Chapter: Biology of Disease: Disorders of the Gastrointestinal Tract, Pancreas, Liver and Gall Bladder

Disorders of the Small Intestine

DISORDERS OF THE SMALL INTESTINE

Lactose intolerance is a condition arising from an

inability to express lactase. It is divided into three categories: congenital alactasia,

primary acquired and secondary acquired lactose intolerance. Congenital

alactasia or hypolactasia is an extremely rare condition and affected babies do

not gain weight, are dehydrated and extremely unwell. Human milk is unsuitable

for the baby and breastfeeding is precluded, which can also cause emotional

distress in some mothers. These babies must be fed dairy-based but lactose-free

or lactose-free soya formulae to survive. Primary acquired lactose intolerance

usually occurs following weaning and before the age of six years and is the

normal condi-tion for approximately 70% of the world’s population, the major

exception being northern Europeans. It is particularly common in Asian

communities and amongst blacks of African origin. Secondary acquired lactose

intolerance occurs as a result of damage to the small intestinal mucosa, for

example due to gastroenteritis, cows milk protein intolerance or celiac disease

(see below).

Patients who ingest milk suffer from serious

indigestion, nausea and gas, cramps, bloating and diarrhea because of the

action of GIT bacteria on ingested lactose, the severity varying with the

amount of lactose consumed and the tolerance level of the individual. These

rather diffuse symptoms are often associated with other conditions of the GIT,

such as infections with parasitic helminths and the protozoan Giardia , inflammatory conditions, for

example ulcerative colitis (see below),

hormonal complaints, such as hypo- and hyperthyroidism and cancer of the colon

and rectum . Lactose intolerant patients are able to ingest a variety of milk

products such as cheese, where the lactose has been removed in the whey, and

yoghurt, where it has been fermented to lactate.

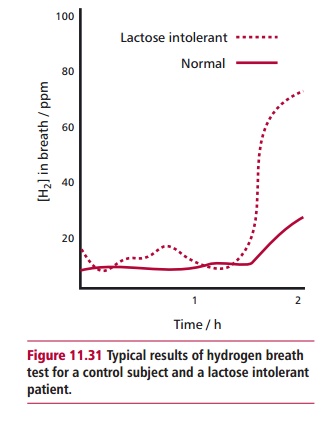

Lactase deficiency can be assessed by the hydrogen breath, stool acidity and lactose tolerance tests. An assay for lactase activity on a tissue sample following a biopsy of the intestinal mucosa would confirm any diagnosis. The hydrogen breath test requires the patient to drink a solution containing 50 g of lactose. If lactase is deficient, the sugar is fermented by colonic bacteria which subsequently produce dihydrogen, some of which will enter the blood and be excreted at the lung surface. Regular analyses of the breath will show the increasing amounts of hydrogen (Figure 11.31) in lactose intolerance. Using the appropriate sugars allows both these tests to be used in diagnosing other disaccharide intolerances, although genetic intolerances to these are rather rare. The principle of the stool acidity test is simple: undigested lactose fermented by bacteria in the colon produces lactate and fatty acids, which can then be detected in a stool sample. The lactose tolerance test is still per- formed but only when other tests are inconclusive since it is more invasive. The patient is required to fast overnight, then drink a solution containing 50 g lactose. Several blood samples are taken over a 2-h period and their glucose concentrations determined. The amount of blood glucose indicates how well the patient is able to digest lactose. The test must be controlled by repeating the procedure using 25 g each of glucose and galactose, the constituent mono-saccharides of lactose.

The medical history, age, degree of intolerance and

overall health of the patient determine treatment for lactose intolerance. In

general, it can be controlled with an appropriate diet. Adding proprietary

products containing lactase (Figure 11.32)

isolated from microorganisms to dairy products prior to ingestion can also help

overcome the problem.

Celiac disease is a genetically determined chronic

inflammatory condition affecting the small intestine and is induced by the

ingestion of wheat pro-tein, specifically gluten, and its products. A portion

of the gluten molecule forms an autoimmune complex in the GIT mucosa which

stimulates T cells to aggregate and release toxins that promote lysis of

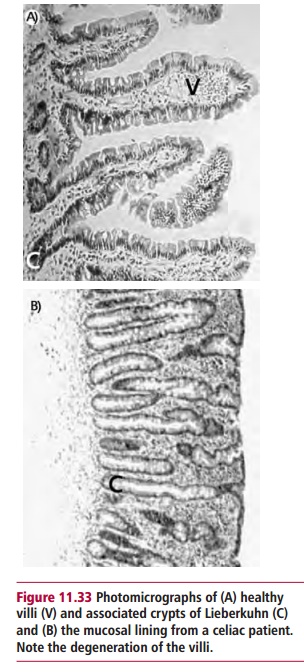

enterocytes. This leads to a progressive atrophy and characteristic flattening

ofthe mucosal villi and microvilli in the upper part of the small intestine (Figure11.33 (A) and (B)). Celiac

disease is a relatively common disorder with aworldwide prevalence of 1 in

200–300. The mucosa improves morphologically when the patient is placed on a

gluten-free diet but relapses occur if gluten is reintroduced in the diet.

