Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Equipment & Monitors : Non cardiovascular Monitoring

Evoked Potentials - Neurological System Monitors

EVOKED POTENTIALS

Indications

Indications for intraoperative

monitoring of evokedpotentials (EPs)

include surgical procedures asso-ciated with possible neurological injury:

spinal fusion with instrumentation, spine and spinal cord tumor resection,

brachial plexus repair, thoracoab-dominal aortic aneurysm repair, epilepsy

surgery, and cerebral tumor resection. Ischemia in the spi-nal cord or cerebral

cortex can be detected by EPs. EP monitoring facilitates probe localization

during stereotactic neurosurgery. Auditory EPs have also been used to assess

the effects of general anesthesia on the brain. The middle latency auditory EP

may be a more sensitive indicator than BIS in regard to anesthetic depth. The

amplitude and latency of this signal following an auditory stimulus is

influenced by anesthetics.

Contraindications

Although there are no specific

contraindications for somatosensory-evoked potentials (SEPs), this modality is

severely limited by the availability of monitoring sites, equipment, and

trained personnel. Sensitivity to anesthetic agents can also be a limit-ing

factor, particularly in children. Motor-evoked potentials (MEPs) are

contraindicated in patients with retained intracranial metal, a skull defect,

and implantable devices, as well as after seizures and any major cerebral

insult. Brain injury secondary to repetitive stimulation of the cortex and

inducement of seizures is a concern with MEPs.

Techniques & Complications

EP monitoring noninvasively assesses

neural func-tion by measuring electrophysiological responses to sensory or

motor pathway stimulation. Commonly monitored EPs are brainstem auditory evoked

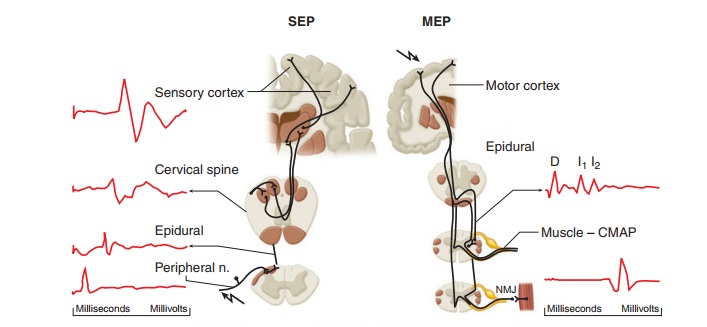

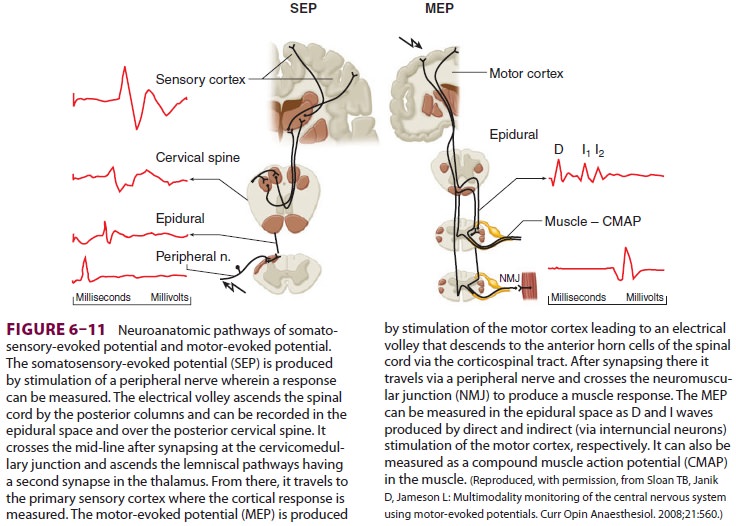

responses (BAERs), SEPs, and increasingly, MEPs (Figure 6–11).

For SEPs, a brief electrical current is

delivered to a sensory or mixed peripheral nerve by a pair of electrodes. If

the intervening pathway is intact, a nerve action potential will be transmitted

to the contralateral sensory cortex to produce an EP. This potential can be

measured by cortical surface electrodes, but is usually measured by scalp

elec-trodes. To distinguish the cortical response to a specific stimulus,

multiple responses are averaged and background noise is eliminated. EPs are

repre-sented by a plot of voltage versus time. The result-ing waveforms are

analyzed for their poststimulus latency (the time between stimulation and

potential detection) and peak amplitude. These are compared with baseline

tracings. Technical and physiological causes of a change in an EP must be

distinguished from changes due to neural damage. Complications of EP monitoring

are rare, but include skin irrita-tion and pressure ischemia at the sites of

electrode application.

Clinical Considerations

EPs are altered by many variables other

than neural damage. The effect of anesthetics is complex and not easily

summarized. In general, balanced anesthetic techniques (nitrous oxide,

neuromuscular block-ing agents, and opioids) cause minimal changes, whereas

volatile agents (halothane, sevoflurane, desflurane, and isoflurane) are best

avoided or used at a constant low dose. Early-occurring (spe-cific) EPs are

less affected by anesthetics than are late-occurring (nonspecific) responses.

Changes in BAERs may provide a measure of the depth of anes-thesia.

Physiological (eg, blood pressure, tempera-ture, and oxygen saturation) and

pharmacological factors should be kept as constant as possible.

Persistent obliteration of EPs is

predictive of postoperative neurological deficit. Although SEPs usually

identify spinal cord damage, because of their different anatomic pathways, sensory (dorsal spinal cord) EP

preservation does not guarantee normal motor

(ventral spinal cord) function (false negative). Furthermore, SEPs elicited

from pos-terior tibial nerve stimulation cannot distinguish between peripheral

and central ischemia (false posi-tive). Techniques that elicit MEPs by using

transcra-nial magnetic or electrical stimulation of the cortex allow the

detection of action potentials in the mus-cles if the neural pathway is intact.

The advantage of using MEPs as opposed to SEPs for spinal cord monitoring is

that MEPs monitor the ventral spi-nal cord, and if sensitive and specific

enough, can be used to indicate which patients might develop a postoperative

motor deficit. MEPs are more sensi-tive to spinal cord ischemia than are SEPs.

The same considerations for SEPs are applicable to MEPs in that they are

affected by volatile inhalational agents, high-dose benzodiazepines, and

moderate hypothermia (temperatures less than 32°C). MEPsrequire monitoring of

the level of neuromuscu-lar blockade. Close communication with a

neu-rophysiologist is essential prior to the start of any case where these

monitors are used to review the optimal anesthetic technique to ensure

monitoring integrity. MEPs are sensitive to volatile anesthet-ics.

Consequently, intravenous techniques are often preferred.

Related Topics