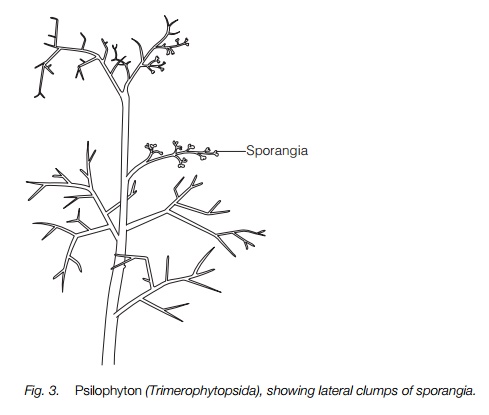

Chapter: Plant Biology : Spore bearing vascular plants

Early evolution, Origins and Life cycle of vascular plants

EARLY EVOLUTION OF VASCULAR PLANTS

Key Notes

The earliest vascular Plants

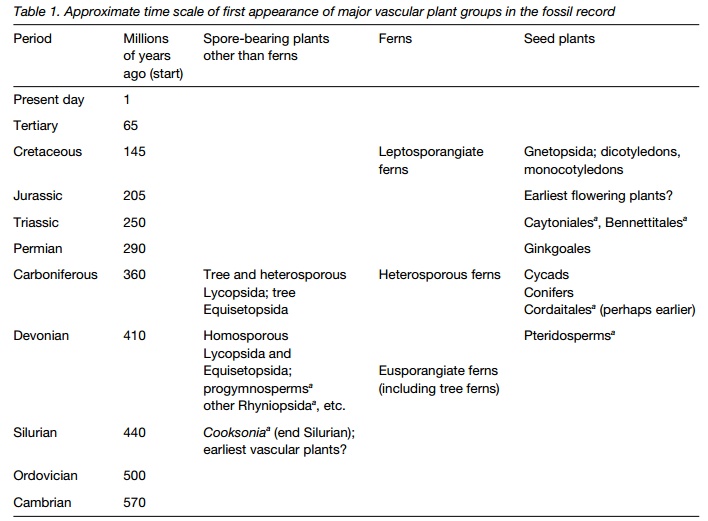

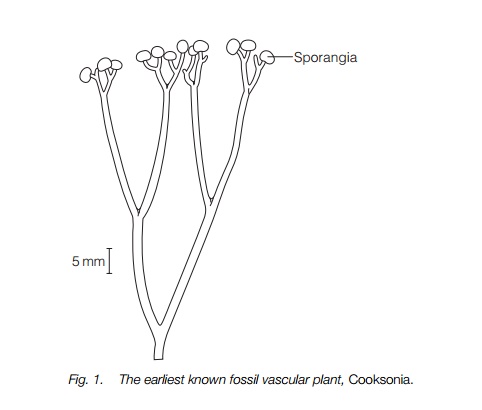

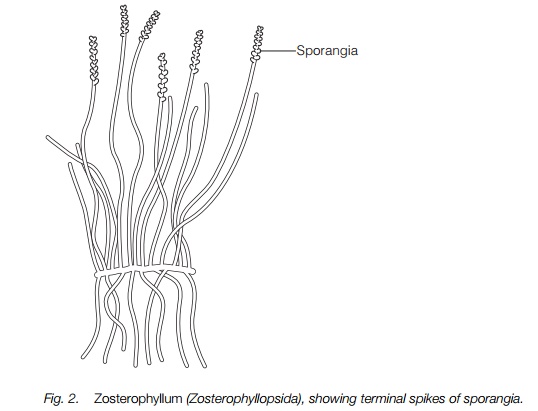

Earliest fossils of vascular plants, Cooksonia, occur in late Silurian rocks. It had photosynthetic stems but no leaves or roots; only rhizoids anchored to soil. Cooksonia had no stomata. By the early Devonian period, several genera are known. They were low growing plants less than 50 cm high bearing sporangia at the tips (Rhyniopsida), laterally (Zosterophyllopsida) or in bunches (Trimerophytopsida).

Life cycle

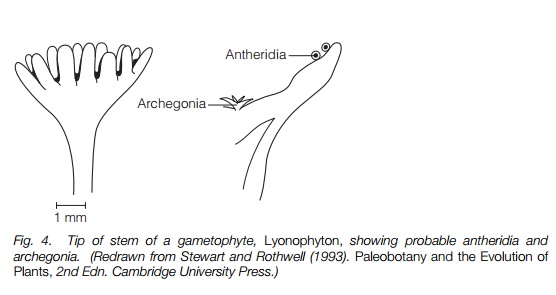

Most were probably homosporous. Gametophytes are little known, but some probable gametophyte fossils resemble the sporophytes with cuplike structures at the tips bearing archegonia and antheridia

Later developments

There was rapid diversification through the Devonian era with developments of monopodial branching and trees belonging to the ferns and other living groups.

Origins and Evolution

Compared with an aquatic environment, land plants need to withstand changes in temperature and humidity, wind, rain and desiccation. They need a conducting system for water and nutrients, and mechanical strength. Reproduction must be possible in the air or on a damp soil surface. Most of them probably formed swards a few centimeters high.

