Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Female Physiologic Processes

Ectopic Pregnancy - Management of Normal and Altered Female Reproductive Function

ECTOPIC

PREGNANCY

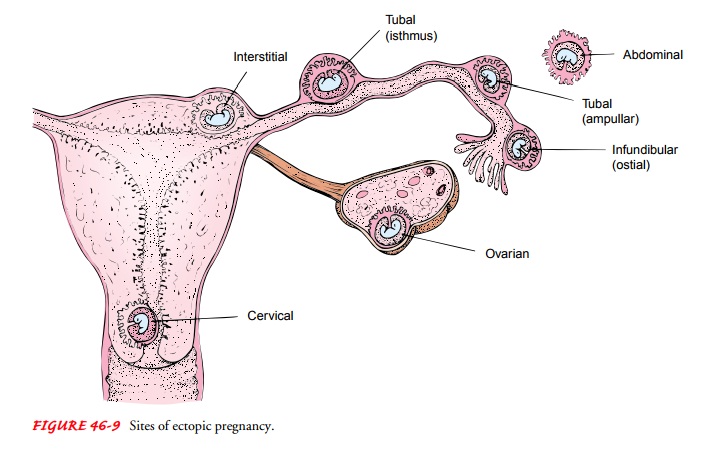

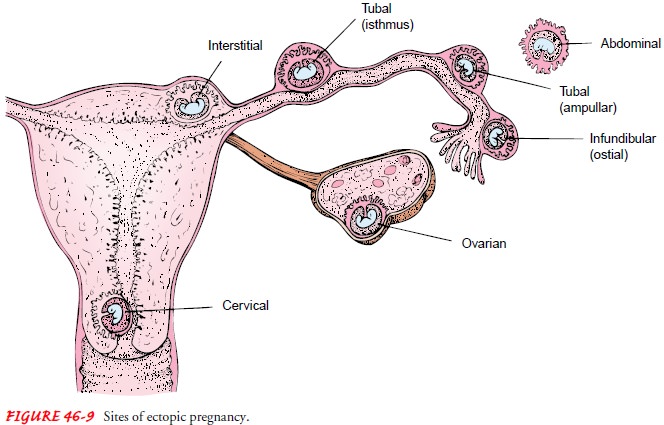

The

incidence of ectopic pregnancy is on the rise: it occurs in 2% of pregnancies

(Lemus, 2000). It occurs when a fertilized ovum (a blastocyst) becomes

implanted on any tissue other than the uterine lining (eg, the fallopian tube,

ovary, abdomen, or cervix; Fig. 46-9). The most common site of ectopic

implantation is the fallopian tube.

Possible

causes include salpingitis, peritubal adhesions (after pelvic infection,

endometriosis, appendicitis), structural abnor-malities of the fallopian tube

(rare and usually related to DES ex-posure), previous ectopic pregnancy (after

one ectopic pregnancy, the risk of recurrence is 7% to 15%; Lemus, 2000),

previous tubal surgery, multiple previous induced abortions (particularly if

fol-lowed by infection), tumors that distort the tube, and IUD and

progestin-only contraceptives. PID appears to be the major risk factor for

ectopic pregnancy. Improved antibiotic therapy for PID usually prevents total

tubal closure but may leave a stricture or nar-rowing, predisposing the woman

to ectopic implantation. The odds of recurrent ectopic pregnancy are three

times higher if an infectious pathology was the cause of the first one. If a

woman has a second ectopic pregnancy, assisted reproduction is considered.

The rate of tubal pregnancies has increased in disproportion to population growth. Ectopic pregnancies are being diagnosed sooner and more often because of advanced diagnostic tech-niques. Moreover, they are being treated conservatively before emergency rupture and hemorrhage occur. It may be that the in-creased numbers result from better diagnostic techniques. Con-servative treatment makes ectopic pregnancy less life-threatening than previously, but this condition persists as the leading cause of pregnancy-related death in the first trimester and the second lead-ing cause of maternal mortality in the United States. Ectopic pregnancy is also a complication of IVF.

Clinical Manifestations

Early

intervention decreases rupture, minimizes tubal damage, and usually avoids the

need for surgery. Signs and symptoms vary depending on whether tubal rupture

has occurred. Delay in men-struation from 1 to 2 weeks followed by slight

bleeding (spotting) or a report of a slightly abnormal period suggests the

possibility of an ectopic pregnancy. Symptoms may begin late, with vague soreness

on the affected side, probably due to uterine contractions and distention of

the tube. Typically, the patient experiences sharp, colicky pain. Most patients

experience pelvic or abdominal pain and some spotting or bleeding.

Gastrointestinal symptoms, dizziness, or lightheadedness is common. The patient

frequently thinks the abnormal bleeding is a menstrual period, especially if a

recent period occurred and was normal.

