Chapter: The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology: Chondrichthyes: sharks, skates, rays, and chimaeras

Chimaeras - Subclass Holocephali

Subclass Holocephali

Chimaeras

Although knowledge of holocephalan taxonomy has increased markedly in recent years, surprisingly little remains known about their general biology and natural history . Most of the characters that define the elasmobranchs also describe the Holocephali, indicating a common albeit unknown ancestor. Chimaeras, also known as ratfishes or rabbitfishes, share with sharks a cartilaginous skeleton and male intromittent organs, a sutureless skull, ceratotrichial fins, and spiral valve intestine. Holocephalans similarly lack lungs and gas bladders, also using an oil-filled liver for buoyancy. Development is again direct, without a larval stage (Bigelow & Schroeder 1953a; Compagno 1990b).

In contrast to sharks in which the upper jaw has a ligamentous connection to the cranium (the amphistylic condition), chimaeras have upper jaws that are immovably attached to the braincase (the holostylic condition). The name Holocephali (“whole head”) refers to this fusion of palatoquadrate and neurocranium in modern chimaeras. Teeth differ from those of sharks, being continually growing, crushing or cutting plates instead of replaceable dentition. Chimaeras have three pairs of hypermineralized toothplates, two vomerine and palatine toothplate pairs in the upper jaw and a large pair of mandibular toothplates on the bottom (hence the name rabbitfish). The anterior plates are bladelike, whereas the posterior plates are flattened for crushing hard-bodied foods.

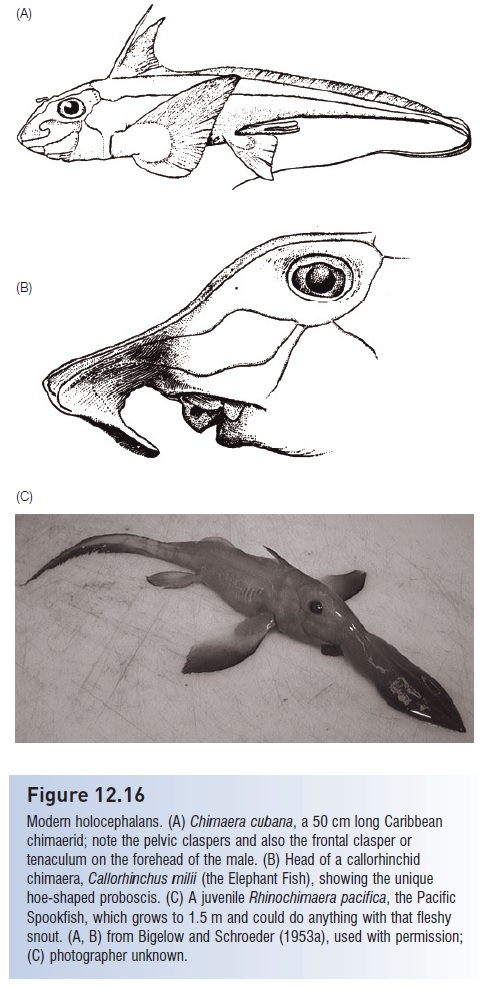

As in bony fishes, a single gill fl ap covers four internal gill openings, rather than the five or more external gill slits of sharks. Chimaeras lack distinct vertebral centra and a spiracular gill opening (embryonic chimaeras have a spiracle). Instead of a cloaca, they possess separate anal and urogenital openings. Males have sharklike pelvic claspers that are extensions of the pelvic fins, through which sperm is transferred. Anterior to the pelvic girdle are prepelvic tenaculae contained in prepelvic pouches. Tenaculae consist of a single row of stout spines and are used to anchor the female during copulation. Males of some species also have an additional frontal tenaculum on the head that is used to grasp the posterior edge of the female’s pectoral fin during copulation (Fig. 12.16). Chimaeras are oviparous, laying a few, 10 cm long eggs with horny shells similar to those of sharks (e.g., Moura et al. 2004); development may take 5–10 months prior to hatching.

Holocephalans lack scales except for small dermal denticles along the midline of the back and on the claspers of the males. The first dorsal fin, with its poison-laden spine, is erectable, not fixed. The body generally tapers posteriorly to a pointed tail, hence the alternative common name ratfish. Chimaeras locomote via a combination of body undulations and pectoral fin fl apping.

Figure 12.16

Modern holocephalans. (A) Chimaera cubana, a 50 cm long Caribbean chimaerid; note the pelvic claspers and also the frontal clasper or tenaculum on the forehead of the male. (B) Head of a callorhinchid chimaera, Callorhinchus milii (the Elephant Fish), showing the unique hoe-shaped proboscis. (C) A juvenile Rhinochimaera pacifica, the Pacific Spookfish, which grows to 1.5 m and could do anything with that fleshy snout. (A, B) from Bigelow and Schroeder (1953a), used with permission; (C) photographer unknown.

Six genera and 33 species of chimaeras are recognized, with perhaps another dozen species remaining to be named.

Adult size ranges from 60 to 200 cm, with females often larger than males. Chimaeras are cool water, marine fishes. Although geographically widespread, low-latitude species occur in deeper water. As a group they are mostly found below 80 m to as much as 2600 m and are usually captured close to the bottom. In contrast to many bony fishes, younger chimaeras often occupy deeper water than adults, the latter partaking in seasonal, inshore migrations (Didier 2005). Chimaeroids feed mostly on hard-bodied benthic invertebrates, which they crush with their toothplates.

Extant holocephalan species represent a small fraction of a previously successful and diverse group. Although only three families in a single order are alive today, 12 fossil orders, represented by perhaps 22 families, lived during Paleozoic and Mesozoic times. Several groups had more sharklike dentition, or dentition unlike any living or other extinct chondrichthyans. The modern families have fossil records dating back to the Jurassic and Cretaceous (Carroll 1988; Nelson 2006).

Related Topics