Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Female Physiologic Processes

Assessment of Female Physiologic Processes: Health History and Clinical Manifestations

Assessment

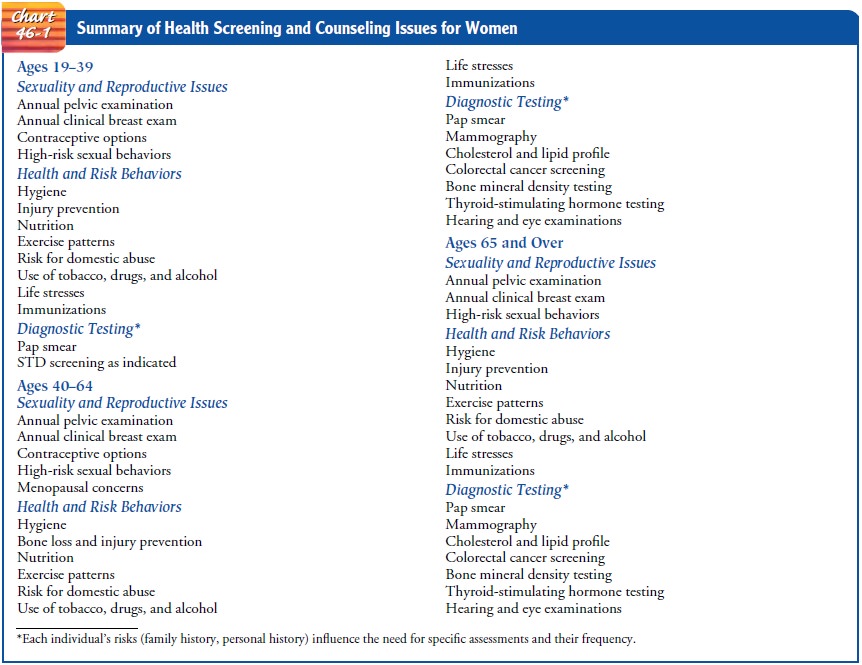

The nurse who is obtaining information from

the patient for the health history and performing physical assessment is in an

ideal po-sition to discuss the woman’s general health issues, health

promo-tion, and health-related concerns. Topics that are relevant would include

fitness, nutrition, cardiovascular risks, health screening, sex-uality, abuse,

health risk behaviors, and immunizations. Recom-mendations for health screening

are summarized in Chart 46-1.

HEALTH

HISTORY AND CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

In

addition to obtaining a general health history, the nurse asks about past

illnesses and experiences that are specific to women’s health. Data should be

collected about the following:

• Menstrual history (including menarche, length of cycles, length and

amount of flow, presence of cramps or pain, bleeding between periods or after

intercourse, bleeding after menopause)

• History of pregnancies (number of pregnancies, outcomes of pregnancies)

• History of exposure to medications (diethylstilbestrol [DES], immunosuppressive

agents, others)

• Pain with menses (dysmenorrhea),

pain with intercourse (dyspareunia),

pelvic pain

• History of vaginal discharge and odor or itching

• History of problems with urinary function (ie, frequency or urgency); may be related

to STDs or pregnancy

• History of problems with bowel or bladder control

• Sexual history

• History of sexual abuse or physical abuse

• History of surgery or other procedures on reproductive tract structures (including

female genital mutilation or female circumcision)

• History of chronic illness or disability

that may affect health status, reproductive health, need for health screening,

oraccess to health care

• History of genetic disorder

In collecting data related to reproductive health, the nurse is in a unique position to teach patients about normal physiologic processes, such as menstruation and menopause, and to assess possible abnormalities. Many problems experienced by young or middle-aged women can be corrected easily. If allowed to go un-treated, however, they may result in anxiety and health problems. Issues related to sexuality and sexual function are typically brought more often to the attention of the gynecologic or women’s health care provider than other health care providers; any nurse, how-ever, should consider these issues to be part of routine health assessment.

Sexual History

A

sexual assessment includes both subjective and objective data. Health and

sexual histories, physical examination findings, and laboratory results are all

part of the database. The purpose of a sexual history is to obtain information

that provides a picture of the woman’s sexuality and sexual practices and

promotes sexual health. The sexual history may enable the patient to discuss

sex-ual matters openly and to discuss sexual concerns with an in-formed health

professional. This information can be obtained with the health history after

the gynecologic-obstetric or geni-tourinary history is completed. By

incorporating the sexual his-tory into the general health history, the nurse

can move from areas of lesser sensitivity to areas of greater sensitivity after

estab-lishing initial rapport.