Celiac disease is accompanied by malabsorption of nutrients due to a decreased

surface area over which absorption can take place. The signs and symptoms of

celiac disease are surprisingly diverse and include abdominal pain, chronic

diarrhea, weight loss, bone pain, fatigue and anemia. Celiac disease is

diagnosed by demonstrating villous atrophy in a small intestine biopsy (Figure 11.34 (A) and (B)) and by

improvements in clini-cal symptoms or histological tests following restriction

to a gluten-free diet. Gluten-free foods are now readily available in

supermarkets and health food stores. The management of celiac disease involves

adherence to a gluten-free diet, which in most cases helps relieve the symptoms

and allows the existing mucosal damage to heal as well as preventing further

damage.

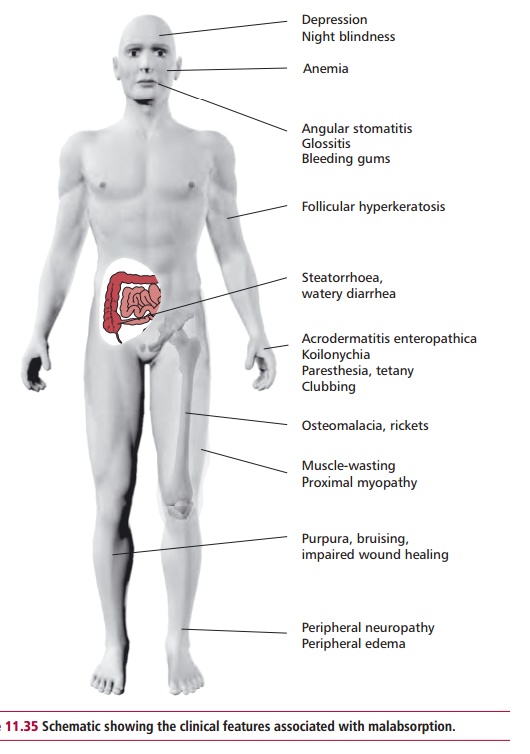

Malabsorption is a reduction in the absorption of one

or more nutrients by the small intestine. It occurs as a result of a wide range

of disorders that affect the GIT, pancreas, liver and gall bladder. Its causes

include enzyme deficiencies, such as in lactose intolerance, chronic

pancreatitis, bile salt deficiency, as in biliary obstruction or hepatitis, and

intestinal diseases such as celiac disease and Crohn’s disease (see below). The clinical features of

malabsorption (Figure11.35) arise

because of deficiency of one or more nutrients and include anemiadue to iron,

folate and vitamin B12 deficiencies, osteomalacia due

to vitamin D deficiency, edema due to hypoalbuminemia, the tendency to bleeding

when vitamin K is suboptimal and generalized weight loss. Malabsorption results

in retention of nutrients in the GIT lumen causing diarrhea and abdominal

dis-comfort due to the action of GIT bacteria. Malabsorption of fats leads to

their losses in amounts greater than 5 g daily and causes steatorrhea. The

feces are greasy, with a pale color and have an offensive smell.

A diseased liver may be unable to synthesize bile

which is required for diges-tion of fats and if absent can lead to

malabsorption. Liver function tests can indicate the presence of liver disease

and a number of blood tests are also use-ful in assessing liver function. These

include determining the concentration of albumin in the plasma and

hematological investigations such as full blood count, iron, vitamin B12 and folate and

can indicate the type of malabsorption. Investigations of malabsorption also

include microbiological examination of feces to identify any pathogens present. The pentose sugar xylose

is absorbed in the small intestine but is not metabolized and is excreted

unchanged in

This property is exploited in the xylose absorption

test to assess the malabsorption of carbohydrates. The patient fasts overnight,

empties the bladder and drinks a 500 cm3 solution containing 5 g

xylose. In normal indi-viduals, the serum xylose concentration increases above

1.3 mmol dm–3 one hour after the test. After 5 h, the concentration

of xylose in the urine increases to more than 7.0 mmol dm–3.

Significantly lower concentrations of xylose occur in the serum of patients

with carbohydrate malabsorption. However, care must be exercised since some

bacteria colonizing the small intestine are capable of metabolizing xylose and

a number of renal diseases can also lead to reduced concentrations.

Malabsorption of fat can occur in a number of pancreatic and

intestinal dis-orders. Bacteria colonizing the small intestine may break down

bile acids, reducing their effective concentration and causing malabsorption. A

fecal fat test can assess fat malabsorption. The test involves collecting feces

over a period of three days after which their fat content is assessed

chemically. Normally, up to 5 g of fat is lost in the feces each day but more

is lost during malabsorption giving rise to steatorrhea.

Crohn’s disease is a chronic inflammation, usually of the ileum,

although it can affect any part of the GIT. The inflammation tends to be patchy

but extends throughout the layers of the intestinal wall thickening the wall

and narrowing the lumen. The cause of Crohn’s disease is unclear although

viruses and bacteria have been implicated. Patients with Crohn’s disease suffer

from lack of appetite, abdominal pain, diarrhea and weight loss. A biopsy of

the GIT is used to detect the characteristic changes associated with Crohn’s

disease. Treatment involves using anti-inflammatory drugs, such

as 5-aminosalicylic acid, although surgery may be required in severe cases.

Related Topics