The earliest vascular plants

Vascular plants probably first appeared in the Silurian era (Table 1). The oldest fossils are those of Cooksonia (Fig. 1) in the Rhyniopsida from late Silurian rocks, a little over 400 million years old. Fossils of Cooksonia have been found in several places in Europe and North America. These plants had photosynthetic stems up to about 10 cm high that branched dichotomously, i.e. into two even branches at each point, but no leaves or roots. Some had rhizomes, horizontal underground stems, and subterranean rhizoids, short outgrowths from the rhizomes or stems one cell thick, that may have absorbed water and anchored the plant. The earliest Cooksonia fossil species had no stomata and had a simple vascular system with tracheids. The carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere was higher than at present and these plants may have obtained sufficient carbon dioxide through diffusion into its stems, or may have absorbed it from the ground through its rhizoids, like living quillworts . They had sporangia at the branch tips.

At the beginning of the Devonian period, about 395 million years ago, a slightly more complex fossil plant, Zosterophyllum (Fig. 2) is found. In slightly younger rocks several genera are known, the most famous being the beautifully preserved fossils in siliceous cherts from Rhynie in Scotland, from which the group name, Rhyniopsida, derives (Table 1). Rocks of a similar age from several places, mainly in Europe, have fossils of these and related plants. These plants were more varied and complex, though Rhynia itself resembled Cooksonia in many ways. All the later plants did have stomata and the potential for gas exchange in the stems. The attachment of these plants to the ground was by means of horizontal or arching rhizomes or a swollen corm-like section of the stem; thin, thread-like rhizoids grew out from these to penetrate the substrate and absorb water and nutrients.

Zosterophyllum had lateral sporangia and some members of the Zosterophyllopsida had spine-like outgrowths of the stem resembling tiny leaves, but without any vascular connection with the stem. A third group, the Trimerophytopsida (Fig. 3), had a single main branch with side branches, i.e. were monopodial, with sporangia in terminal bunches.

Life cycle

Most of the fossil remains of these early vascular plants are of sporophyte plants. There appear to have been no dehiscence mechanisms in the sporangia of Cooksonia and some others, though some plants had epidermal cells aligned in spirals, possibly associated with dehiscence. As far as is known most of these plants were homosporous, i.e. producing just one type of spore. In living homosporous plants the spores germinate and grow into a gametophyte bearing male and female gametes. A few Devonian Zosterophyllopsida bore two sizes of spores and these plants could have beenheterosporous. Living heterosporous plants bear spores that develop into gametophytes with either male gametes or female gametes but not both. Male gametophytes normally derive from smaller spores than female gametophytes. There is no evidence apart from this for heterospory in these plant groups.

Gametophytes from these plants are not well known, but some plants that were probably gametophytes were upright, branched structures resembling a sporophyte. Structures resembling archegonia and antheridia were borne in cup-like structures on the tops of the stems, some of which were lobed (Fig. 4). It is likely that rain splashes dispersed the sperm, perhaps often to neighboring archegonia effecting self-fertilization. In many ways the fertile cup-shaped structures must have resembled the ‘inflorescences’ of some mosses in habit and function. It also suggests that in some, at least, of these early plants, the alternation of generations may have been isomorphic, i.e. between a sporophyte and a gametophyte that resembled each other, as in some algae. If other gametophytes were small and growing on the soil surface, as in living relatives of these plants, it is likely that preservation will be poor. The early evolution of gametophytes remains unknown

Later developments

Increasing numbers of fossil plants appear in rocks of the Devonian era, 410–360 million years ago, suggesting that land plants diversified rapidly during this period (Table 1). These fossils include many short herbaceous species like those already described, and some shrubby ones with elaborate rhizome systems. Plants became taller, with monopodial branching and, by the end of the Devonian there were many trees. These mainly belonged to groups with living members, the Lycopsida, Equisetopsida and Polypodiopsida (ferns).

Origins and evolution

Vascular plants have many similarities with green algae (Chlorophyta;), and probably evolved from them. The land provides a different and harsher environment compared with the aquatic or semi-aquatic environment that the algae occupied. Plants on land must be able to withstand large changes in temperature and humidity, wind and rain, and have some means of withstanding desiccation. They need a conducting system throughout the plant for water and nutrients, some structure in the ground to anchor and absorb water and a mechanically strong body. They also need reproductive structures that do not require water. Add to this the fact that the organic component in soils, vital for its nutrient cycling, must have been limited in development with so few land-living organisms.

Land plants are adapted to a low sodium environment and osmoregulate using potassium (K+), sodium being toxic . Their evolution from marine organisms would require major changes in ion transporters at the cellular level. It is possible that they colonized the land via brackish or fresh water.

Many of the problems mentioned above are eased by small size, and the earliest land plants were no more than about 50 cm high. On the soil surface the environment will be fairly wet, at least after rain, and some aspects of the lives of these plants, particularly sexual reproduction, probably took place there. Sexual reproduction involves motile sperms which need a damp substrate for the sperms to swim in; modern ferns and other spore-bearing plants still have this requirement for sexual reproduction. There is some evidence that these plants mainly occurred in wet environments, perhaps forming swards about 10–20 cm high.

Related Topics