Chapter: Plant Biology : Spore bearing vascular plants

The ferns

THE FERNS

Key Notes

General characteristics

Ferns are a large group of plants occurring throughout the world. Most have rhizomes with roots and some have a trunk. Leaves are typically large and pinnate derived from a branch system. A few ferns have a eusporangium similar to those of other spore-bearing plants, but most have a leptosporangium with explosive dehiscence, dispersing the spores. They are homosporous except for one small group.

Eusporangiate ferns

Three small groups, the adderstongues, Marattiaceae and whisk-ferns, are eusporangiate. Adderstongues are small, do not resemble typical ferns and usually have two branches, one bearing the large sporangia. Marattiaceae resemble typical ferns except in the sporangia. Whisk-ferns have no roots or leaves and resemble the earliest vascular plants.

Typical leptosporangiate ferns

These have a stem, usually a rhizome, and roots with no secondary thickening. Leaves are often large and pinnate but may be simple or one cell thick. Sporangia are borne in sori on the underside of leaves or on reproductive leaves separate from the vegetative leaves.

Water ferns

Two small groups of ferns are aquatic, the Marsileaceae on mud and Salviniaceae that float. They are small heterosporous plants and do not resemble typical ferns. Sporangia are on separate branches and do not dehisce. Megasporangia usually contain one spore.

The gametophyte

Typical ferns have a green prothallus 1 cm across on damp soil, bearing antheridia and archegonia on its underside. It has rhizoids. Eusporangiate ferns have larger longer-lived prothalli, some being subterranean. The heterosporous ferns have much reduced gametophytes retained within the spore wall.

Ecology of ferns

Though often common they do not dominate, except for bracken. They are mainly found in dense shade in woods or rocky crevices and as pioneers of gaps in rainforest and as epiphytes. Bracken can cover moorland through vegetative growth.

Fossil ferns

Many fossils are known from the mid-Devonian period onwards. They resemble modern ferns, and tree ferns are common in coal. Only eusporangiate ferns are known until the Cretaceous period. Heterospory is known from the Carboniferous period onwards.

Ferns and man

Bracken was formerly used as bedding and kindling, and young shoots of ferns are eaten, although some are carcinogenic. The main use now is ornamental.

General characteristics

The ferns are a numerous and important group of vascular plants, with about 12 000 species growing throughout the world. They range from small epiphytes to tree ferns 20 m high to floating aquatics. Many ferns have a perennial rhizome, either underground or growing along a branch if epiphytic, with roots attached. Characteristically, ferns have large pinnate leaves, i.e. with numerous leaflets, but some have simple leaves and there is a great range in size. The leaves are regarded as flattened and fused branch systems that have become determinate in their growth, i.e. without stem buds, so they cannot continue growing (a few climbing ferns have stem buds in their leaves and these are indeterminate in their growth). This type of leaf has a fundamentally different origin from the microphylls of clubmosses and horsetails and they are known as megaphylls . The conducting system is typical of vascular plants , with the xylem cells being only tracheids except in bracken and some of the water ferns in which there are vessels, perhaps independently evolved from those of flowering plants but almost identical in structure.

The ferns are divided into two main groups based on their sporangia. One group has sporangia similar to those of the clubmosses and horsetails , known as eusporangia. In these, several initial cells form the sporangium and this develops a wall several cells thick. One or more of the cell layers disintegrates to form nutritive tissue for the developing spores. There is a line of weaker cells in the wall which splits to allow spores to be dispersed in the wind.