Taking

the sexual history becomes a dynamic process reflecting an exchange of

information between the patient and the nurse and provides the opportunity to

clarify myths and explore areas of con-cern that the patient may not have felt

comfortable discussing in the past. In obtaining a sexual history, the nurse

must not assume the patient’s sexual preference until clarified. When asking

about sex-ual health, the nurse also cannot assume that the patient is married

or unmarried. Asking a woman to label herself as single, married, widowed, or divorced

may be seen as an inappropriate inquiry by the patient. Asking about a partner

or about current meaningful re-lationships may be a less offensive way to

initiate a sexual history.

The

PLISSIT (Permission, Limited Information, Specific Suggestions, Intensive

Therapy) model of sexual assessment and intervention may be used to provide a

framework for nursing in-terventions (Annon, 1976). The assessment begins by

introduc-ing the topic and asking the woman for permission to discuss issues of

sexual functioning with her.

The

nurse can begin by explaining the purpose of obtaining a sexual history (eg, “I

ask all my patients about their sexual health. May I ask you some questions

about this?”). History taking con-tinues by inquiring about present sexual activity

and sexual ori-entation (eg, “Are you currently having sex with a man, a woman,

or both?”). Inquiries about possible sexual dysfunction may in-clude, “Are you

having any problems related to your current sex-ual activity?” Such problems

may be related to medication, life changes, disability, or the onset of

physical or emotional illness. Patients can be asked about their thoughts on

what is causing the current problem.

Limited information about sexual function may be provided to the patient. As the discussion progresses, the nurse may offer specific suggestions for interventions. For some women, a pro-fessional who specializes in sex therapy may provide more inten-sive therapy as needed. By initiating an assessment about sexual concerns, the nurse communicates to the patient that issues about changes in sexual functioning are valid health topics for discus-sion and provides a safe environment for discussing these sensi-tive topics.

Risk

for STDs can be assessed by asking about number of part-ners in the past year

or in the patient’s lifetime. An open-ended question related to the patient’s

need for further information should be included (eg, “Do you have any questions

or concerns about your sexual health?”). Nurses should be aware that some women

and men are using the Internet to seek partners; obtain-ing sexual partners

this way has been associated with an increased risk for STDs (McFarlane, Bull

& Rietmeijer, 2000; U.S. Depart-ment of Health and Human Services, 2001).

Young

women may be apprehensive about irregular periods, may be concerned about STDs,

or may need contraception. They may want information on using tampons,

emergency contracep-tion, or issues related to pregnancy. Perimenopausal women

may have concerns about irregular menses; menopausal women may be concerned

about vaginal dryness and burning with inter-course. Women of any age may have

concerns about sexual satis-faction, orgasm or anorgasmia (lack of orgasm).

Female Genital Mutilation

Female

genital mutilation (FGM) refers to the partial or total re-moval of the

external female genitalia or other injury to female or-gans. Individuals from

some cultures believe that FGM promotes hygiene, protects virginity and family

honor, prevents promiscu-ity, improves female attractiveness and male sexual

pleasure, and enhances fertility. It is viewed in some cultures as a rite of

passage to womanhood. Many organizations (eg, World Health Organi-zation,

Amnesty International) are working to end this practice.

Four

types of FGM are known: excision of the clitoral pre-puce; total excision of

the clitoral prepuce and glans with partial or total excision of the labia

minora; excision of part or all of the external genitalia and stitching or

narrowing of the vaginal open-ing (referred to as infibulation); and

unclassified, which includes pricking, piercing, or incision of the clitoris,

the labia, or both, stretching of the clitoris or surrounding tissues, and

introduction of corrosive substances into the vagina (American College of

Ob-stetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG] Committee Opinion #151, 1995). FGM is usually performed between 4 and

10 years of age; hemorrhage and infection may be consequences.

A

growing number of women entering the U.S. health care system underwent FGM

before coming to this country (Ng, 2000). Others have undergone FGM since they

arrived in the United States. Because FGM can affect sexual function,

men-strual hygiene, and bladder function, the possibility of FGM is included in

the sexual history, particularly for women from cul-tures and countries where

the practice is common.Long-term complications of FGM include urinary problems,

chronic vaginitis and pelvic infections, inability to undergo pelvic

examination, painful intercourse, impaired sexual response, ane-mia, increased

risk for HIV infection due to tearing of scar tissue, and psychological and

psychosexual sequelae (American Medical Association, 1995). Nurses who care for

patients who have under-gone FGM need to be sensitive, empathetic,

knowledgeable, and nonjudgmental.

