Chapter: Essentials of Anatomy and Physiology: The Digestive System

Large Intestine - Anatomy and Physiology

LARGE INTESTINE

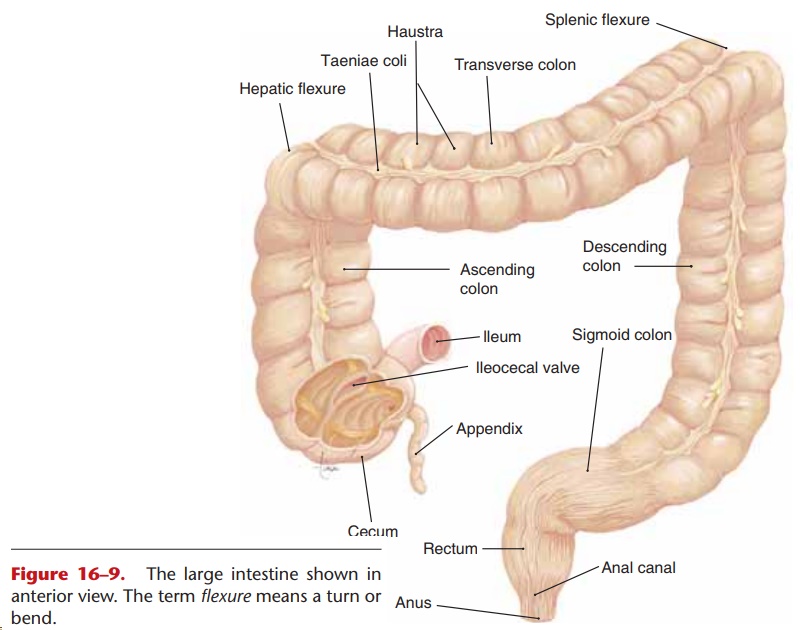

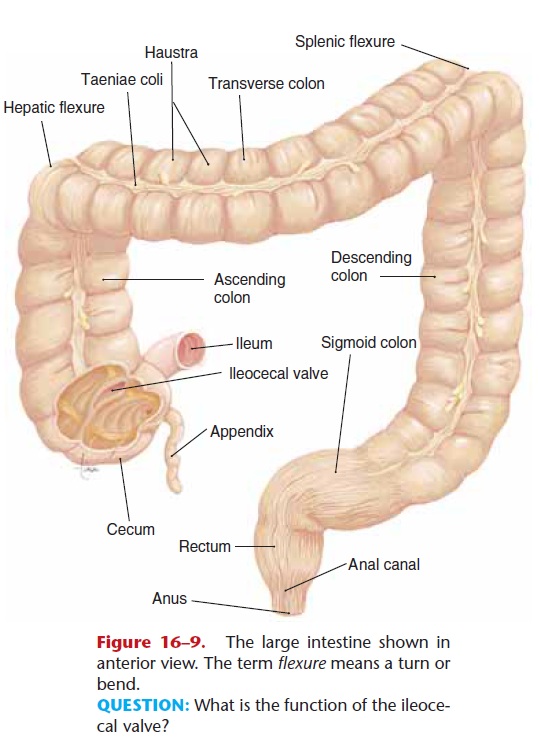

The large intestine, also called the colon, is approx-imately 2.5 inches (6.3 cm) in diameter and 5 feet (1.5 m) in length. It extends from the ileum of the small intestine to the anus, the terminal opening. The parts of the colon are shown in Fig. 16–9. The cecum is the first portion, and at its junction with the ileum is the ileocecal valve, which is not a sphincter but serves the same purpose. After undigested food (which is now mostly cellulose) and water pass from the ileum into the cecum, closure of the ileocecal valve prevents the backflow of fecal material.

Figure 16–9. The large intestine shown in anterior view. The term flexure means a turn or bend.

QUESTION: What is the function of the ileoce-cal valve?

Attached to the cecum is the appendix, a small, dead-end tube with abundant lymphatic tissue. The appendix seems to be a vestigial organ, that is, one whose size and function seem to be reduced. Although there is abundant lymphatic tissue in the wall of the appendix, the possibility that the appendix is con-cerned with immunity is not known with certainty. Appendicitis refers to inflammation of the appendix, which may occur if fecal material becomes impacted within it. This usually necessitates anappendectomy, the surgical removal of the appendix.