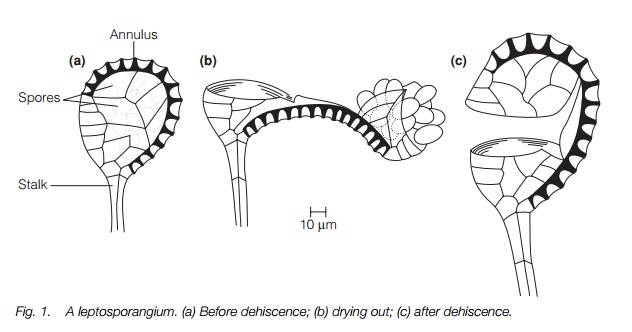

The second type, the leptosporangium, is peculiar to the ferns (Fig. 1). It arises from a single initial cell and the mature sporangium always has a wall one cell thick, all other cells disintegrating as the spores mature. The number of spores is always less than in a typical eusporangium, normally 64 or fewer. There is an incomplete ring of cells in the sporangial wall which has a thin cell wall on the outside and thickened inner walls. On drying out at maturity, the thin sections of the cell wall are sucked in and the thickened walls drawn towards each other. This leads to a split in the part of the sporangial wall not covered by the ring of cells and the ring becoming inverted. Considerable tension builds up which eventually leads to a loss of cohesion in the water molecules in the cell; the water then becomes gaseous leading to a sudden release of tension and an explosive return of the sporangium to its original position. Spores are ejected in

the process. The ring of thick-walled cells is at one end of the sporangial wall in some ferns, in others obliquely or transversely positioned. A few ferns, such as the royal ferns, are intermediate between eusporangiate and leptosporangiate types.

All eusporangiate and most leptosporangiate ferns are homosporous but two small groups of leptosporangiate ferns are heterosporous.

Eusporangiate ferns

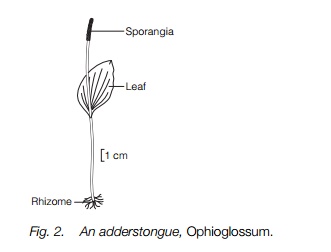

There are three small groups of eusporangiate ferns: the adderstongues and moonworts, the tropical Marattiaceae and the whisk-fern, Psilotum, and its relatives. The adderstongue group consists of small, rather insignificant, plants that do not resemble normal ferns but have one vegetative and one fertile leaf (occasionally more), possibly the remains of a dichotomously branching stem (Fig. 2). The large eusporangia are borne in lines on the fertile leaf, each dehiscing with a slit at the tip to produce 2000 or more spores. They are regarded as a remnant of an ancient group of ferns and one of their most peculiar features is the large number of chromosomes, presumably derived from high polyploidy. One species of adderstongue,Ophioglossum reticulatum, has approximately 1260 chromosomes, the largest number known for any living organism. The Marattiaceae closely resemble typical ferns in their large pinnate leaves with sporangia on the lower surface. The sporangia are typical eusporangia, large with numerous spores and dehiscing by a slit at the tip.

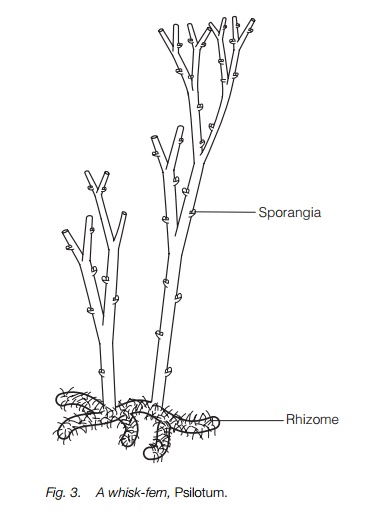

The whisk-fern group consists of two genera, Psilotum (Fig. 3) and Tmesipteris, of such simple vegetative construction that they resemble fossils of some of the first vascular land plants , and were long thought to be related to them, though with no intermediate fossil record. They are regarded as ferns owing to their resemblance to some southern hemisphere ferns. They have branched stems, dichotomous in Psilotum and with flattened side branches in Tmesipteris, a branched rhizome but no leaves or roots. The sporangia are large and, in Psilotum, three are fused together at each point, associated with a small scale.

