Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuropsychology

Executive Functioning and the Frontal Lobes

Executive Functioning and the

Frontal Lobes

Most researchers now agree that the study of

frontal lobes repre-sents an important aspect of attempts to understand of

humans’ higher mental functions, such as planning, decision-making, rea-soning

and judgment, which are often referred to as executive processes.

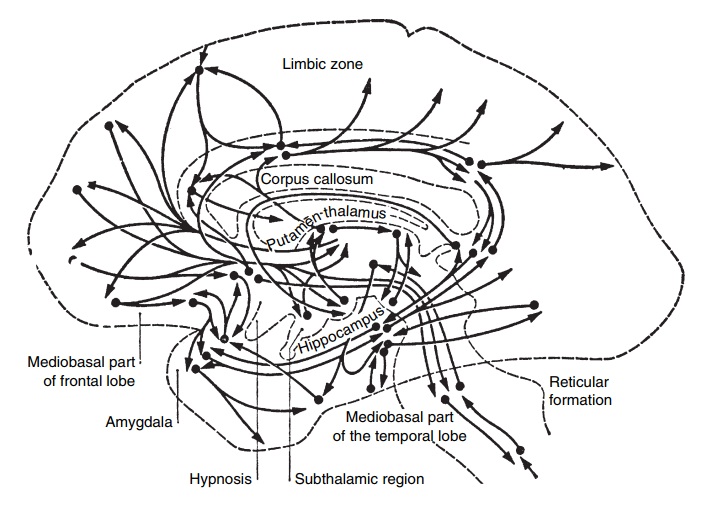

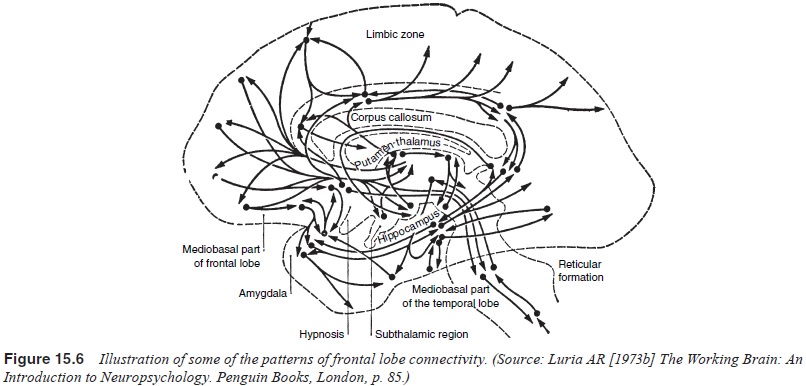

The frontal lobes of the human brain comprise all

the tis-sue anterior to the central sulcus. Four major subdivisions of the

frontal lobes have been suggested: 1) the motor area; 2) the pre-motor area; 3)

the prefrontal area, and 4) the basomedial portion of the lobes (Walsh, 1994).

Two prefrontal areas, namely, the orbitomedial

prefrontal cortex and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, have been targeted in

much of the research concerning executive processes. The func-tional role of

the frontal system in providing executive control to behavior is probably

related to the extensive reciprocal anatomical connectivity between the frontal

lobes and other brain regions involved in information processing. Numerous

afferent and ef-ferent connections of the frontal lobe have been demonstrated.

The extracortical and transcortical connections of the frontal lobes are

exceedingly complex, especially where the prefrontal cortex is involved (Kolb

and Wishaw, 1990). In general, brain connectivity encompasses three major

types: cortical–cortical, thalamic–cortical, and subcortical–cortical (Figure

15.6). For a detailed review of brain connectivity, the reader is referred to

the works of Pandya and Yeterian (1984) and Goldman-Rakic (1988).

Cortical–cortical connections of the frontal lobes

take on a number of distinct forms (Kolb and Wishaw, 1990). First, as

pre-viously mentioned, connections within the frontal lobes them-selves involve

projections from tertiary cortex in the prefrontal areas to the premotor cortex

and to the motor cortex. Secondly, there are reciprocal connections between the

prefrontal cortex (Brodmann’s areas 8, 9 and 46) and the temporal, auditory and

visual association regions, as well as the medial temporal lobes. Thirdly,

there is another set of reciprocal connections connecting the prefrontal areas

and the anterior and medial temporal regions. Fourthly, there are connections

between prefrontal areas and the limbic system, including a reciprocal

connection between the amygdala and the frontal lobe.

Thalamic–cortical connections include projections

to the prefrontal lobe from the pulvinar, anterior nuclei and dorsomedial

nucleus of the thalamus. In addition, via the dorsomedial nucleus, information

from limbic areas and the hypothalamus is relayed to the frontal lobes for

processing of emotions and internal states.

Subcortical–cortical connections include

projections from the frontal cortex to various subcortical structures

includ-ing the caudate nucleus, superior colliculus and hypothalamus.

Particular attention has been paid to the interconnectivity of the frontal lobe

and basal ganglia via the corticostriate projection system. Lesions in either

area are associated with similar cogni-tive impairments, such as decreased

cognitive flexibility or set switching (Eslinger and Grattan, 1993

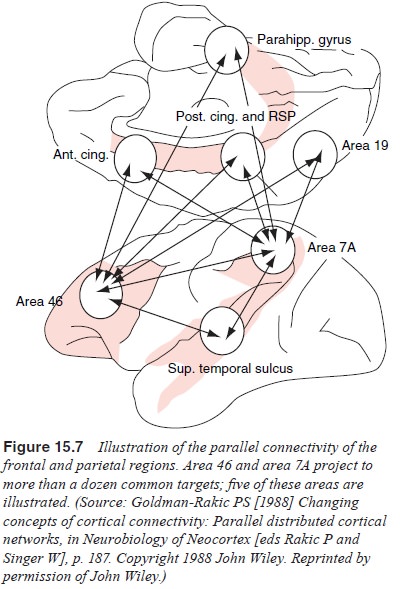

Examination of the connectivity of the frontal lobes has revealed that the pattern of connectivity is best viewed from within the context of the parallel and distributed anatomical network (Figure 15.7).

Related Topics