Chapter: Biology of Disease: Disorders of the Gastrointestinal Tract, Pancreas, Liver and Gall Bladder

Disorders of the Stomach

DISORDERS OF THE STOMACH

Gastritis is the most common disorder affecting the stomach and

is character-ized by inflammation and erosion of the gastric mucosa. Gastritis

is idiopathic in many cases but it can be caused by irritating foods,

beverages, ingested poisons, aspirin and staphylococcal exotoxin . Gastritis

may present acutely where the patient suffers from GIT bleeding, epigastric

pain, that is pain on or over the stomach area, anorexia and hematemesis or

vomit-ing of blood. Patients with chronic gastritis may have no symptoms except

for epigastric pain. The possibility of exposure to irritating substances must

be determined when assessing the patient’s clinical history. Gastroscopy, in

which a tube with a camera on its end is passed into the stomach allowing a

direct visualization of its wall, can be used to confirm the diagnosis by

reveal-ing inflamed portions of the lining of the stomach. Relief from the symptoms

of gastritis occurs following removal of the irritant substance or treatment of

the underlying cause(s).

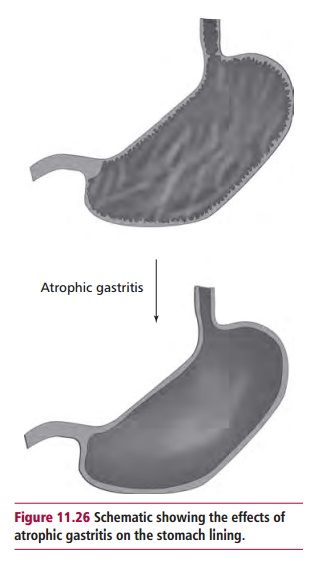

Atrophic gastritis is a degenerative stomach disorder

characterized by chronic inflammation of the stomach with atrophy of its mucous

membrane lining (Figure 11.26). This

results in loss of gastric glandular cells and their eventual replacement by

nonsecretory and fibrous tissues. Secretions of hydrochloric acid, pepsin and

intrinsic factor are impaired, leading to digestive problems, vitamin B12

deficiency and megaloblastic anemia. Atrophic gastritis is the result of

long-term damage to the gastric mucosa and is usually detected late in life. It

can be caused by persistent infection with the bacterium Helicobacterpylori but it can also have an autoimmune origin.

Helicobacter pylori is able to bind to the stomach

lining where the bacteriarelease urease, which hydrolyzes urea, releasing

ammonia that neutralizes the stomach acid. This allows the bacterium to

penetrate into the mucosal layer. The release of bacterial and inflammatory

toxic products by Helicobacter pylori

over time results in increasing gastric mucosal atrophy. Some glandular units

develop an intestinal-type epithelium; others are simply replaced by fibrous

tissue. The loss of gastric mucosa decreases the amount of acid secretion that

increases the gastric pH and leads to a reduced ability to kill bacteria.

Ingested bacteria can survive and reside in the stomach and the upper part of

the small intestine. Infection is usually acquired during childhood and, if

left untreated, progresses over the lifespan of the individual in one of two

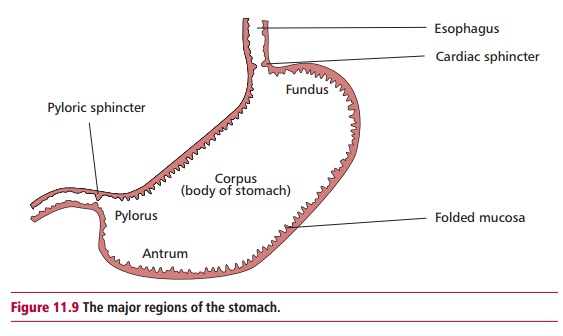

main ways that have different pathological consequences. The first is a

gastritis that mainly affects the antrum of the stomach (Figure 11.9). This is the most frequently observed pattern in

Western countries and individuals with peptic ulcers (seebelow) usually develop this pattern of gastritis. The second

pattern is a morewidespread atrophic gastritis affecting, for example, the

corpus, fundus and antrum with the loss of gastric glands and their partial

replacement by an intestinal-type epithelium. This pattern is observed more

often in developing countries and Asian individuals who develop gastric

carcinoma and gastric ulcers usually present with this pattern of gastritis.

Autoimmune gastritis is associated with serum anti-intrinsic

factor antibodies that reduce the amount of functioning intrinsic factor. This,

in turn, decreases the availability of vitamin B12 and eventually

leads to pernicious anemia in some patients. Cell-mediated immunity also

contributes to the disease because T cell lymphocytes infiltrate the gastric

mucosa and con-tribute to the epithelial cell destruction and resulting gastric

atrophy.