Typical leptosporangiate ferns

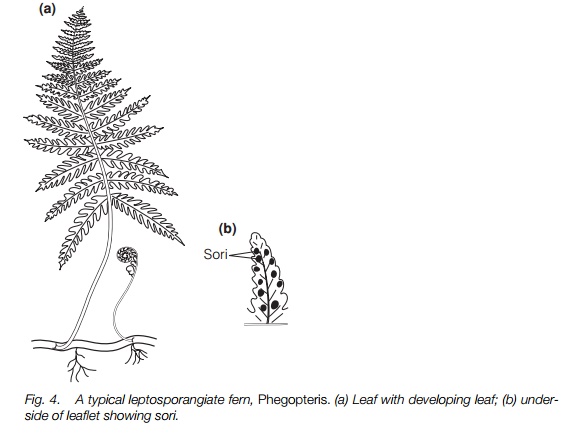

Typical ferns are leptosporangiate and homosporous and are by far the largest and most familiar group of ferns (Fig. 4). The stem is usually an underground or epiphytic rhizome and most produce leaves only at their tip. A few have a branching rhizome, like bracken and, in tree ferns, the stem is a trunk. This trunk has no secondary thickening and often is of a similar width throughout its length, although they frequently have dead roots near the base of the trunk forming a ‘skirt’. Many fern leaves are large and pinnate but others are simple, as in the British hartstongue and the tropical birdsnest fern (both Asplenium) and some tropical climbing ferns have branched leaves of indeterminate growth. In the filmy ferns, Hymenophyllum, the leaf is one cell thick, as in mosses. Simple leaves are regarded as derived from pinnate leaves. Fern leaves unfurl from a tight spiral giving the characteristic ‘fiddle’ heads (Fig. 4).

In many ferns, all leaves are similar and these may bear sporangia, usually on the underside in groups known as sori (singular sorus) (Fig. 4) that, in some species, are covered by a protective flap from the leaf, the indusium. Some ferns have separate fertile leaves of a different shape, usually with narrower segments and sometimes with the lamina much reduced.

Water ferns

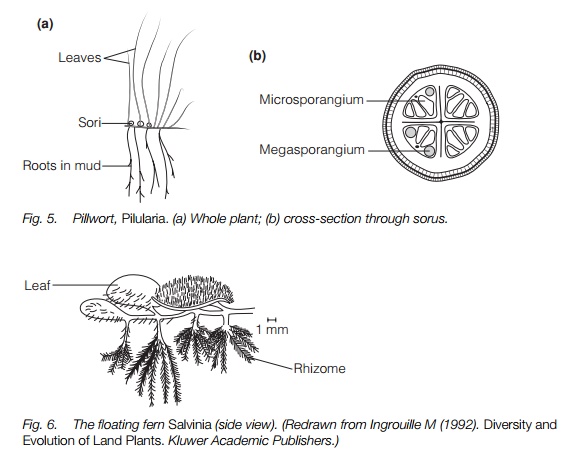

The aquatic ferns do not resemble typical ferns and are the only heterosporous ferns. Members of one of the two families, the Marsileaceae, have a rhizomesubmerged or in mud and aerial leaves a few centimeters high resembling clover with two or four leaves, or grass. The sporangia derive from one cell, so are leptosporangiate but have no specialized dispersal. They are borne on separate short stems in a hard oblong or spherical body a few millimeters long covered with rough hairs, the ‘pills’ of the pillwort (Pilularia; Fig. 5). They produce sori inside these, each sorus bearing both megasporangia and microsporangia. Only one spore matures in each megasporangium. Spores are released into water.

The two genera of floating water ferns are not attached to a substrate and both spread vegetatively in a similar way to other floating flowering plants. Salvinia (Fig. 6) has whorls of three simple leaves 3–10 mm long on each rhizome and no roots. Azolla has a tiny two-lobed leaf, with a cavity in the lower lobe containing a cyanobacterium that fixes nitrogen and roots trailing into the water from the nodes. Megasporangia and microsporangia are produced separately on the undersides of the leaves and spores released are into the water. In Azolla there is one megaspore per sporangium, butSalvinia has more than one.

