Chapter: The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology: Living representatives of primitive fishes

Amphioxiforms - Jawless fishes

Amphioxiforms

It can be argued that lancelets are not fishes because they lack many diagnostic characters. However, cephalochordates – which are sometimes referred to as invertebrate chordates along with urochordates and hemichordates – seldom receive treatment in invertebrate textbooks. Their evolutionary and anatomical affinities are much closer to the vertebrates (see Northcutt & Gans 1983; Gans et al. 1996), and lancelets are studied primarily by ichthyologists, providing justifi cation for their inclusion in an ichthyology textbook.

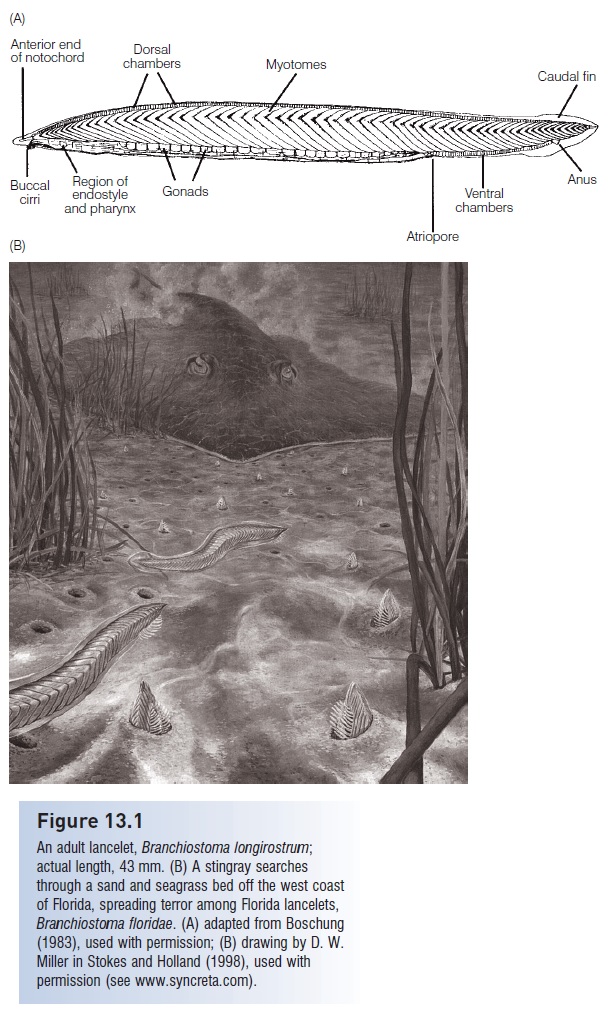

Lancelets are small (up to 8 cm), slender organisms that as adults occupy sandy, usually shallow bottoms in all major oceans (Fig. 13.1). They commonly bury themselves in the sediments with just the anterior portion of the body protruding from the bottom. Lancelets filter diatoms and other small food items from the water via cilia that transport water through the mucus-laden mouth and pharynx and out through the atriopore. Food-trapping mucus is produced by the endostyle, a pharyngeal organ that also functions in iodine uptake and may therefore be homologous to the thyroid of higher vertebrates (Nelson 2006).

Figure 13.1

An adult lancelet, Branchiostoma longirostrum; actual length, 43 mm. (B) A stingray searches through a sand and seagrass bed off the west coast of Florida, spreading terror among Florida lancelets, Branchiostoma floridae. (A) adapted from Boschung (1983), used with permission; (B) drawing by D. W. Miller in Stokes and Holland (1998), used with permission .

Spawning in most species occurs in early summer. Spawning adults swim up into the water column, the females following the males. Larvae metamorphose after 2–5 months. Larvae are free swimming, ciliated, planktonic animals that have the mouth and anus on the left side of the body. The mouth eventually moves to the middle, but the anus remains on the left side. Larvae can be very abundant at times, reaching densities of 1000/m3 in regions of upwelling. The larvae settle on sandy or sandy-shell bottoms, mature in 2 or 3 years, and live as adults for 1–4 years depending on the species. Both larvae and some immature adults undergo diel vertical migrations, moving to surface waters at night (Bigelow & Perez Farfante 1948; Boschung & Shaw 1988).

Lancelets are intriguing in their lack of many typical chordate structures. They differ from conventional fishes by lacking most parts of a head (e.g., there is no cranium, brain, complex eyes, external nostrils, or ears); hence they

Lancelets also lack vertebrae, scales, genital ducts, a heart, red blood cells, hemoglobin, and specialized respiratory structures (gills), and have only one cell layer in the epidermis. Lancelets have up to 25 pairs of gonads as compared to one in lampreys and hagfish and two in most other fishes. The number of internal gill clefts increases throughout life in lancelets, whereas in fishes the number is fixed at birth. The notochord, a definitive chordate structure, extends beyond the anterior end of the dorsal nerve tube (e.g., beyond the “brain”), to the anterior end of the body.

Lancelets are economically valuable in two respects. Branchiostoma lanceolatum, a European and Mediterranean species, is the “amphioxus” commonly used in biology laboratories as a study animal. Besides its utility as an example of primitive chordate features, it is morphologically convergent with the ammocoete larva of the lampreys (see below), thus providing comparative material and popular questions for laboratory practicals. Lancelets are also targeted by a seasonal fishery in southern China, where they are dredged from the bottom with scoops at a rate of about 30,000 kg, or l billion lancelets, annually.

The fossil record for cephalochordates is limited, but recent findings suggest ancestry among the cephalochordate- like yunnanozoans (Haikouella and Yunnanozoon) of the Lower Cambrian, or perhaps in Pikaia from the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale of British Columbia, which had a dorsal nerve cord and notochord (see Jawless fishes). A recognizable cephalochordate fossil has been found in Early Permian deposits in South Africa (Oelofsen & Loock 1981). The evolutionary importance of the lancelets lies in their presumed place as ancestors of advanced chordates, as revealed in their embryology.

Two lancelet families are recognized, each containing one eponymous genus (Branchiostomatidae, Branchiostoma; Epigonichthyidae,Epigonichthyes). A third family, the Amphioxididae, was previously recognized but has since proven to be the larva of aBranchiostoma species that remains planktonic after metamorphosis (Boschung & Shaw 1988). Traditionally, species have been designated on the basis of myomere and fin chamber counts, position of atriopore and anus, gonadal characteristics, and notochord and caudal fin shape. More recently, statistical analysis has revealed considerable meristic variation in such taxonomic features (Poss & Boschung 1996). Additionally, genetic analysis using 12S rRNA gene comparisons and mitochondrial DNA sequences indicates the existence of previously undetected species and lack of monophyly in recognized genera (Nohara et al. 2005; Xu et al. 2005). The coming years will undoubtedly reveal that cephalochordates are richer in biological information and species than has been traditionally held.

Related Topics