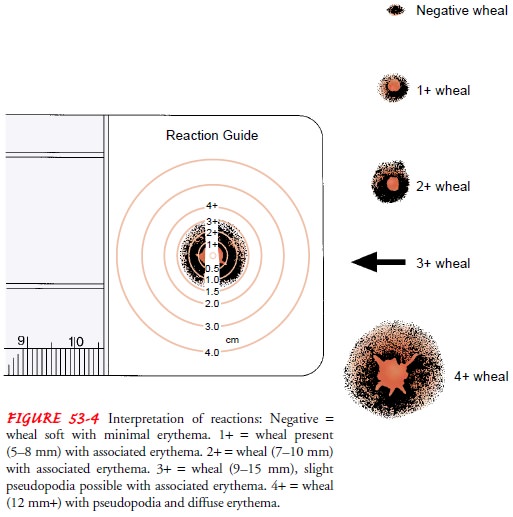

Interpretation of Skin Test Results

Familiarity with and consistent use of a

grading system are es-sential. The grading system used should be identified on

a skin test sheet for later interpretation. A positive reaction, evidenced by

the appearance of an urticarial wheal (round, reddened skin elevation) (Fig. 53-4),

localized erythema (diffuse redness)

in the area of inoculation or contact, or pseudopodia (irregular projection at

the end of a wheal) with associated erythema is considered indicative of

sensitivity to the corresponding antigen.

There

may be false-negative results due to improper tech-nique, outdated allergen

solutions, and prior use of medications that suppress skin reactivity.

Corticosteroids and antihista-mines, including allergy medications, suppress

skin test reactiv-ity and are usually withheld 48 to 96 hours before testing,

depending on the duration of their activity. False-positive skin tests may

result from improper preparation or administration of allergen solutions.

Interpretation of positive or negative skin tests must be based on the history, physical examination, and other laboratory test results. The following guidelines are used for the interpretation of skin test results:

· Skin tests are more

reliable for diagnosing atopic sensitivity in patients with allergic

rhinoconjunctivitis than in patients with asthma.

· Positive skin tests

correlate highly with food allergy.

· The use of skin tests to diagnose immediate hypersensitivity to

medications is limited because metabolites of medica-tions, not the medications

themselves, are usually responsi-ble for causing hypersensitivity.

PROVOCATIVE TESTING

Provocative testing involves the direct

administration of the sus-pected allergen to the sensitive tissue, such as the

conjunctiva, nasal or bronchial mucosa, or gastrointestinal tract (by ingestion

of the allergen) with observation of target organ response. This type of

testing is helpful in identifying clinically significantaller-gens in patients

with a large number of positive tests.Major dis-advantages of this type of

testing are the limitation of one antigen per session and the risk of producing

severe symptoms, particu-larly bronchospasm, in patients with asthma.

RADIOALLERGOSORBENT TEST

RAST is a radioimmunoassay that measures

allergen-specific IgE. A sample of the patient’s serum is exposed to a variety

of sus-pected allergen particle complexes. If antibodies are present, they will

combine with radiolabeled allergens. After the serum is cen-trifuged,

radioimmunoassay detects the allergen-specific IgE an-tibody. Test results are

then compared with control values. In addition to detecting an allergen, RAST

indicates the quantity of allergen necessary to evoke an allergic reaction.

Values are re-ported on a scale from 0 to 5. Values of 2+ or greater are

consid-ered significant. The major advantages of RAST over other tests include

decreased risk of systemic reaction, stability of antigens, and lack of

dependence on skin reactivity modified by medications. The major disadvantages include the

limited allergen se-lection, reduced sensitivity compared with intradermal skin

tests, lack of immediate results, and cost.

Related Topics