Domestic Violence

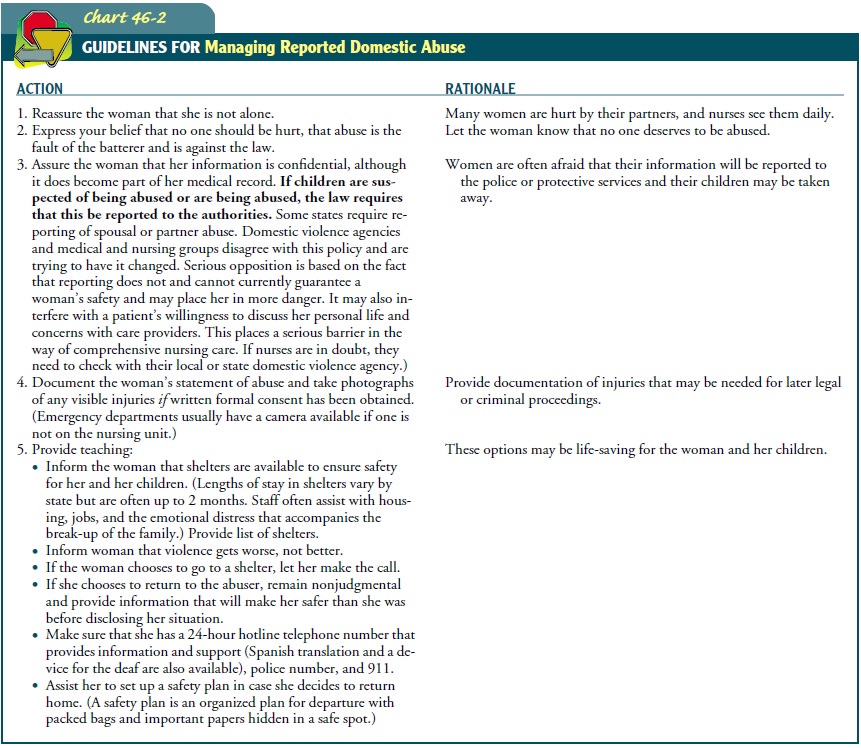

Domestic

violence is a broad term that includes child abuse, elder abuse, and abuse of

women and men. Abuse can be emotional, physical, sexual, or economic. Battering

involves repeated physical or sexual assault in a context of coercive control

and, more broadly, emotional degradation, threats, and intimidation. Nurses

need to be aware of the prevalence of abuse and violence directed against women

in our society. Abuse is related to the need to maintain con-trol of a partner

and involves fear of one partner by another and control by threats,

intimidation, and physical abuse. Violence is rarely a one-time occurrence in a

relationship; it usually continues and escalates in severity. This is an

important point to emphasize when a woman states that her partner has hurt her

but has promised to change. Batterers can change their behavior, but not

without ex-tensive counseling and motivation. If a woman states that she is

being hurt, sensitive care is required (Chart 46-2). Because more than 6

million women experience domestic violence each year, battered women are

encountered daily in nursing practice. By knowing about this major public

health problem, being alert to abuse-related problems, and learning how to

elicit information from women about abuse in their lives, nurses can offer inter-vention

for a problem that might otherwise go undetected. Asking each woman about

violence in her life in a safe environment (ie, a private room with the door

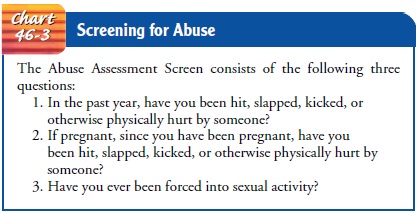

closed) is part of a comprehensive as-sessment and universal screening. The

Abuse Assessment Screen has been found effective in identifying the presence of

abuse and should be included in the health history of all women (Chart 46-3).

No specific signs or symptoms are diagnostic of battering; however, nurses may see an injury that does not fit the account of how it happened (eg, a bruise on the side of the upper arm after “I walked into a door”). Manifestations of abuse may involve sui-cide attempts, drug and alcohol abuse, frequent emergency department visits, vague pelvic pain, and depression. However, there may be no obvious signs or symptoms.

Women in abusive situations often report that they do not

feel well, due to the stress of fear and anticipation of abuse. Nurses need to

be knowledge-able about abuse, ask every woman patient about abuse in her life,

provide resources, and follow written protocols within their in-stitution to

ensure comprehensive care.