The gametophyte

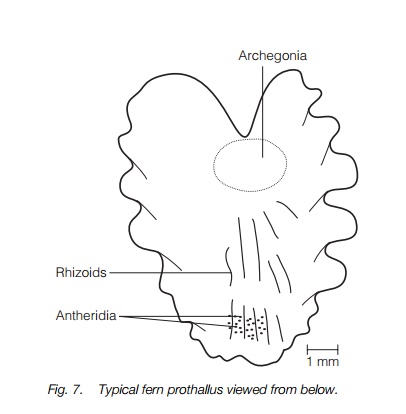

In typical ferns, the gametophyte is a prothallus that is most commonly a small green heart-shaped structure up to about 1 cm across that lives on the surface of damp soil (Fig. 7), sometimes in dense patches. The body of the prothallus consists of undifferentiated parenchyma cells with a thickened central part bearing rhizoids that absorb water. Antheridia and archegonia are produced on the underside. The antheridium is a rounded jacket containing 16–32 motile sperm. The archegonia are produced mainly near the notch, slightly later than the antheridia. Each archegonium has a neck of several cells surrounding two canal cells that degenerate at maturity, and an egg cell at their base, similar to those of bryophytes .

The eusporangiate ferns and royal ferns have larger and longer-lived prothalli than typical ferns and all have fungi associated with them acting as mycorrhizae ; some are colorless and subterranean. The heterosporous water ferns have much reduced gametophytes that develop within the spore wall, as in heterosporous lycopods . They develop in similar ways to Selaginella, although they are unrelated. In the floating group, the microspores aggregate together and hooked hairs develop that may aid attachment to the megasporangia.

Ecology of ferns

Although often common, ferns rarely dominate the vegetation. They mainly frequent damp places since most are limited in their distribution by the need for damp ground for spore germination and gametophyte growth. The enormous numbers and wide distribution of spores makes them good colonizers of suitable sites and many are pioneers, quick to exploit gaps. They are frequently found in shady situations under dense tree canopy or in rocky crevices. In the tropics, many ferns are epiphytic and they can be among the commonest epiphytes in drier parts of the rainforest; epiphytic ferns include the birdsnest fern which can grow to 3 m across. Several species, such as bracken, Pteridium aquilinum, spread vegetatively with branching rhizomes. These can spread tocover large areas, usually where the soil has eroded or degraded as a result ofcultivation or forest clearance, and often well away from damp ground. Brackenis one of the world’s most common plants, sometimes covering areas of moorland,and in places is considered a serious plant pest.

Very few animals eat ferns although there are a number of specialist insect feeders. Grazing animals may eat developing shoots. Some ferns contain high concentrations of insect molting hormone which may make them toxic.

Fossil ferns

Fossils of ferns are numerous from the mid-Devonian period onwards. They were important in the coal measures of the Carboniferous period. There were many tree ferns and non-woody species with various branching patterns. The fossils provide evidence, mainly from leaf form, that ferns probably evolved from the Trimerophytopsida . Sporangia of all the early ferns were eusporangiate. True leptosporangia, as seen in most modern ferns, probably did not appear until the Cretaceous period ( Table 1). Living leptosporangiate ferns evolved in parallel with the flowering plants in recent epochs.

Several fossil ferns from the mid-Carboniferous period and later were heterosporous. They are not directly related to the living heterosporous water ferns and it is clear that heterospory has evolved several times within the ferns.

Ferns and man

Considering their abundance, our uses of ferns have been limited, although bracken was extensively used for animal bedding and as kindling in Europe. The young developing leaves of bracken and some other ferns have been harvested as food for centuries, sometimes much sought after as a delicacy and still eaten, particularly in the Far East. Unfortunately some are carcinogenic and there is a relationship between regular eating of fern shoots and throat or esophageal cancer.

The main current use for ferns is as ornamentals. Their feathery leaves have long been admired and some rare species have been much sought after, as a result becoming rarer. Leaves are used in flower arrangements as background and orchids and other epiphytes are often grown on pieces of tree fern trunk or in a fibrous soil made from crushed fern leaves.

Related Topics