If implantation occurs in the fallopian tube, the tube becomes more and more distended and can rupture if the ectopic pregnancy remains undetected for 4 to 6 weeks or longer after conception. When the tube ruptures, the ovum is discharged into the abdom-inal cavity.

When

tubal rupture occurs, the woman experiences agonizing pain, dizziness,

faintness, and nausea and vomiting. These symp-toms are related to the

peritoneal reaction to blood escaping from the tube. Air hunger and symptoms of

shock may occur, and the signs of hemorrhage—rapid and thready pulse, decreased

blood pressure, subnormal temperature, restlessness, pallor, and sweating—are

evident. Later, the pain becomes generalized in the abdomen and radiates to the

shoulder and neck because of accu-mulating intraperitoneal blood that irritates

the diaphragm.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

During

vaginal examination, a large mass of clotted blood that has collected in the

pelvis behind the uterus or a tender adnexal mass may be palpable. If an

ectopic pregnancy is suspected, the patient is evaluated by sonography and the

beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels. If the ultrasound

results are inconclu-sive, the beta-hCG test is repeated to evaluate the rate

of rise in the level. The levels of hCG (the diagnostic hormone of pregnancy) double

in early normal pregnancies every 3 days but are reduced in abnormal or ectopic

pregnancies. A less-than-normal increase is cause for suspicion. Serum

progesterone levels are also mea-sured. Levels under 5 ng/mL are considered

abnormal; levels over 25 ng/mL are associated with a normally developing

pregnancy. Urine tests for pregnancy are not helpful in ectopic pregnancies.

Ultrasound

can detect a pregnancy between 5 and 6 weeks from the last menstrual period.

Detectable fetal heart movement outside the uterus on ultrasound is firm

evidence of an ectopic pregnancy. On occasion, an ultrasound study is not

definitive and the diagnosis must be made with combined diagnostic aids (hCG

level, ultrasound, pelvic examination, and clinical judgment). Studies using

ultrasound with Doppler flow, in which color in-dicates perfusion, are helpful.

Occasionally,

the clinical picture makes the diagnosis rela-tively easy. However, when the

clinical signs and symptoms are questionable, which is often the case, other

procedures have value. Laparoscopy is used because the physician can visually

de-tect an unruptured tubal pregnancy and thereby circumvent the risk of its

rupture.

Medical Management

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

When

surgery is performed early, almost all patients recover rapidly; if tubal

rupture occurs, mortality increases. The type of surgery is determined by the

size and extent of local tubal dam-age. Conservative surgery would include

“milking” an ectopic pregnancy from the tube. Resection of the involved fallopian

tube with end-to-end anastomosis may be effective. Some surgeons at-tempt to

salvage the tube with a salpingostomy, which involves opening and evacuating

the tube and controlling bleeding. More extensive surgery includes removing the

tube alone (salpingec-tomy) or with the ovary (salpingo-oophorectomy).

Depending on the amount of blood lost, blood component therapy and treat-ment

of hemorrhagic shock may be necessary before and during surgery. Surgery may

also be indicated in women unlikely to comply with close monitoring or those

who live too far away from a health care facility to obtain the monitoring

needed with nonsurgical management.

Methotrexate,

a chemotherapeutic agent and folic acid antag-onist, is used after surgery to

treat any remaining embryonic or early pregnancy tissue, as indicated by a

persistent or rising beta-hCG level. The beta-hCG test is repeated 2 weeks

after surgery to ensure a falling level.

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Another

option is the use of methotrexate without surgery. Because this medication

stops the pregnancy from progressing by interfer-ing with DNA synthesis and the

multiplication of cells, it interrupts early, small, unruptured tubal

pregnancies. Patients must be he-modynamically stable, have no active renal or

hepatic disease, have no evidence of thrombocytopenia or leukopenia, and have a

very small, unruptured tubal pregnancy on ultrasound. The medication is

administered intramuscularly or intravenously. Some pa-tients may be treated

with intratubal injection of methotrexate. Complete blood count, blood typing,

and tests of liver and renal function are conducted to monitor the patient. The

patient is ad-vised to refrain from alcohol, intercourse, and vitamins with

folic acid until the pregnancy is resolved because these may exacerbate the

adverse effects of methotrexate. Abdominal pain may occur within 5 to 10 days

and may indicate termination of the pregnancy. This requires careful assessment

by the health care provider. Serum levels of hCG are monitored carefully, and these

levels should grad-ually decrease. Ultrasounds may also be used for monitoring.

Side effects of methotrexate include stomatitis and diarrhea, bone mar-row

suppression, impaired liver function, dermatitis, and pleuritis.

Related Topics