Incest and Childhood Sexual Abuse

Because

more than one in five women has experienced incest or childhood sexual abuse,

nurses frequently encounter women who have been sexually traumatized. It has

been reported that female survivors of sexual abuse have more health problems

and undergo more surgery than women who were not victimized. Victims of childhood

sexual abuse are reported to experience more chronic de-pression, posttraumatic

stress disorder, morbid obesity, marital in-stability, gastrointestinal

problems, and headaches, as well as greater use of health care services, than

persons who were not vic-tims. Chronic pelvic pain in women is often associated

with phys-ical violence, emotional neglect, and sexual abuse in childhood (ACOG

Educational Bulletin #259, 2001). Women who

have ex-perienced rape or sexual abuse may have difficulty with pelvic

ex-aminations, labor, pelvic or breast irradiation, or any treatment or

examination that involves hands-on treatment or requires removal of clothing.

Nurses should be prepared to offer support and refer-ral to psychologists,

community resources, and self-help groups.

Rape and Sexual Assault

Sexual

assault occurs every 6 minutes in the United States. Men, women, and children

may be victims. Sexual assault nurse exam-iners, emergency department staff,

and gynecologists perform the painstaking collection of forensic evidence that

is needed for criminal prosecution. Oral, anal, and genital tissue is examined

for evidence of trauma, semen, or infection. Saliva, hair, and fin-gernail

evidence is also collected. Cultures are obtained for STDs, and prophylactic

antibiotics are prescribed. HIV testing is offered and is repeated in 3 to 6

months. HIV prophylaxis is not univer-sally recommended but is considered when

mucosal exposure to contamination has occurred. Prophylaxis against chlamydia

and gonorrhea are provided (Kaplan, Feinstein, Fisher et al., 2001). Emergency

contraception is provided if requested. Emotional counseling is provided, and

follow-up treatment visits are arranged. Rape trauma syndrome is the emotional

reaction to a sexual as-sault and may consist of shock, sleep disturbances,

nightmares, flashbacks, anxiety, anger, mood swings, and depression. It is

im-portant for survivors to discuss the experience and to obtain pro-fessional

counseling.

Screening

for abuse, rape, and violence should be part of routine assessment because

women often do not report or seek treatmentfor assault. Often, the assailant is

a partner, husband, or date. Nurses may encounter women with infections or

pregnancies re-lated to sexual assault that were never treated.

Health Issues of Women With Disabilities

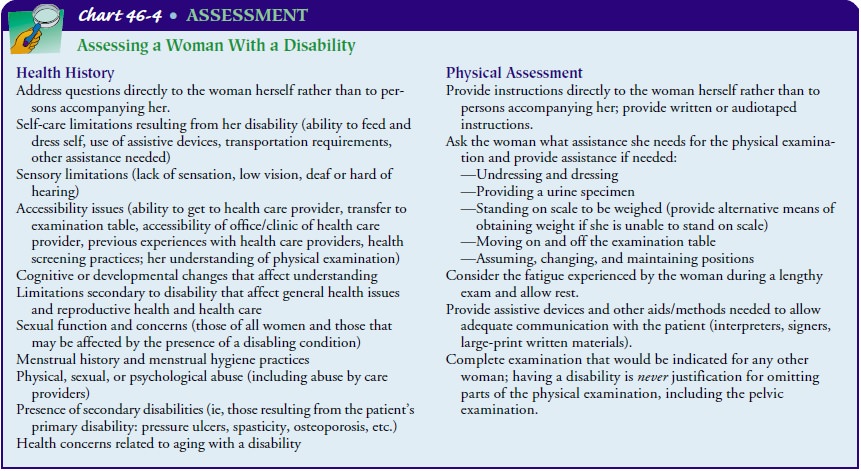

Studies have shown that women with

disabilities receive less primary health care and preventive health screening

than other women, often because of access problems and health care providers’

focus on the causes of disability rather than on general health issues of

concern to all women. To address these issues, the history should include

questions about barriers to health care experienced by dis-abled women and the

effect of their disability on their health sta-tus and health care. Other

issues to be addressed are identified in Chart 46-4. If the patient has hearing

loss, vision loss, or another disability, the nurse may need to obtain the

assistance of a signer or interpreter. The nurse assessing a person with a

disability may re-quire additional time and the assistance of others to be

certain that accurate information is obtained from the patient. Extra time may

be needed to conduct the assessment in a sensitive and unhurried manner

(Kirschner, Gill, Reis & Welner, 1998; Smeltzer, 2000).

Related Topics