The remainder of the colon consists of the ascend-ing, transverse, and descending colon, which encircle the small intestine; the sigmoid colon, which turns medially and downward; the rectum; and the anal canal. The rectum is about 6 inches long, and the anal canal is the last inch of the colon that surrounds the anus. Clinically, however, the terminal end of the colon is usually referred to as the rectum.

No digestion takes place in the colon. The only secretion of the colonic mucosa is mucus, which lubri-cates the passage of fecal material. The longitudinal smooth muscle layer of the colon is in three bands called taeniae coli. The rest of the colon is “gathered” to fit these bands. This gives the colon a puckered appearance; the puckers or pockets are called haustra, which provide for more surface area within the colon.

The functions of the colon are the absorption of water, minerals, and vitamins and the elimination of undigestible material. About 80% of the water that

Positive and negative ions are also absorbed. The vita-mins absorbed are those produced by the normal flora, the trillions of bacteria that live in the colon. Vitamin K is produced and absorbed in amounts usu-ally sufficient to meet a person’s daily need. Other vitamins produced in smaller amounts include riboflavin, thiamin, biotin, and folic acid. Everything absorbed by the colon circulates first to the liver by way of portal circulation. Yet another function of the normal colon flora is to inhibit the growth of pathogens.

ELIMINATION OF FECES

Feces consist of cellulose and other undigestible mate-rial, dead and living bacteria, and water. Elimination of feces is accomplished by the defecation reflex, a spinal cord reflex that may be controlled voluntarily. The rectum is usually empty until peristalsis of the colon pushes feces into it. These waves of peristalsis tend to occur after eating, especially when food enters the duodenum. The wall of the rectum is stretched by the entry of feces, and this is the stimulus for the defe-cation reflex.

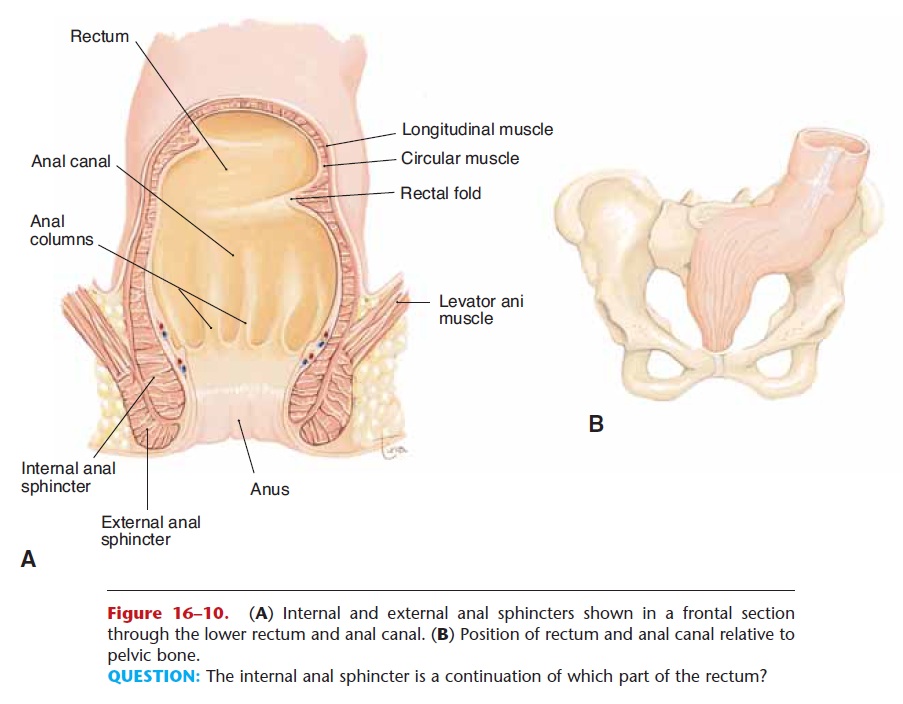

Stretch receptors in the smooth muscle layer of the rectum generate sensory impulses that travel to the sacral spinal cord. The returning motor impulses cause the smooth muscle of the rectum to contract. Surrounding the anus is the internal anal sphincter, which is made of smooth muscle. As part of the reflex, this sphincter relaxes, permitting defecation to take place.

The external anal sphincter is made of skeletal muscle and surrounds the internal anal sphincter (Fig. 16–10). If defecation must be delayed, the external sphincter may be voluntarily contracted to close the anus. The awareness of the need to defecate passes as the stretch receptors of the rectum adapt. These receptors will be stimulated again when the next wave of peristalsis reaches the rectum.

Related Topics