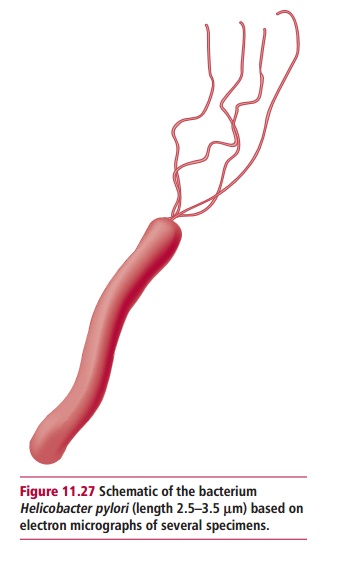

Specific data on the incidence of atrophic gastritis are scarse.

However, its prevalence mimics that of its two main causes. In both types,

atrophic gastri-tis develops over many years and is detected later in life. Helicobacter pylori (Figure 11.27) infects approximately 20%

of people younger than 40 years and 50% of those older than 60 years in the

developed world. Infection is highly prevalent in Asia and in developing

countries and it is estimated that 50% of the world’s population is infected.

Thus chronic gastritis is probably extremely common. In contrast, autoimmune

gastritis is a relatively rare condition, which is most frequently observed in

patients of northern European descent

and in African Americans. The prevalence of pernicious anemia

resulting from autoimmune gastritis is estimated to be 127 in 100 000 in the

UK.

Chronic gastritis frequently is asymptomatic but can

present as nonspecific abdominal pain. Since gastritis often occurs in severely

ill, hospitalized peo-ple, its symptoms may be eclipsed by other, more severe

symptoms.

Atrophic gastritis cannot be reliably diagnosed by

gastroscopy but requires a microscopic examination of biopsy specimens. Helicobacter pylori infections are

normally diagnosed using serological tests, breath tests or antigen tests of

the feces. Pernicious anemia resulting from autoimmune atrophic gastritis

usually presents in patients approximately 60 years of age.

Treatment of atrophic gastritis is directed at

eliminating the causative agent, to correct complications of the disease and

attempt to revert the atrophic process. When Helicobacter pylori is the causative agent, it can be eradi-cated

using a combination of antimicrobial agents and antisecretory agents with a

success rate of about 90%. Lack of patient compliance and antimi-crobial

resistance are the most important factors influencing poor outcome. However,

treatment of Helicobacter pylori

infection may not lead to a reversal of existing damage unless started early

but may block further progression of the disease. Some evidence suggests that A-carotene and/or vitamins C and E

may reverse or reduce the risk of atrophic gastritis and/or gastric cancer. The

major complication in patients with autoimmune atrophic gastritis is the

development of pernicious anemia. This requires vitamin B12 replacement

therapy.

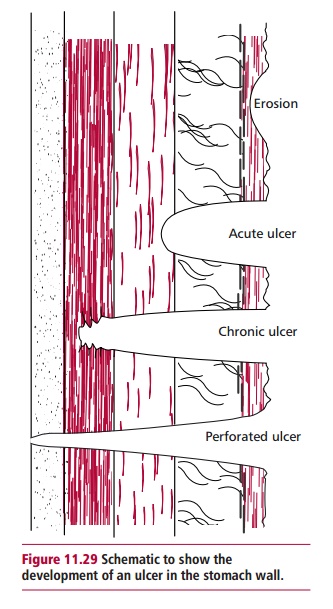

Ulcers are perforations of the GIT wall (Figure 11.28), particularly erosions of

the mucosal layer related to cancer, that is, malignant ulcers, or to stomach

acid, that is, peptic ulcers. Ulcers may also be named from their location, for

example esophageal, gastric or stomach and duodenal ulcers. Esophageal ulcers

are usually associated with hiatus hernias (see

below) caused by acid splashing from the stomach into the lower esophagus.

Gastric ulcers are rela-tively rare because the mucosal lining of the stomach

is protected from the acid by a layer of alkaline mucus. They generally occur

in patients older than 50 years of age. Duodenal ulcers are five times more

common than gastric ulcers and generally occur in a younger population. More than

90% of ulcers occur in the duodenal wall, usually after it has been weakened by

infection with Helicobacter pylori.

It used to be thought that ulcers were caused by stress and excessive

accumulation of HCl. However, it is now accepted that their commonest cause is

infection with Helicobacter pylori (Figure 11.27) which can colonize and

destroy the mucosal layer.

Peptic ulcers are linked to an increased production

of acid and pepsin in gastric juice or to a reduced protection of the mucosa

against gastric juice. Figure 11.29 illustrates

diagrammatically the development of a peptic ulcer.Lesions that do not extend through

the mucosal lining are referred to as ero-sions. Acute and chronic ulcers

penetrate this layer and, in serious cases, may penetrate the stomach wall. In

some patients, blood vessels in the GIT wall ulcerate and lead to heavy, and in

some cases fatal, bleeding. Chronic ulcers have an associated basal scarring.

Patients with peptic ulcers present with epigastric

pain but their diagnosis is made on clinical grounds, supported by endoscopy,

laboratory tests for assessing acid and pepsin secretion and identification of Helicobacter pylori infection. Treatment is aimed at eradication of

the Helicobacter pylori infec-tion

and reducing acid output. Antibiotics that effectively sup-press symptoms

include amoxycillin, clarithromycin, metronidazole and tetracycline, and they

often cure the patient. Bismuth chelate and sucralphate may also be

administered to decrease the synthesis of prostaglandins that stimulate

inflammation. The resulting decrease in acid production by parietal cells and

the increase in hydrogen carbonate production by mucus secreting epithelial

cells have cytoprotective effects.

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome is a rare disorder that

causes massive, multiple and recurrent peptic ulcers due to the excessive

secretion of gastric juice from tumors affecting the pancreas or duodenum.

Approximately 60% of the tumors are malignant. They are called gastrinomas

because they secrete large amounts of gastrin, hence patients have an increased

plasma gastrin concen-tration and rates of gastric acid secretion greater than

100 compared with nor-mal rates of less than 5 mmol h–1.

A diagnosis of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome usually

requires demonstrating an increase in the concentration of gastrin in the

patient’s serum, combined with an increased release of acid in the stomach.

However, in about 30% of cases the plasma gastrin concentration is normal or

only slightly above normal. The pentagastrin test is used to assess the acid

output of the stomach. Pentagastrin is an analog of gastrin that stimulates the

release of stomach acid. Acid output is assessed before and after intramuscular

injection of pentagastrin. Patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome have a high

basal acid output and pentagas-trin causes little further increase. Treatment

of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome is by surgical removal of the gastrinoma.

A hernia

is the protrusion of an organ or tissue out of the body cavity in which it is

normally found. A hiatus hernia occurs when the upper part of the stom-ach is

dislocated through the hole, called a hiatus, in the diaphragm, into the chest.

Sliding hiatus hernias occur when the esophagus and stomach both move upwards

so that the top end of the stomach protrudes through the gap in the diaphragm

normally occupied by the esophagus (Figure

11.30 (A)) and these constitute

90% of cases. The remaining 10% are rolling hiatus hernias where a portion of

the stomach curls upwards adjacent to the esophagus so that both it and an

upper part of the stomach protrude through the gap (Figure 11.30 (B)). The

causes of hiatus hernias are unknown but they may be due to intra-abdominal

pressure or weakening of the gastroesophageal junc-tion caused by trauma or

loss of muscle tone. Over 50% of individuals with hiatus hernia are

asymptomatic, but when symptoms do occur, they include heartburn, which is

aggravated by reclining, chest pain, dysphagia, belching, pain on swallowing

hot fluids and a feeling of food sticking in the esophagus. Although hiatus

hernia is not usually serious, it can cause inflammation of the lower end of

the esophagus leading to a back flow of gastric juices; this is called reflux esophagitis, and it may cause

bleeding (perhaps anemia) or a stricture. Cancer in a hiatus hernia is very

rare, but there is a slight increased risk of it developing in the inflamed

area.

Data on the incidence of hiatus hernia are few but

the condition increases with age and is particularly common in overweight

middle-aged women and can also occur during pregnancy. The contents of the GIT

are often not clearly visible by X-rays and diagnosis requires confirmation

with a barium meal. This consists of barium sulfate mixed with liquid and is

usually flavored. The barium in the meal lines the inside of the GIT wall and

is visible because barium is opaque to X-rays making this a useful method for

detecting structural abnormalities of the GIT. The presence of a hiatus hernia

can also be investigated by gastroscopy.

The aim of treatment is to alleviate the symptoms.

Losing weight, reduc-ing smoking and coffee and alcohol intakes all help to

relieve symptoms. The patient may be advised to avoid tight or restrictive

clothing. Avoiding food intake before sleep and elevating the head of the bed

help in reducing acid reflux. Medication such as antacids may be prescribed.

Surgery is only used when there is strangulation of the hernia or the symptoms

cannot be controlled.

Related Topics